TO SCATTER OR SOW: DIASPORA IN CONTEMPORARY ART Curated by Elizabeth Hoy, Beard & Weil Galleries, Watson Fine Arts, Wheaton College, September 7– October 23, 2021

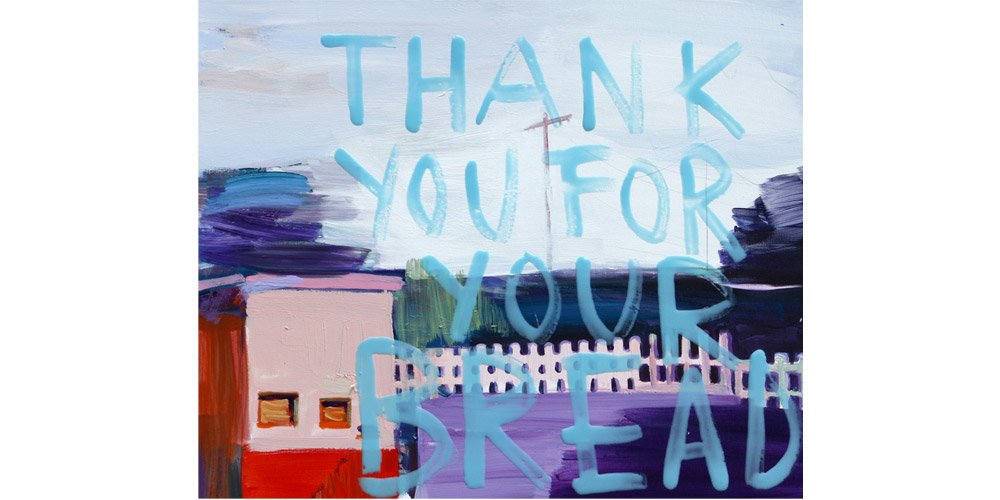

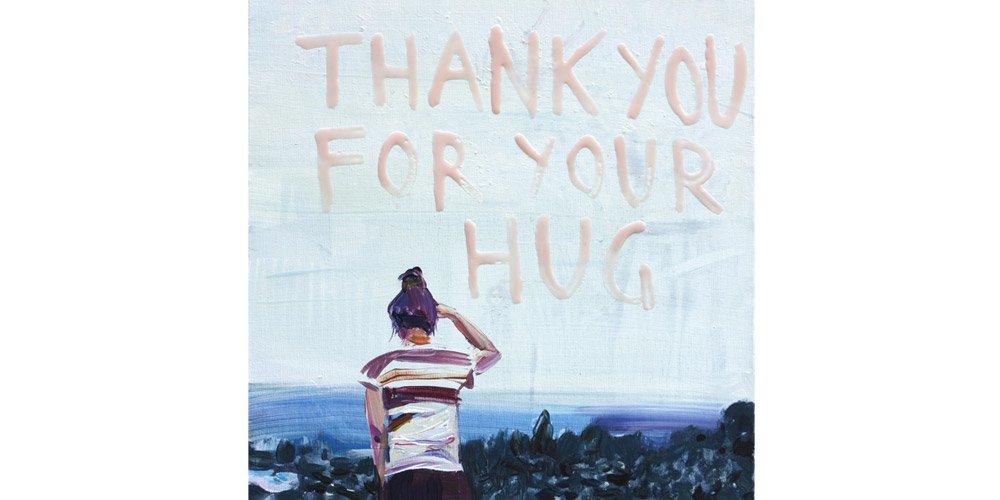

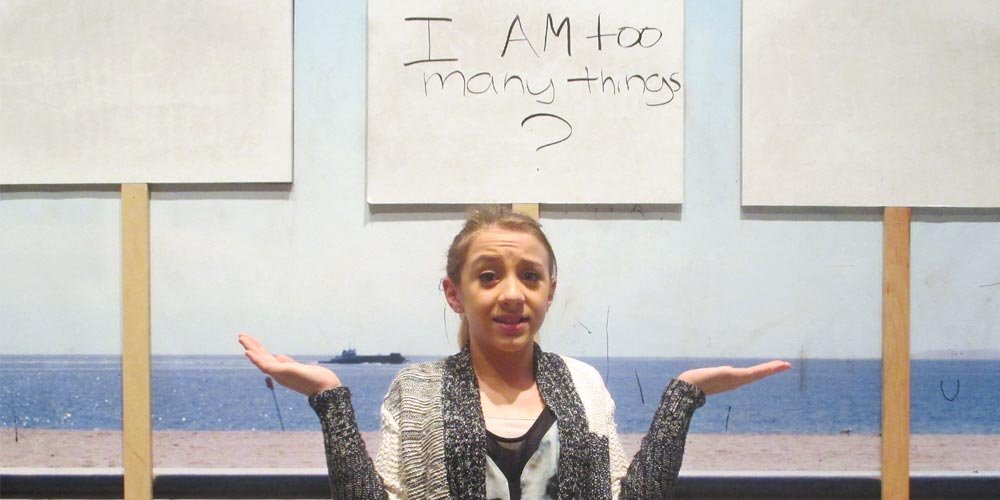

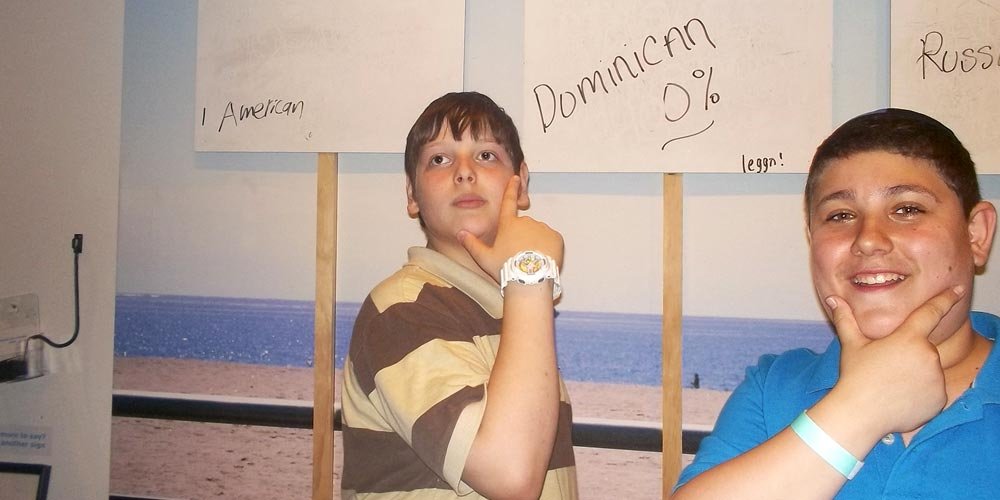

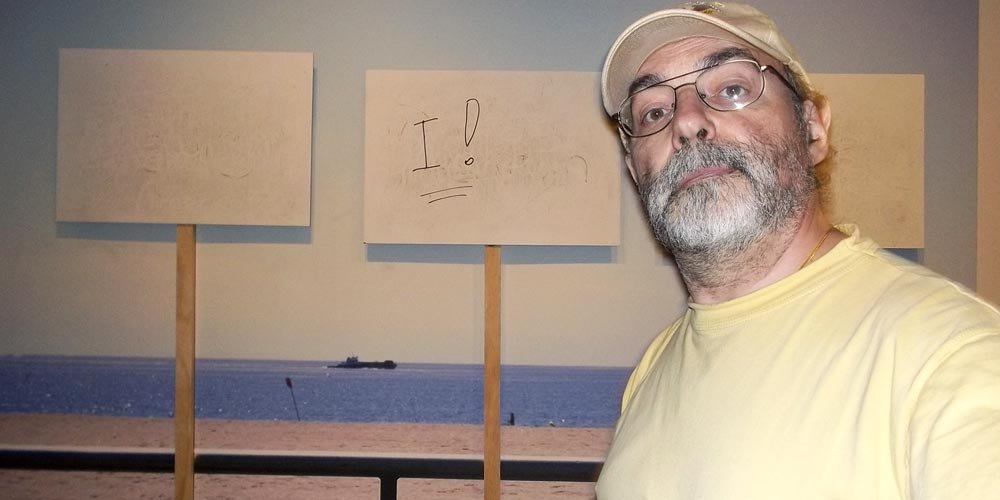

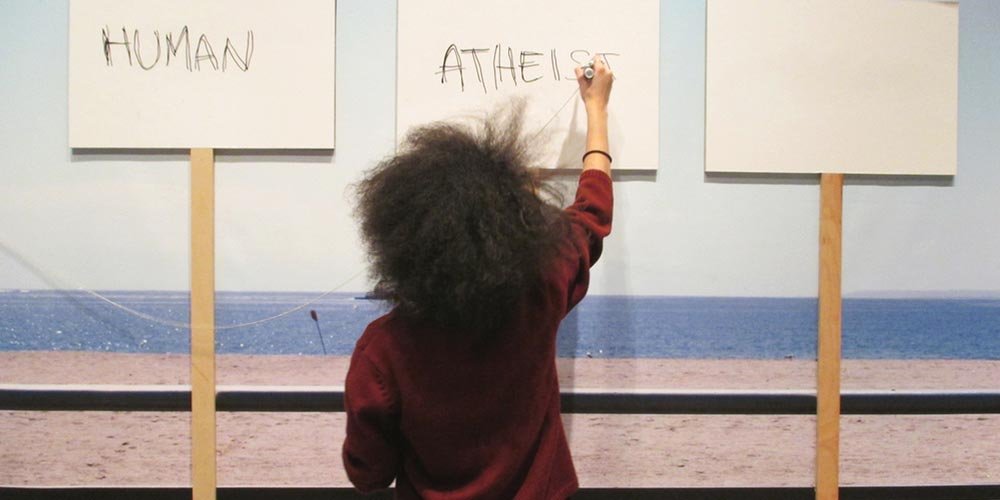

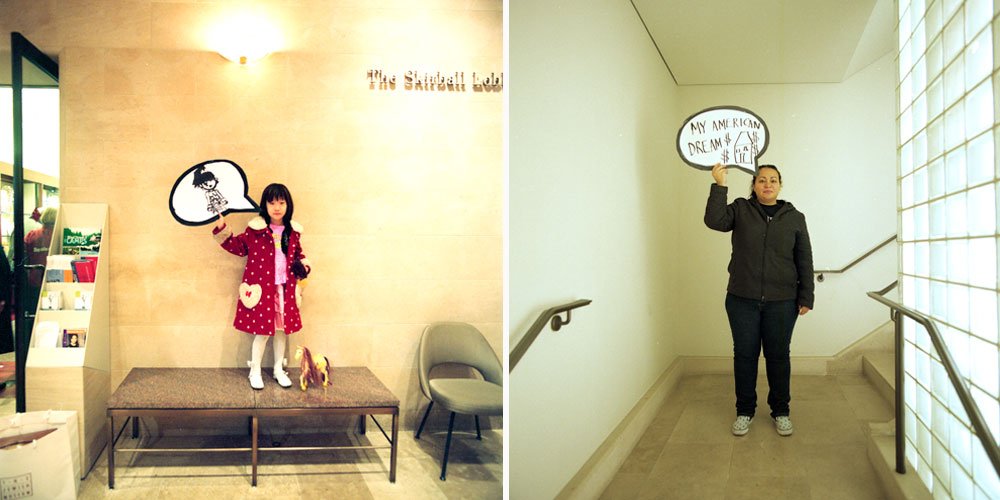

AMATEUR BIRDWATCHING AT PASSPORT CONTROL and MOST OF US ARE at TO SCATTER OR SOW: DIASPORA IN CONTEMPORARY ART

To Scatter or Sow: Diaspora in Contemporary Art serves as a central event for Wheaton’s campus-wide initiative to consider Diasporas: Economies, Boundaries, and Kinship. The title of the show is taken from the Greek root of the word, and evokes not only the dispersal inherent in diaspora but also the potential for rich growth. Framing the multi-faceted idea of diasporas through the work of eight contemporary artists, the exhibition includes video, photography, painting, ceramics and text-based work. The exhibition is presented both virtually and on the Wheaton campus. Artists: Alina Bliumis, Chinatown Pretty: Andria Lo & Valerie Luu, Isabella Cruz-Chong, Patricia Encarnación, Michael Gac Levin, Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow, Crys Yin.

Alina Bliumis, NARRATING AGAINST THE GRAIN Curated by Corina L. Apostol, Tallinn Art Hall, Estonia, July 17 - September 6, 2020

Where would you go if you wanted to see the centre of Europe? What are the traits of the average global citizen? What happens to our families when our political views are crossed? How can differences among us be re-defined in ways that enable resistance and creative activity for cultural change?

The “Narrating Against the Grain” exhibition features new commissions by Alina Bliumis and Tanja Muravskaja and will be open from 17 July until 6 September at Art Hall Gallery. The exhibition opening will take place on 16 July at 5 pm.

“Nations themselves are narrations,” observed Edward Said in Culture and Imperialism (1993), a statement that holds true in our current time. While conflicts continue to be waged over the ownership of land (and resources), issues of who has the right to work, live, settle and travel, and indeed the question of a nation’s future, are nevertheless echoed, challenged or even decided upon in narratives, both written and visual.

This exhibition brings together two artists who share the experience of growing up in Soviet Eastern Europe as well as a thematic interest in transcending borderlines, the constructed-ness of national identity, the entanglement of art and politics and the im/mobility of migrants. The global refugee reception crisis as well as the dramatic transformations in Europe during the pandemic have been catalysts for these artists to create artistic narratives that go against the grain and engage with forms of being in-between geographies and the struggle over self.

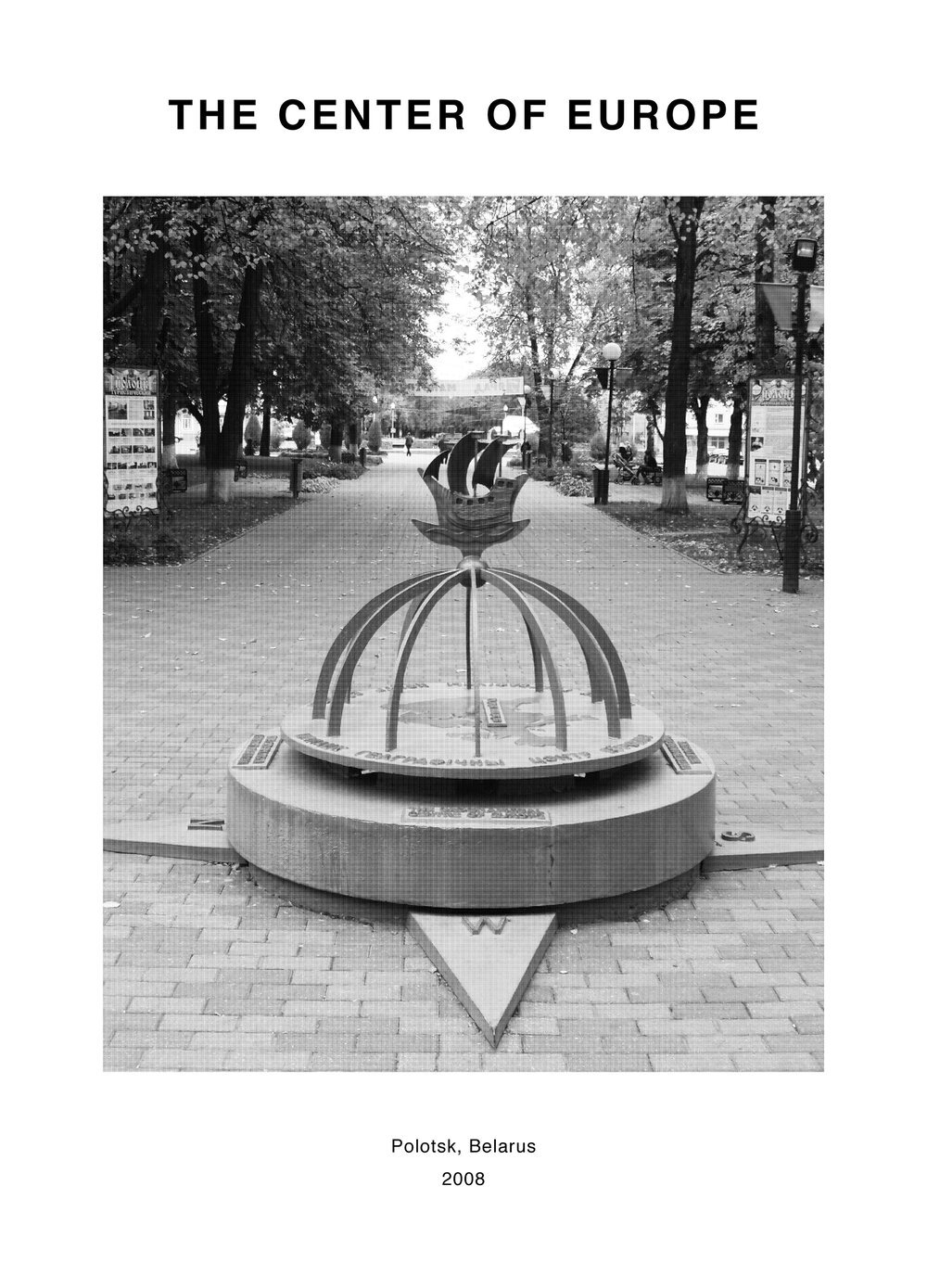

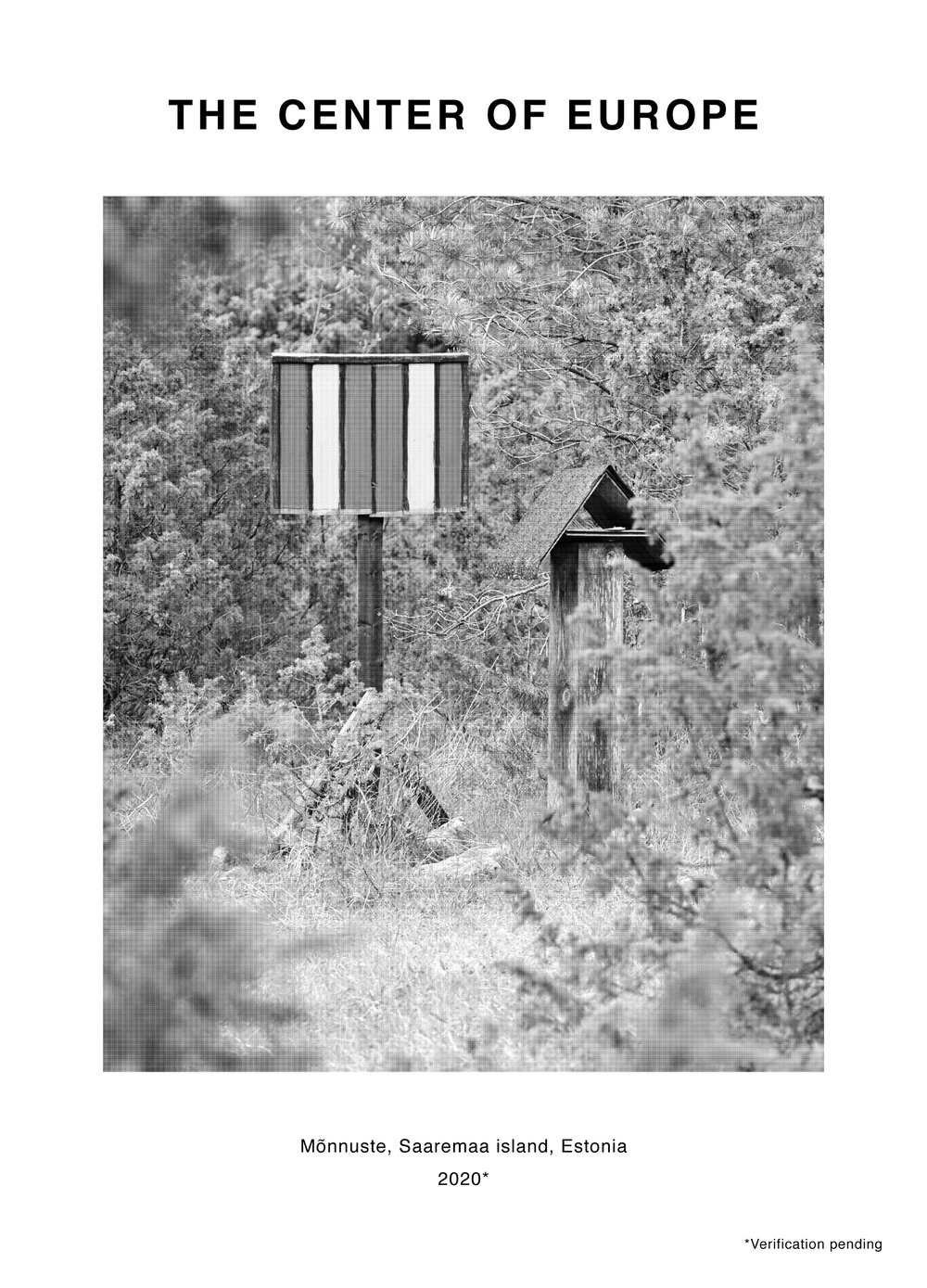

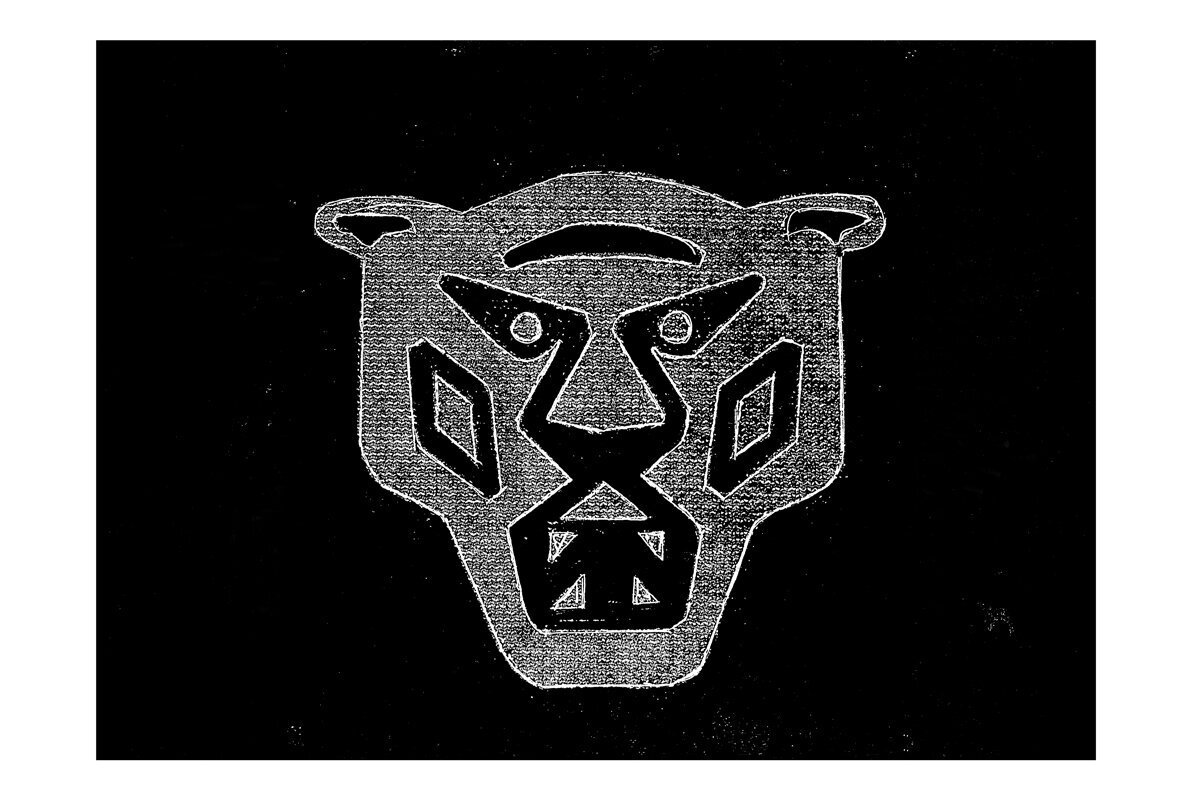

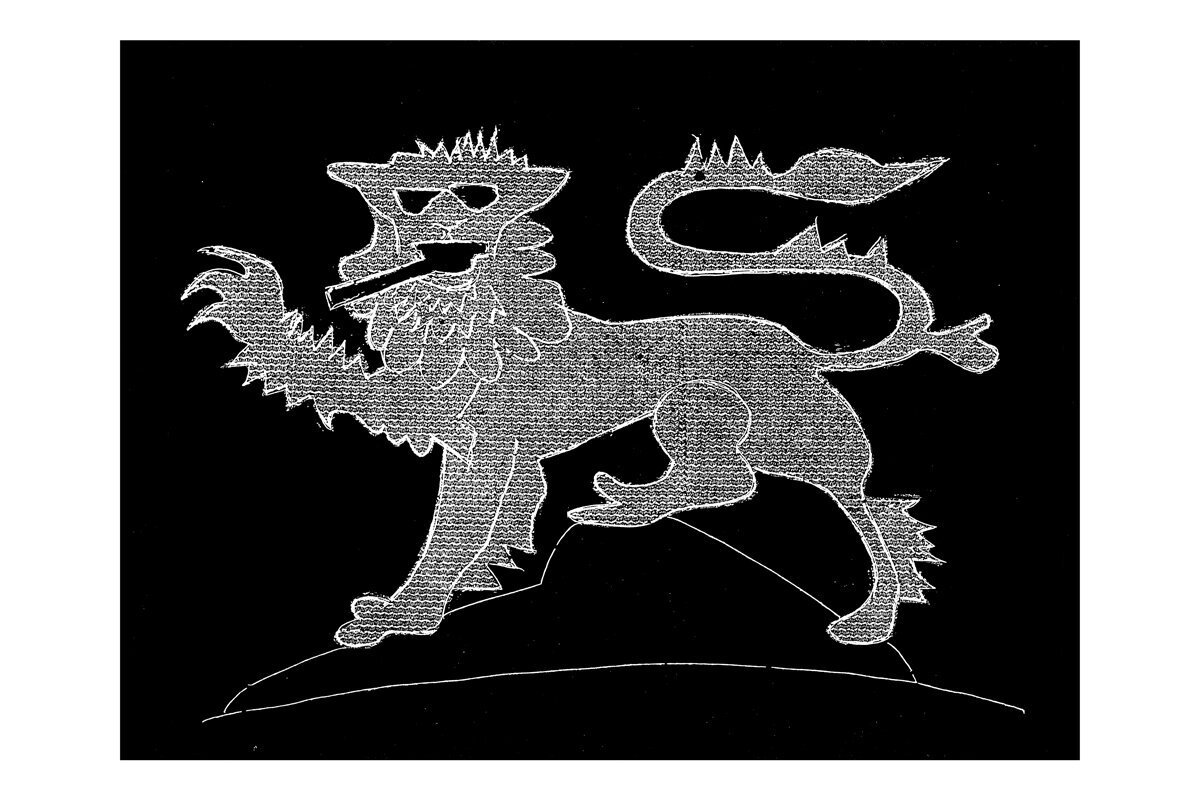

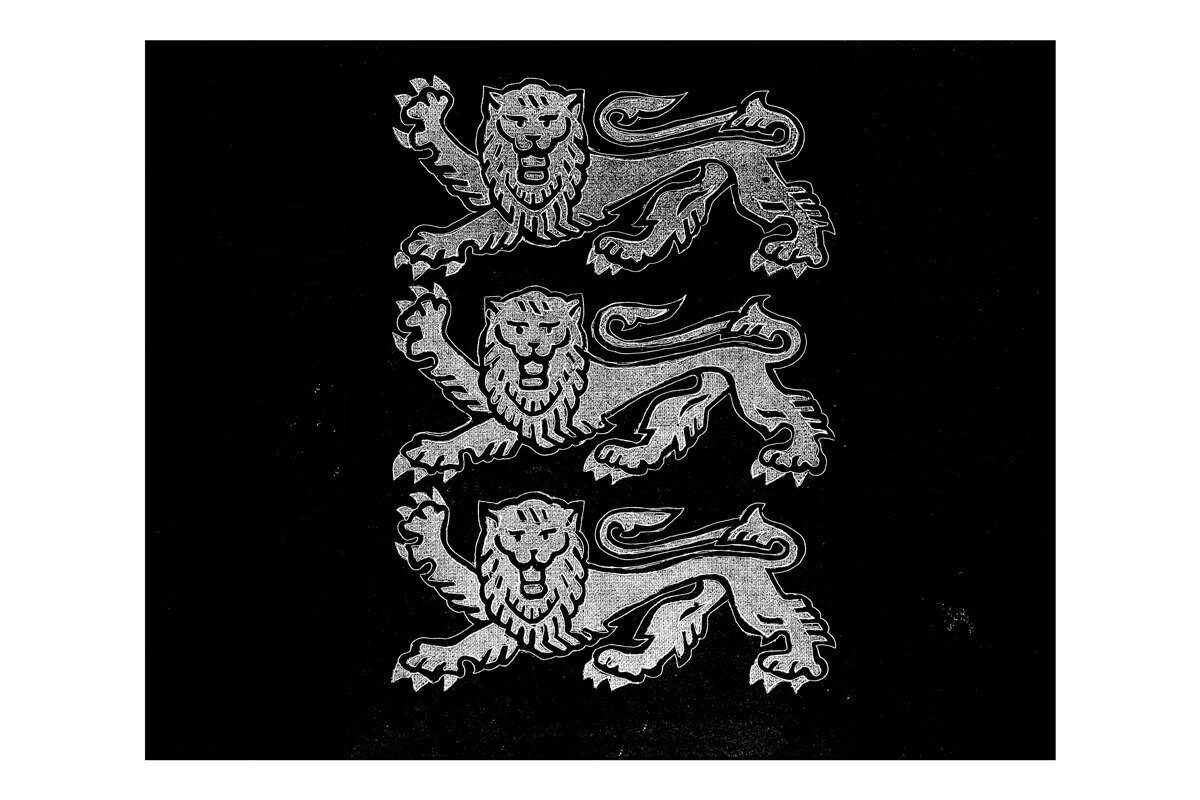

With humour and empathy, this project, the first collaboration between artists Alina Bliumis and Tanja Muravskaja, will introduce inventive forms of togetherness at the intersection of art, politics and education. The project specifically consists of a physical presentation of photographs and interviews of life under the pandemic with at-risk, vulnerable, resilient members of society, a series of banners emblazoned with different types of big cats from national passport covers presented at the gallery and partner cultural institutions (including Nõmme Cultural Centre, Estonian Art Academy, Museum of Photography, Tallinn Russian Museum) posters of different centres of Europe highlighting the shifting definitions of borders, and more.

While the physical exhibition will take place at the Art Hall Gallery and across Tallinn, the curator and artists will also engage audiences in lively online discussions on the consequences of the emergency state and reflect on the challenges and opportunities of mutual aid and solidarity, as well as new modes of engaged citizenship.

The exhibition will grapple with the possibilities that art and culture offer and respond to current reimaginings over citizenship and homelands. Building upon the experiences of two artists who share a personal history of migration across cultures and borders that have greatly influenced their work, the exhibition will help facilitate exchanges that will have a lasting effect upon public opinion. Ultimately, “Narrating against the grain” aims to reflect upon the contingencies of our time, urging all of us to take an active role as agents of change.

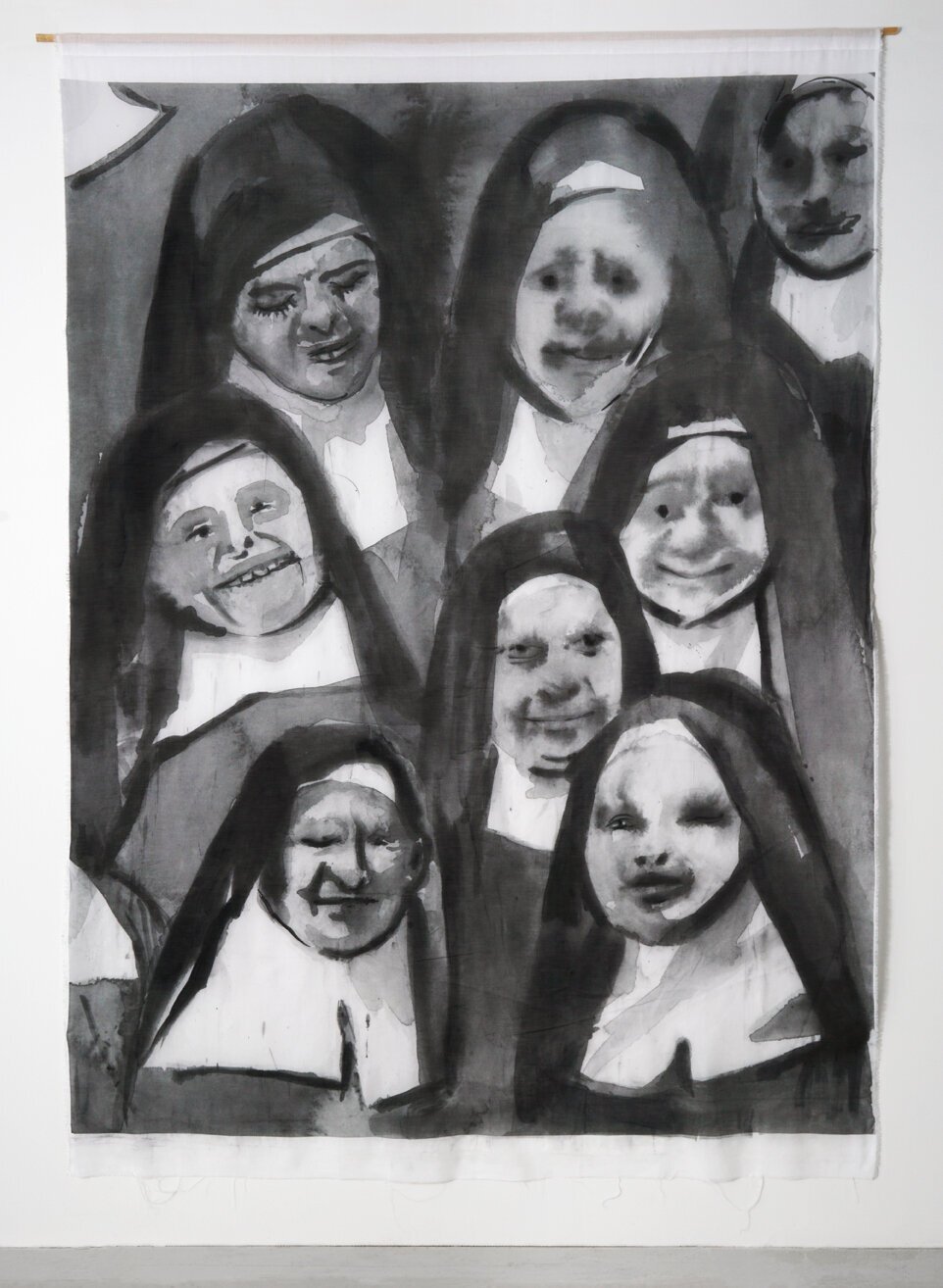

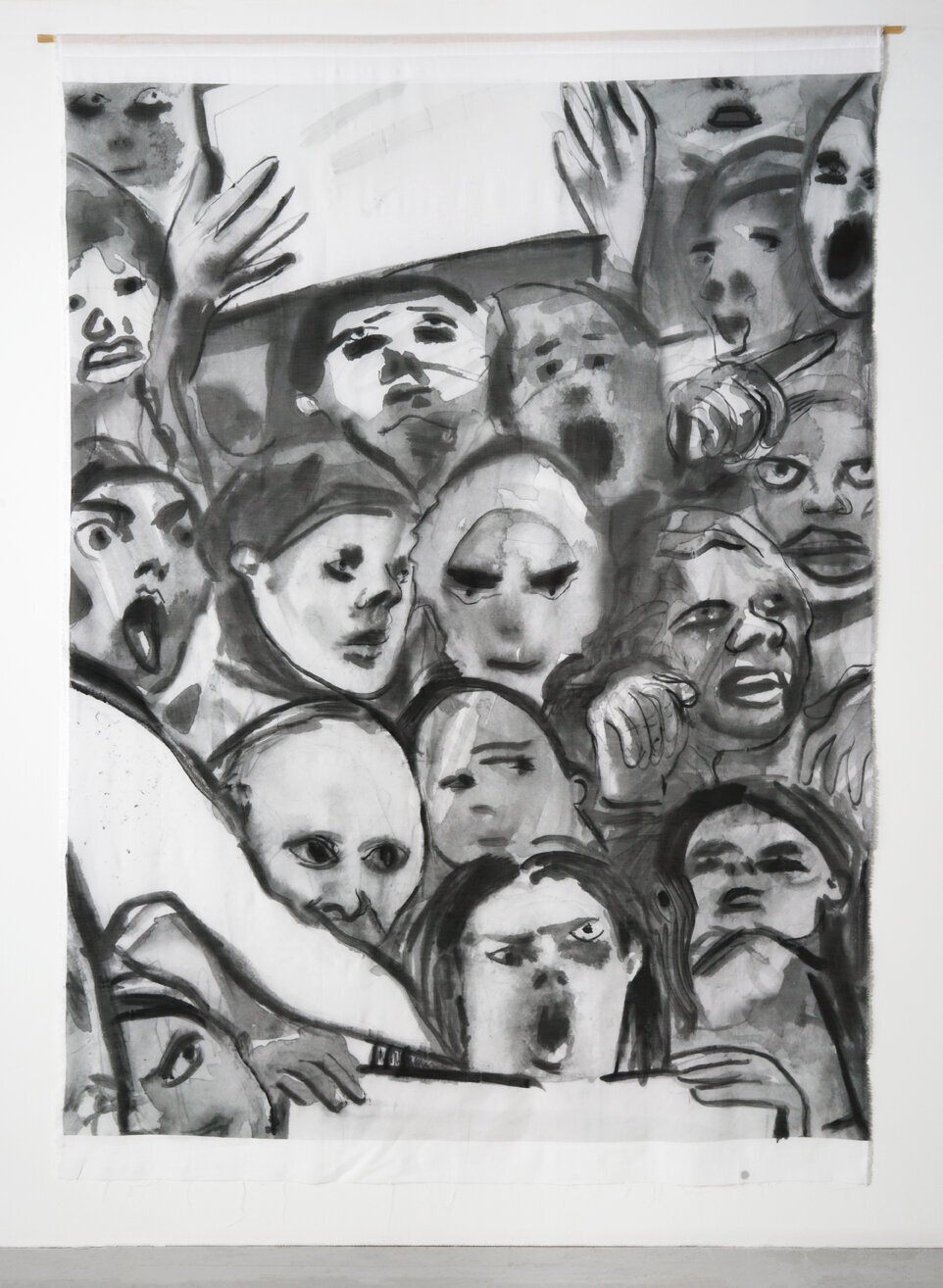

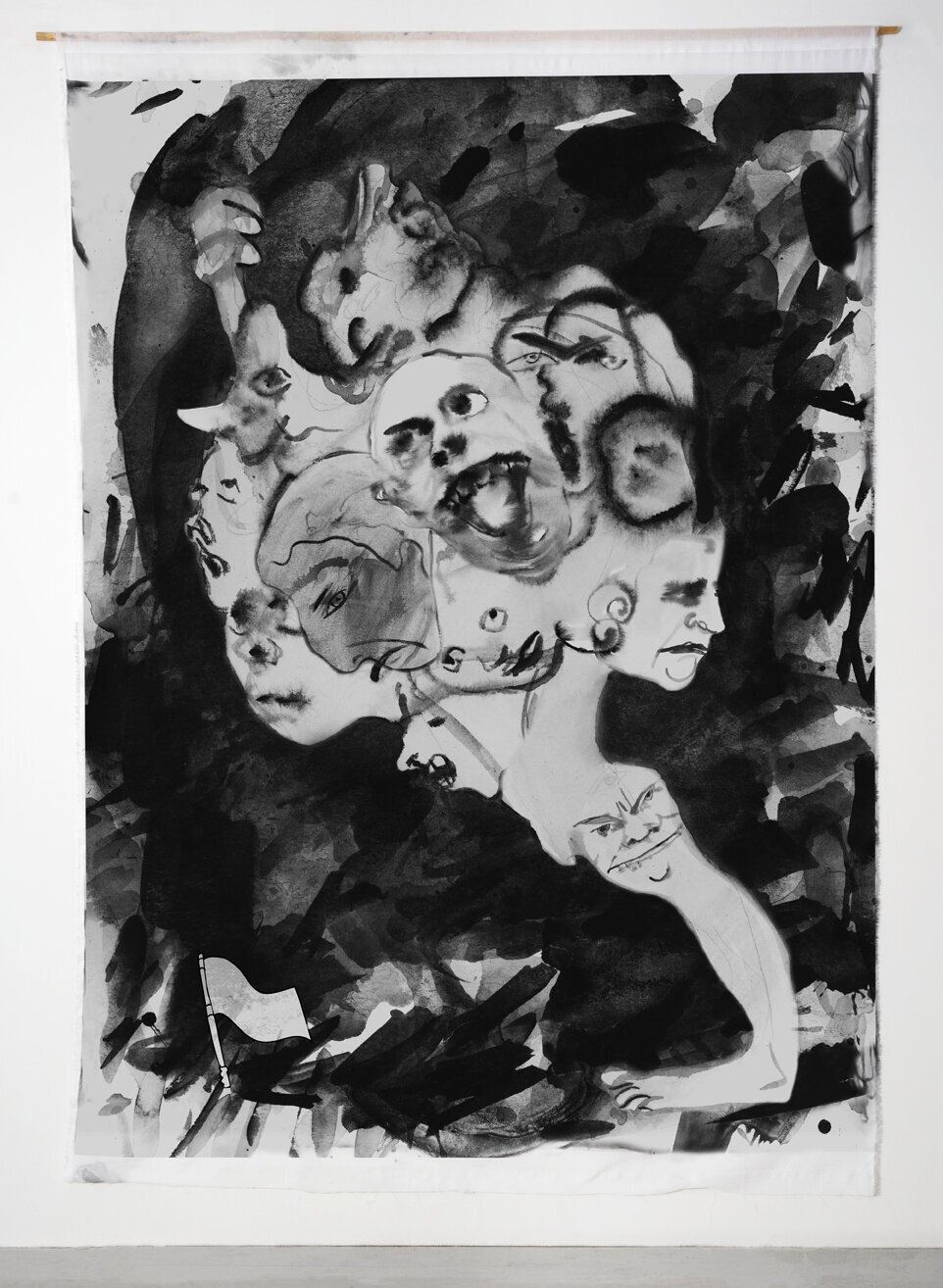

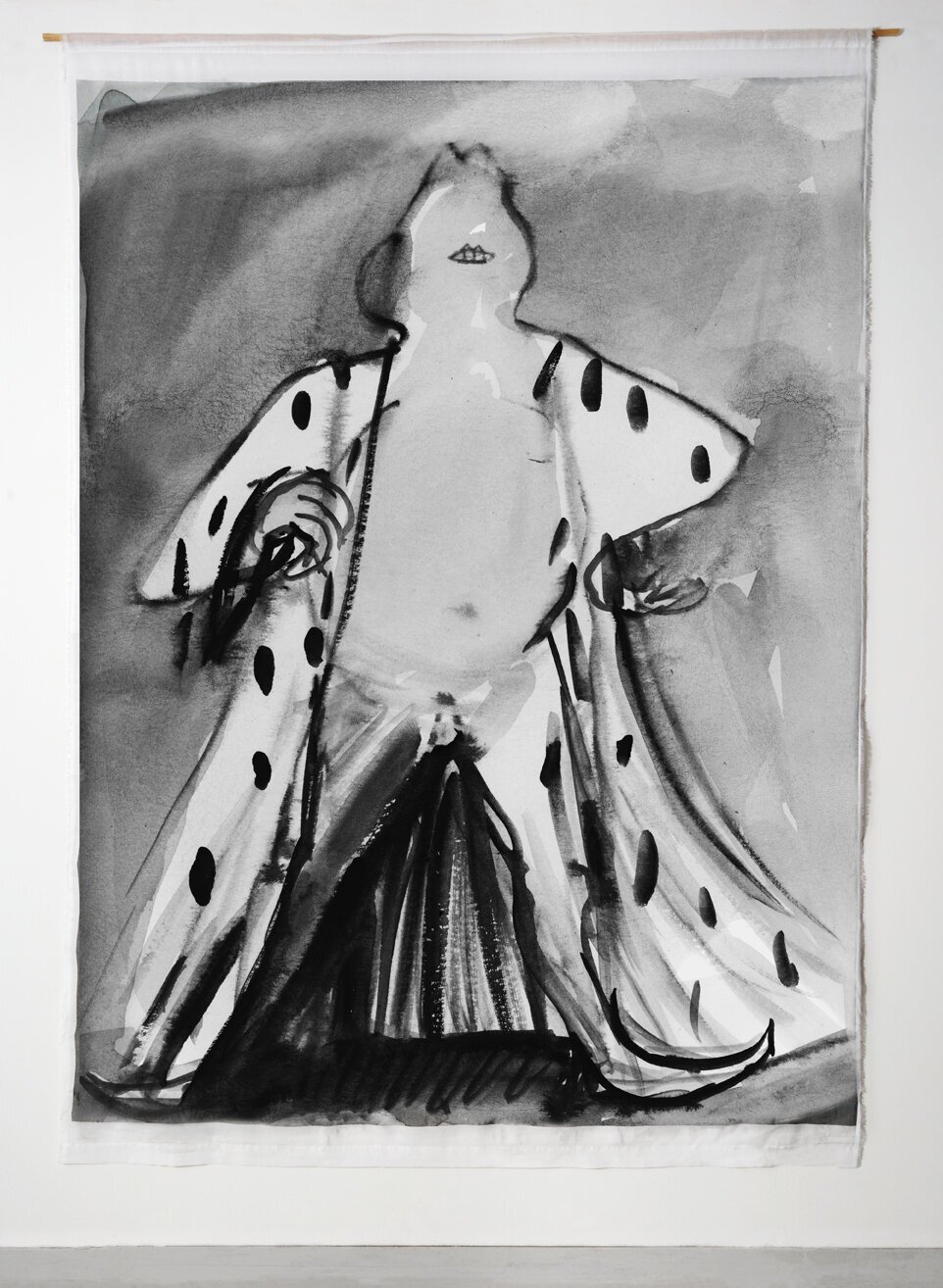

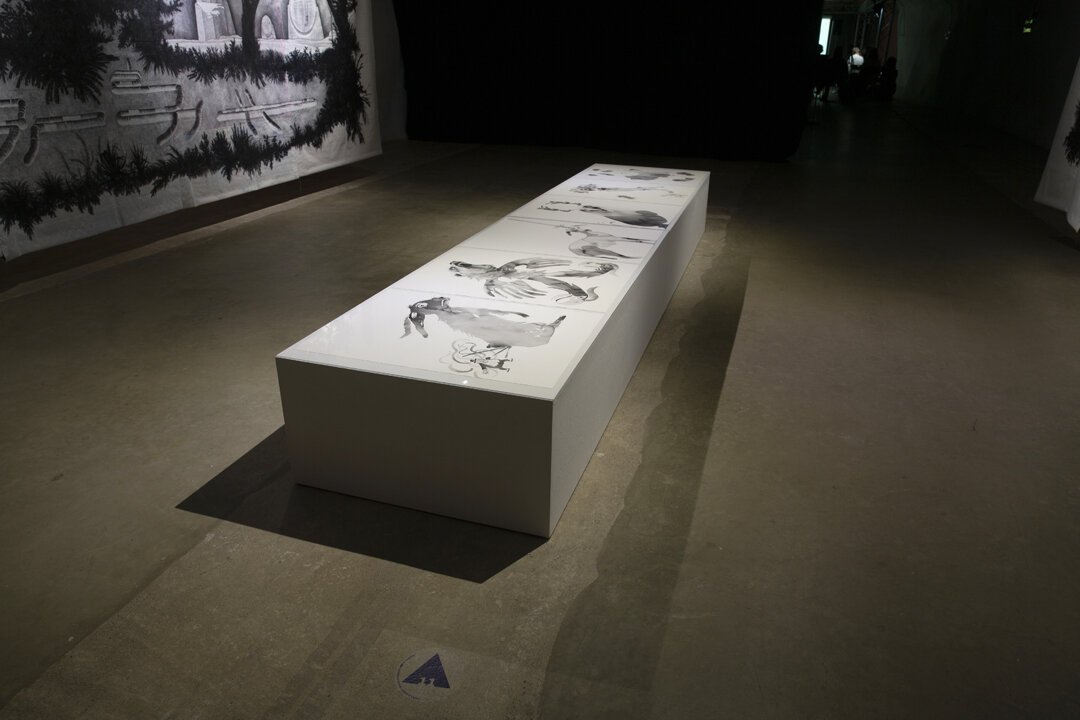

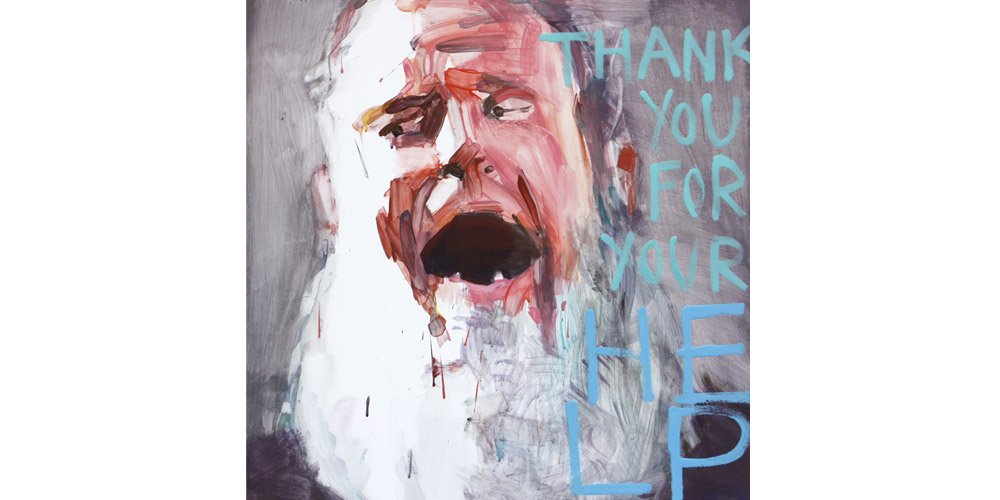

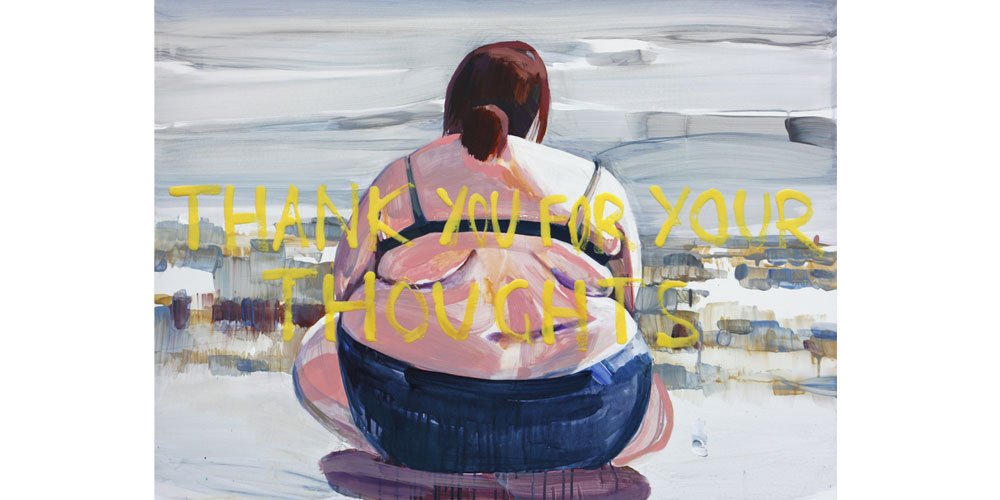

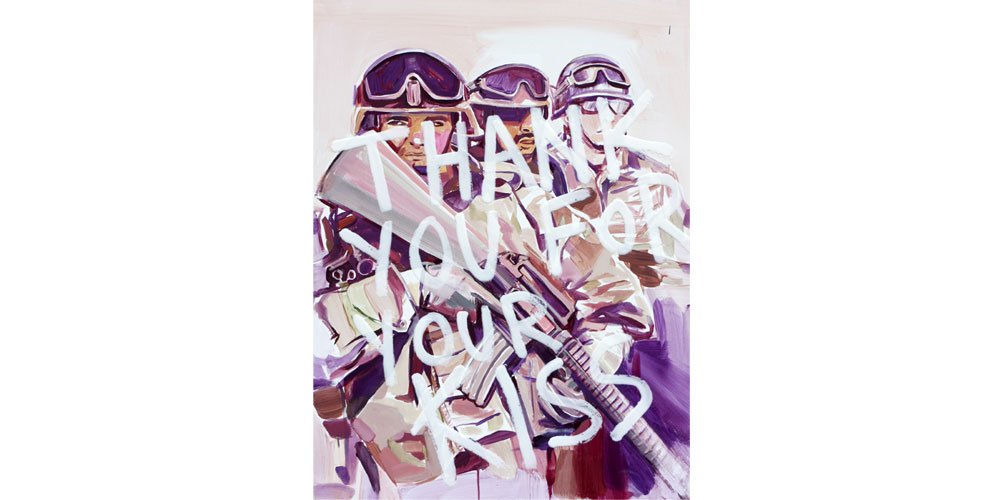

Alina Bliumis, MASSES Curated by Elizabeth M. Grady SPRING/BREAK Art Show March 3-9, 2020

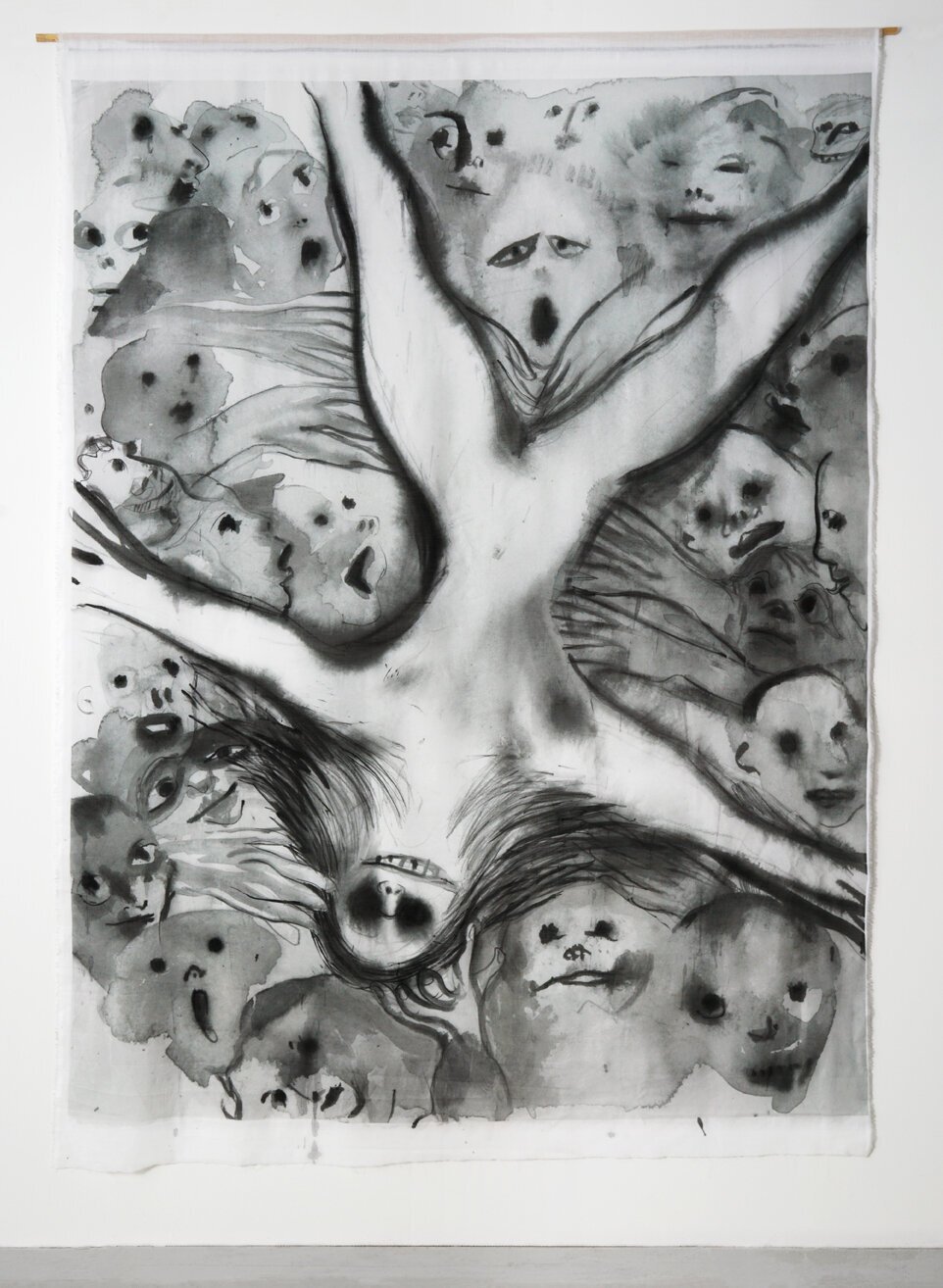

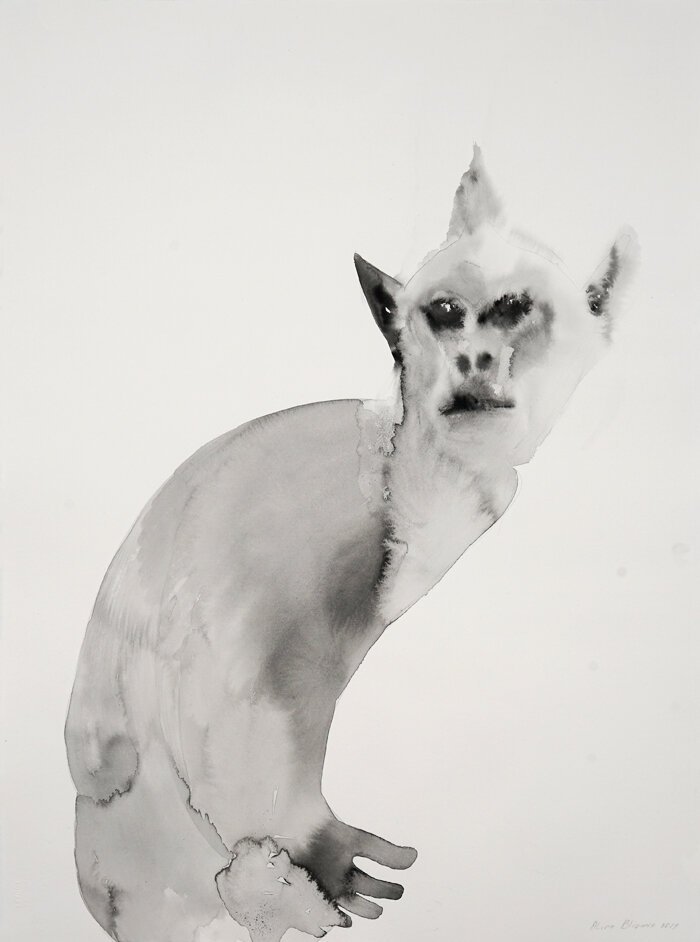

The series Masses (2019-2020), by Alina Bliumis is an exploration into the tipping point, where analysis becomes obsession and participation becomes dissolution, as the individual relinquishes a sense of self in the face of phenomenological overwhelm. At 58 x 83” the cotton panels that comprise the series depict crowds of over-life-size figures representing internal and external encroachment on the psyche. To pass between and among the mono-chrome gossamer hangings, which combine digital print and watercolor, is to revisit each time you’ve experienced that transcendent moment of fear or ecstasy where the only certainty is that you’ve given up your personal agency to the mob.

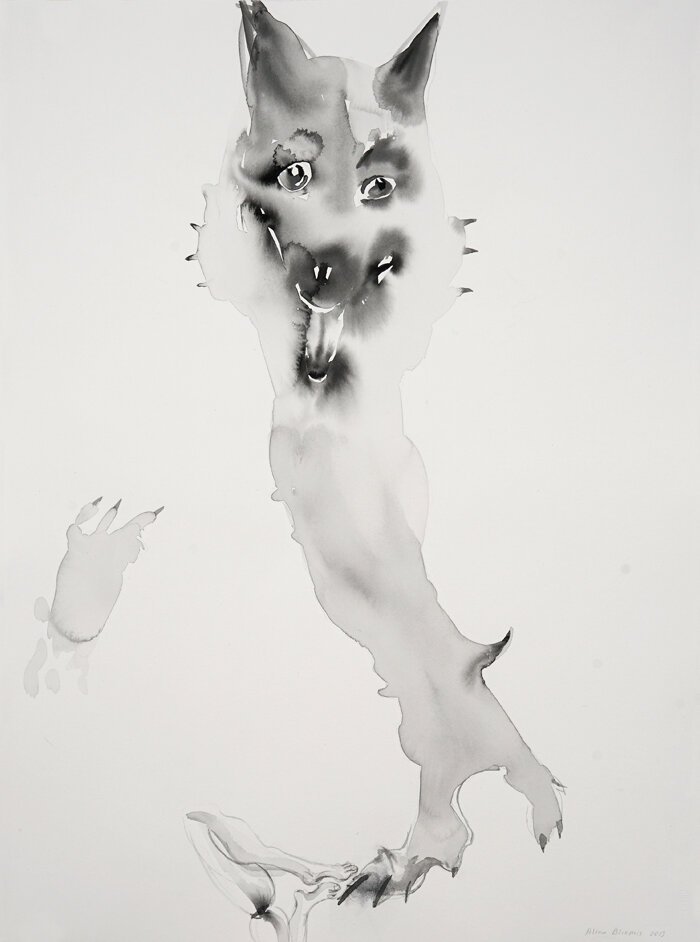

Masses #1 is perhaps the most anomalous of the series, focusing as it does on an internal struggle. Evoking the howling forces of worry and self-doubt that visit in the blackness of the small hours of the morning, the work suggests a descent into a demon-plagued hell of our own device. Monstrously twisted and disembodied limbs vie with attenuated spectral faces for command of the poor soul, bent over at the base of the composition, and gazing apprehensively over its shoulder at the reigning chaos. As riveting as it is disturbing, it is Fuseli’s Nightmare for our troubled times.

On a lighter note, Bliumis turns to mass celebrations of Dionysian excess in the rock concert depicted in Masses #2. The main figure is blissed-out and spread-eagled in mid-stage-dive. The darker side of the experience is intimated by the blackened eye sockets and inverted pose of the figure, however, and we are left to question whether the stage divers act is a celebration of music and communal experience or a kind of temporary martyrdom, where consciousness is sacrificed through the use of drugs for release from the pressures of this mortal coil. The veiled reference to St. Peter, who as legend has it asked to be crucified head-down so as not to risk dilution of the memory of Christ’s torture, cannot be lost on anyone familiar with the Western tradition.

Front-page news often records crowd hysteria, and the palette of Bliumis’ series reinforces the newspaper reference in works like #7-8 and #5 which depict a Protest and Soldiers respectively. In the former, there are as many emotions as faces, showing the rage, fervor, anxiety, devotion, and hope that can forge a compelling collective identity at mass demonstrations. Yet one is left to wonder, given the multiplicity of expressions, if these protestors will ever achieve unity of communal purpose. The soldiers, in their uniformity, are a stark reminder that in rigid discipline and conformity comes another kind of excess that can be wielded as a blunt and unforgiving weapon against a mass of individuals.

Abandonment of reason is a theme that carries through several of these panels, not least in the Masses #3 (Lovers). Here, bodies entwine in the abandonment of an orgy, with the ebb and flow of momentary sensations evoked by shifts in scale, as in the couple at center right; or the union of body parts, like the heads at the bottom center, whose mouths unite when the tongue of the head on the right becomes the lips of the head on the left, in a perceptual twist that would have made Cezanne proud.

The installation of the works, as large fabric panels dividing the space, will create a disorienting experience for viewers, ideally, a psychological state that hints at if not approximates the loss of self-experienced when one becomes part of a crowd or mass, whether for good or for ill, ecstasy or violence. Bliumis depicts scenes where mass experience tips over into mass hysteria, where the intellect is overcome by emotional input. What differentiates a rally from a revolution? A riot from a rock concert? Whether attending a military exercise, a religious rite, or an orgy, overload provides release through collective identification with a larger purpose.

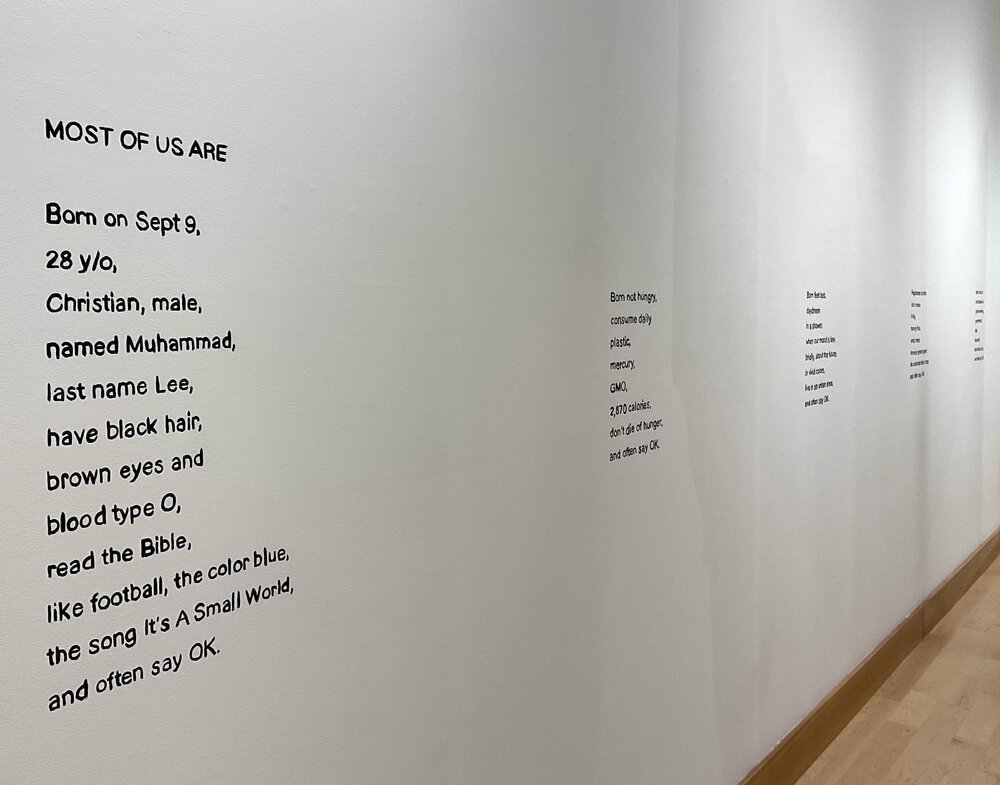

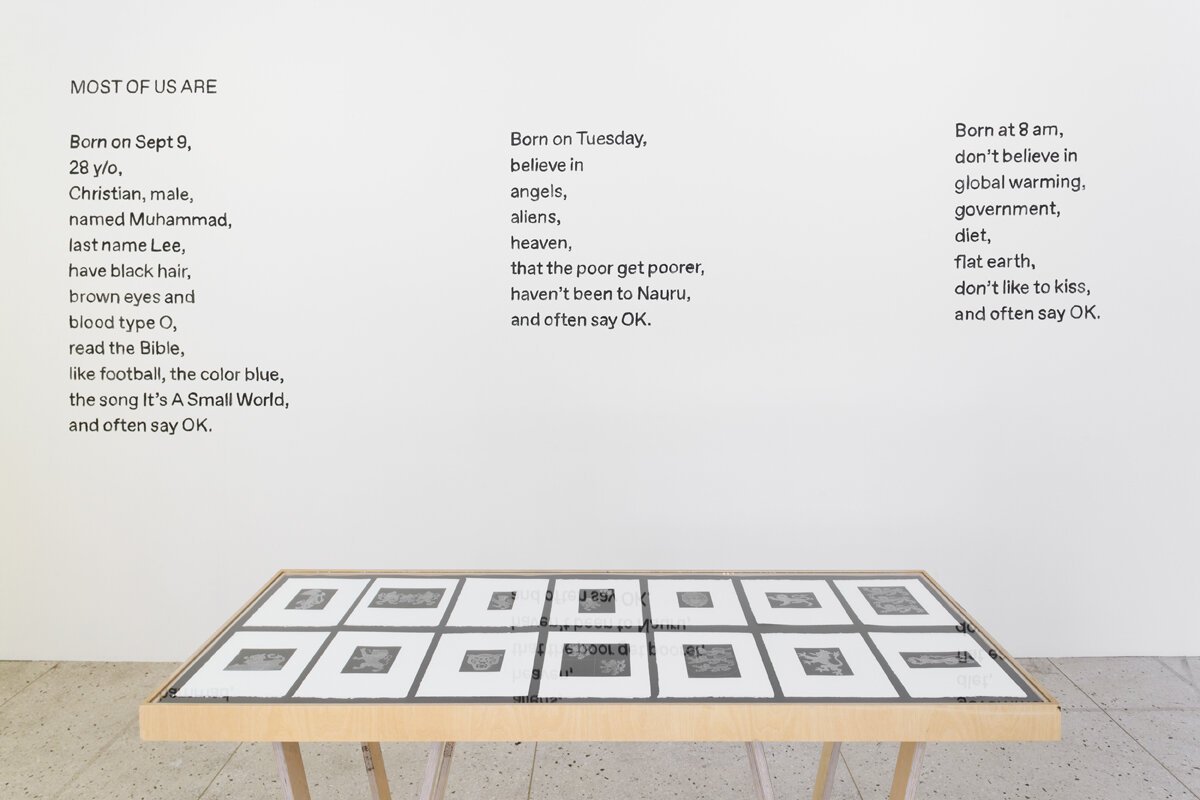

Alina Bliumis, CLASSIFICATION PATTERNS: CHRISTIAN, MUHAMMAD, LEE Curated by Irena Popiashvili “Ў” Gallery of Contemporary Art, Minsk, Belarus October 9 – October 31, 2019

The “Ў” gallery of contemporary art is pleased to present a solo-exhibition by the Belarus-born artist, Alina Bliumis. The artist was born in Minsk, but she received her education in New York and has exhibited extensively in the US and in Europe. This is Bliumis’ first solo exhibition in her native Belarus.

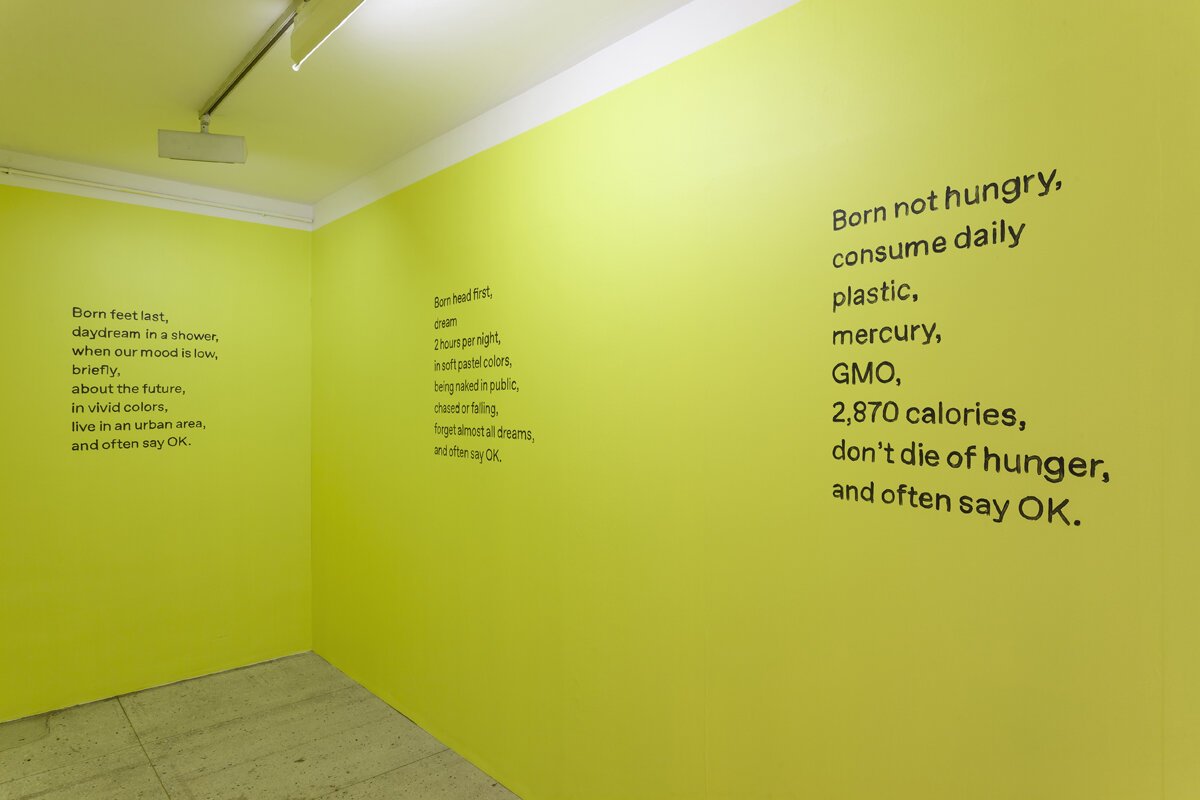

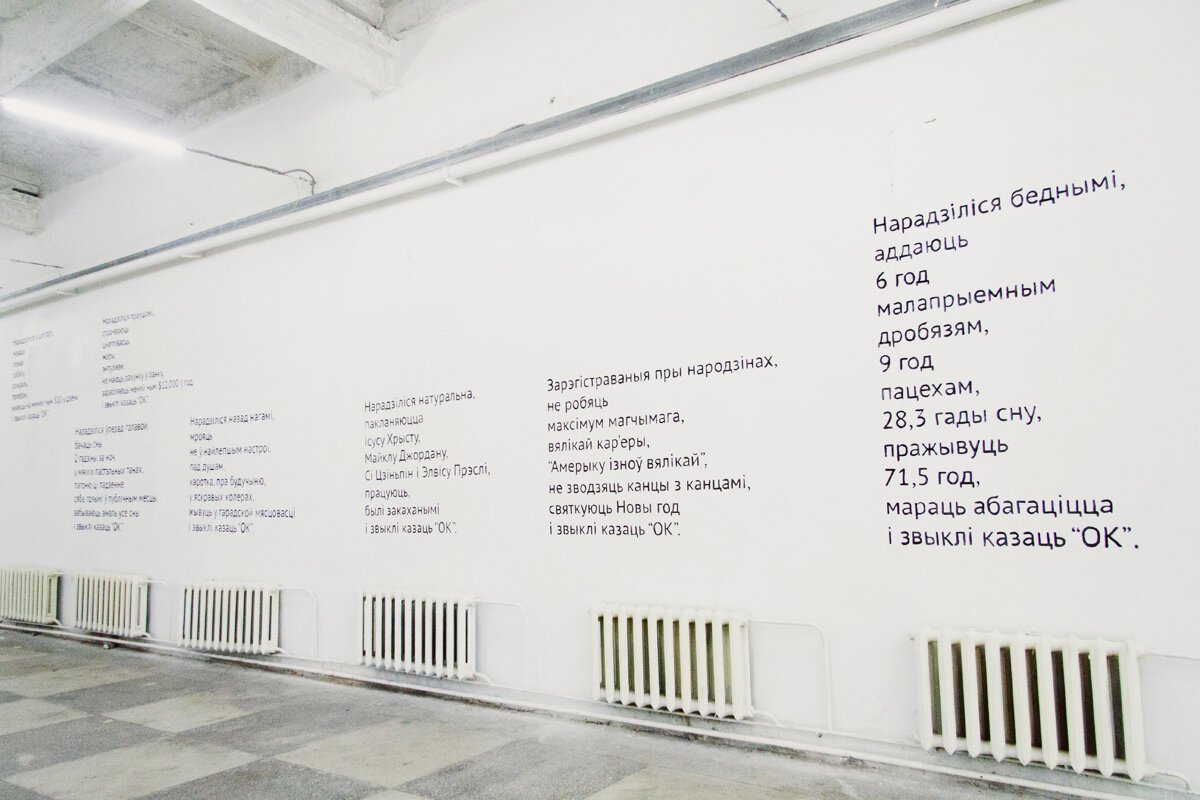

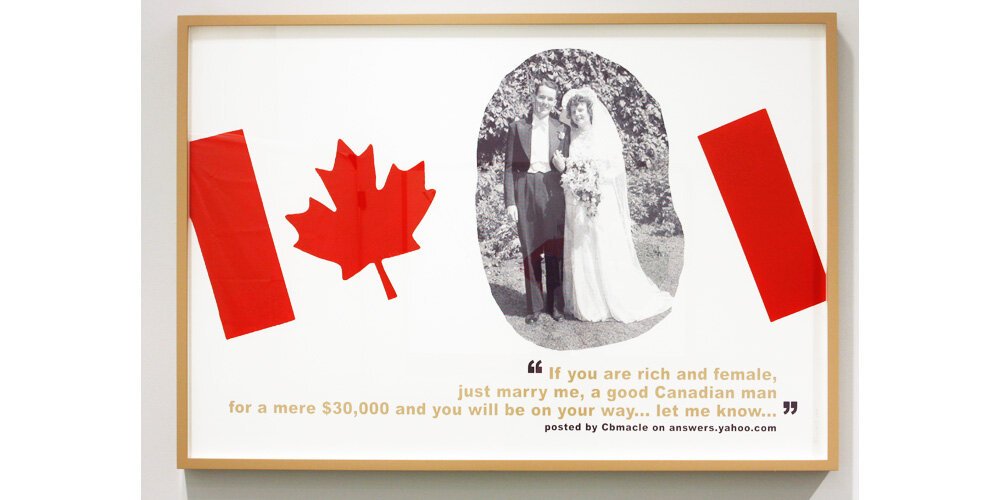

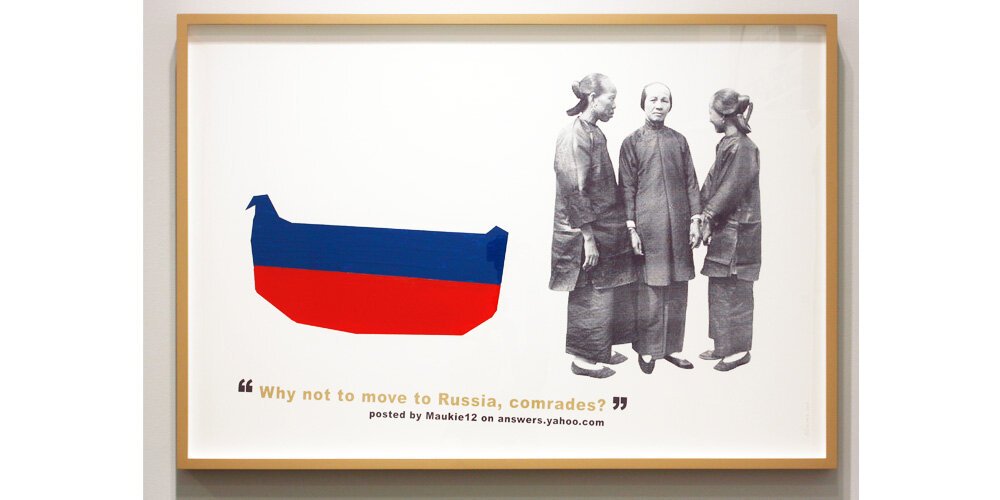

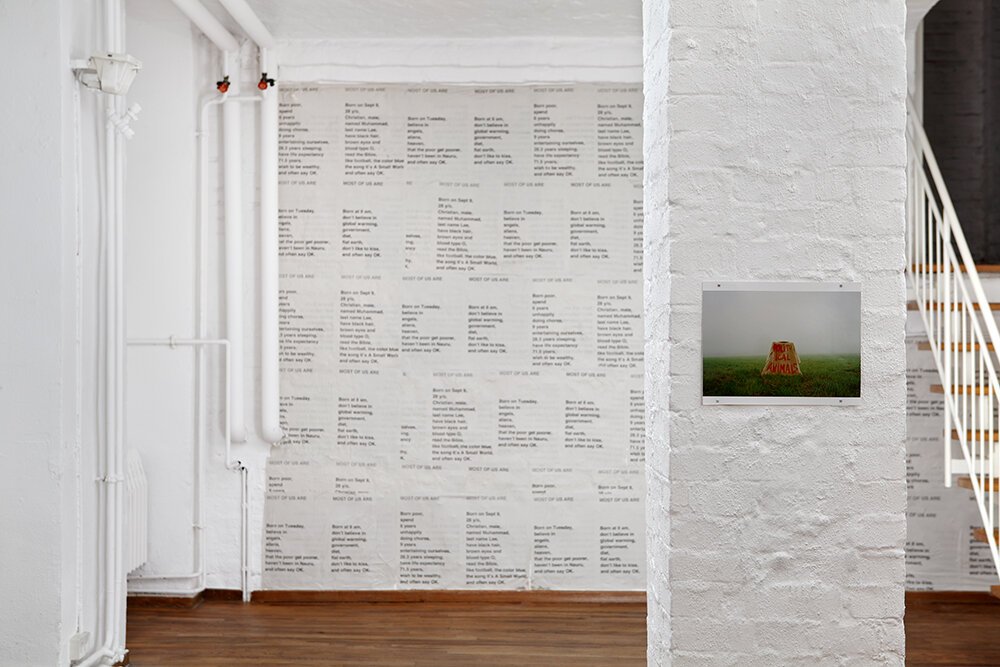

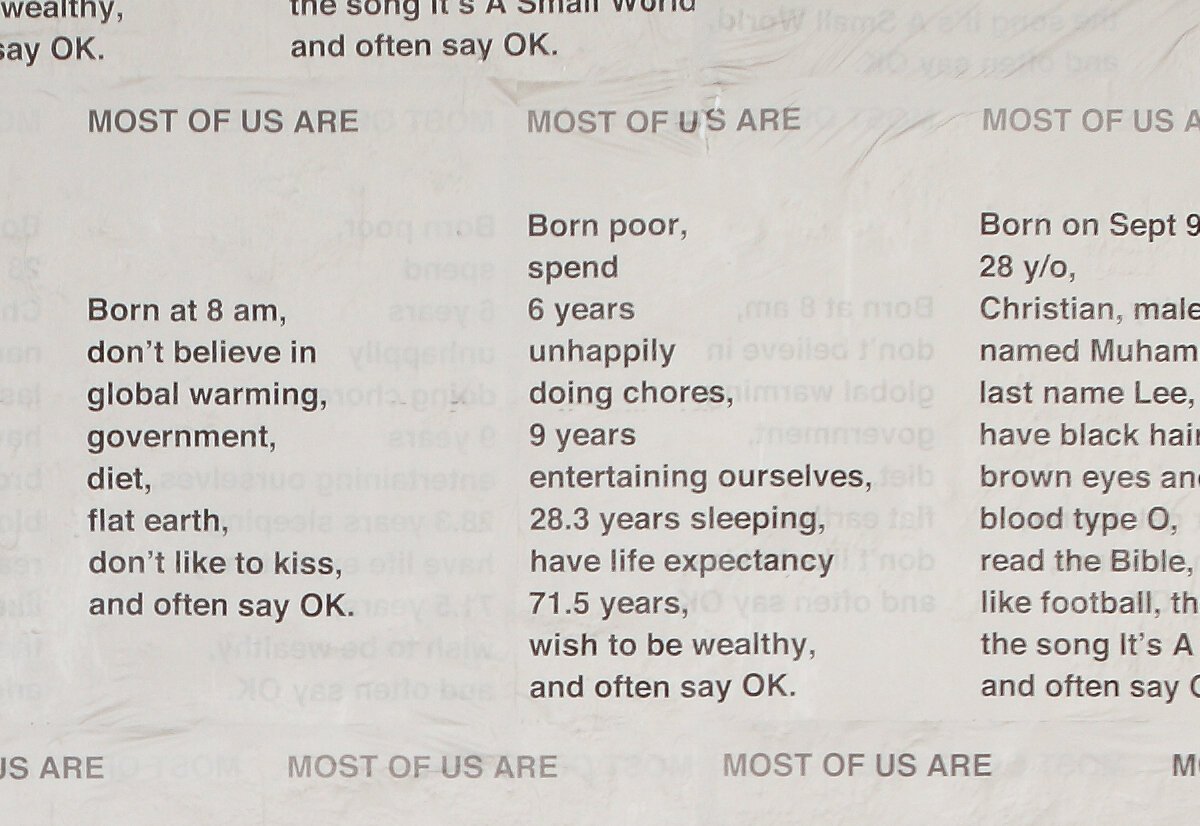

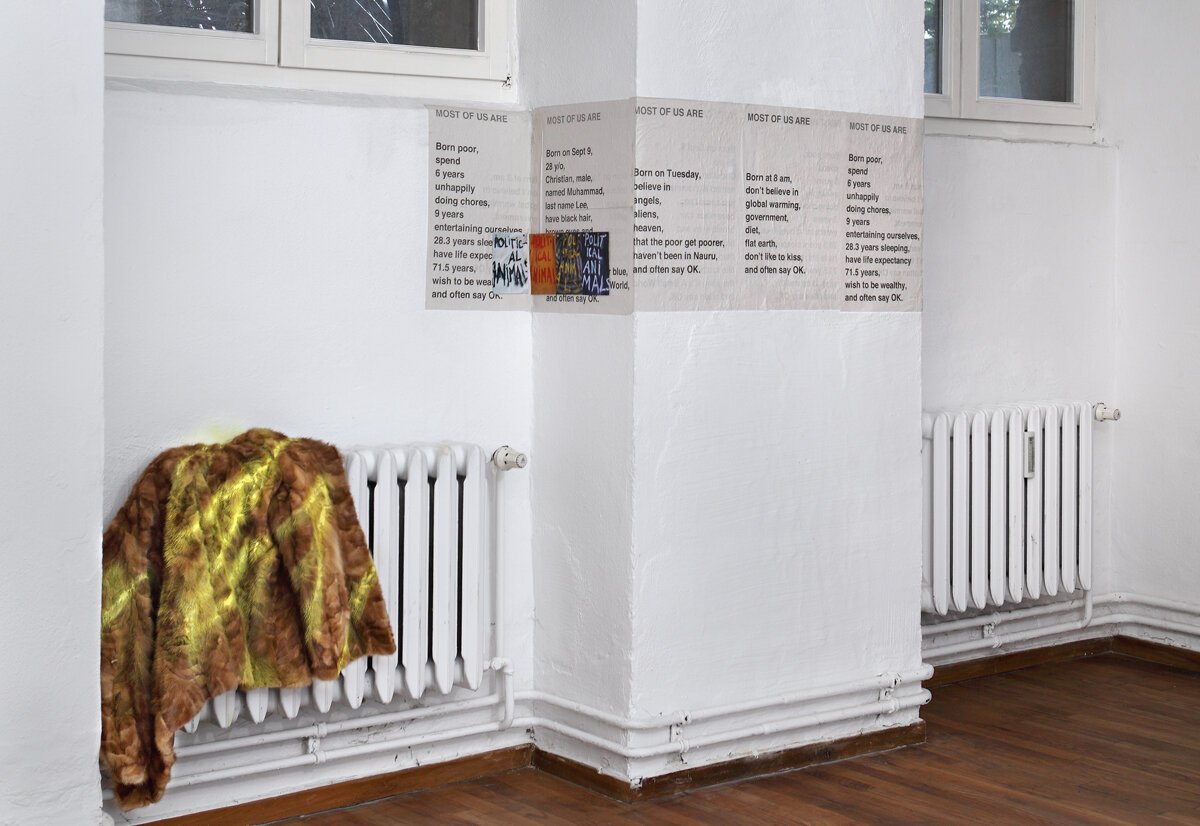

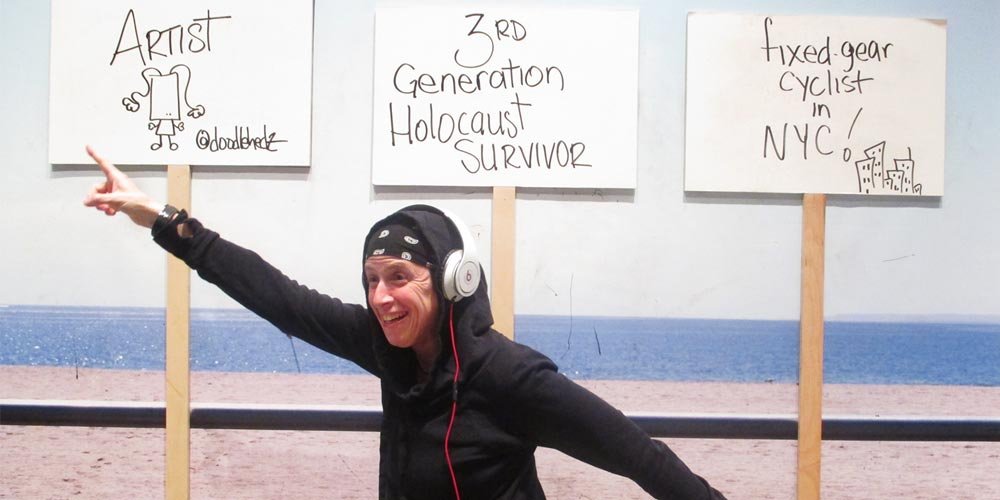

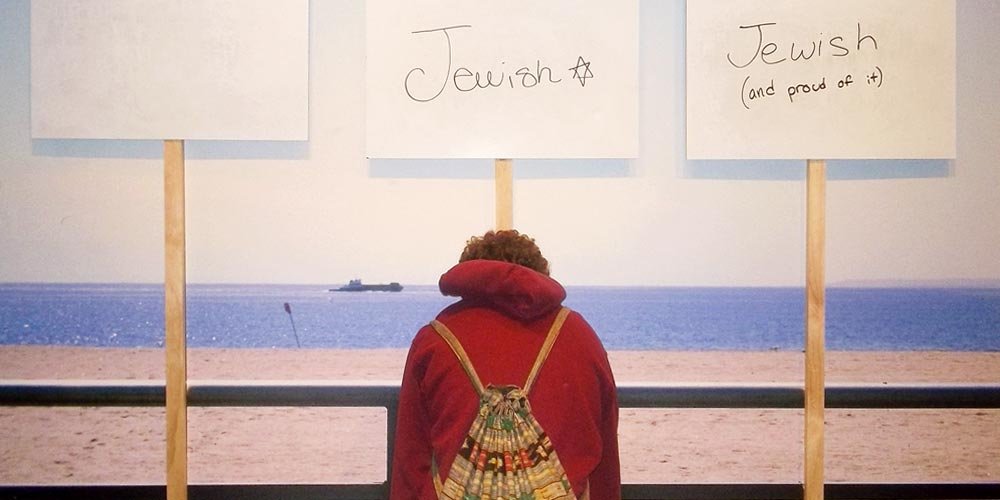

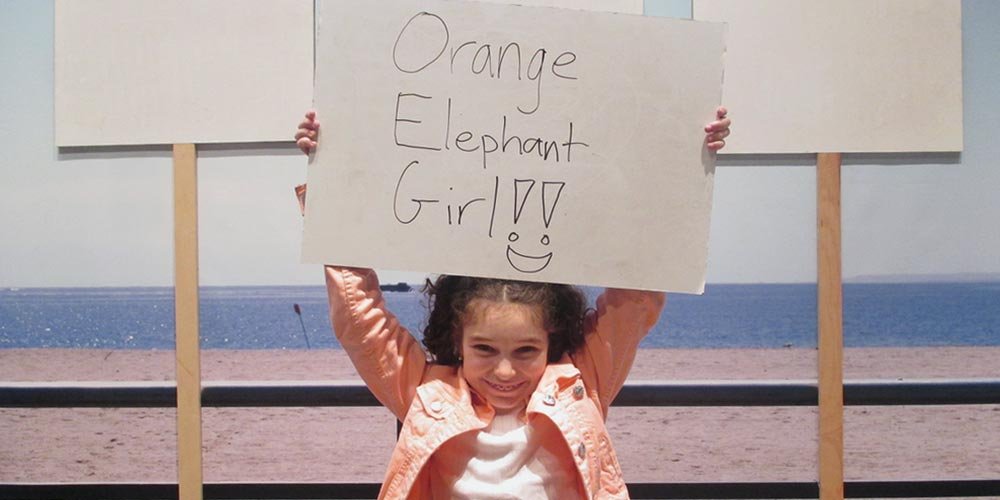

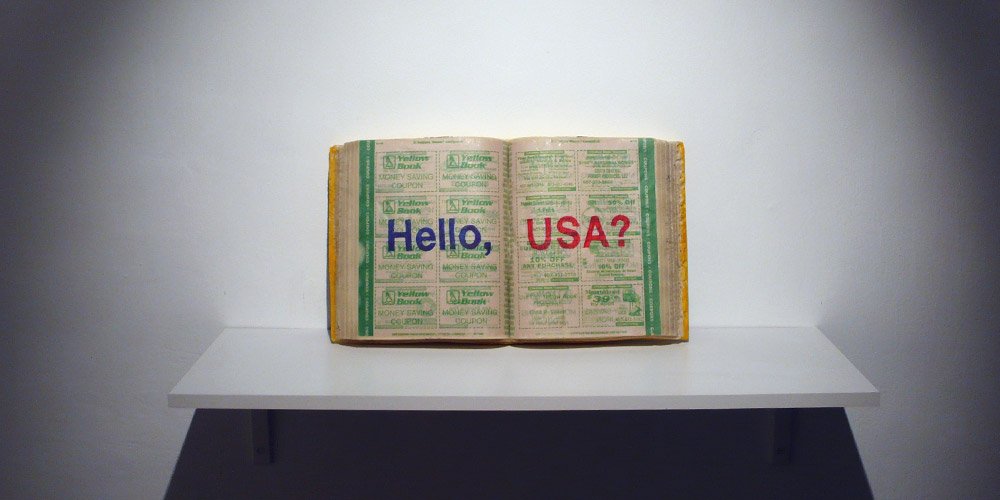

The title of the exhibition refers to the artist’s 2018-2019 text-based series Most of Us Are. This 12 part work describes how “most of us” are born, believe, worship, don’t eat, consume, own, lose, dream, and spend our lives. Bliumis used statistics, demographic research and opinion poll data to define the main characteristics of a global citizen, and then construct a verbal portrait of “the most typical person.” Statistically, it is correct that “most of us are named Muhammad, last name Lee.” But as Stamatina Gregory noted in her text on Bliumis’s work (Political Animals, Aperto Raum, Berlin, 2018), “no citizen of the world cobbled together from shared demographic data truly exists.” And Bliumis’ statistic-based text portraits are anything but typical. Classifying, researching, collecting and creating new patterns of order is essential to the artist.

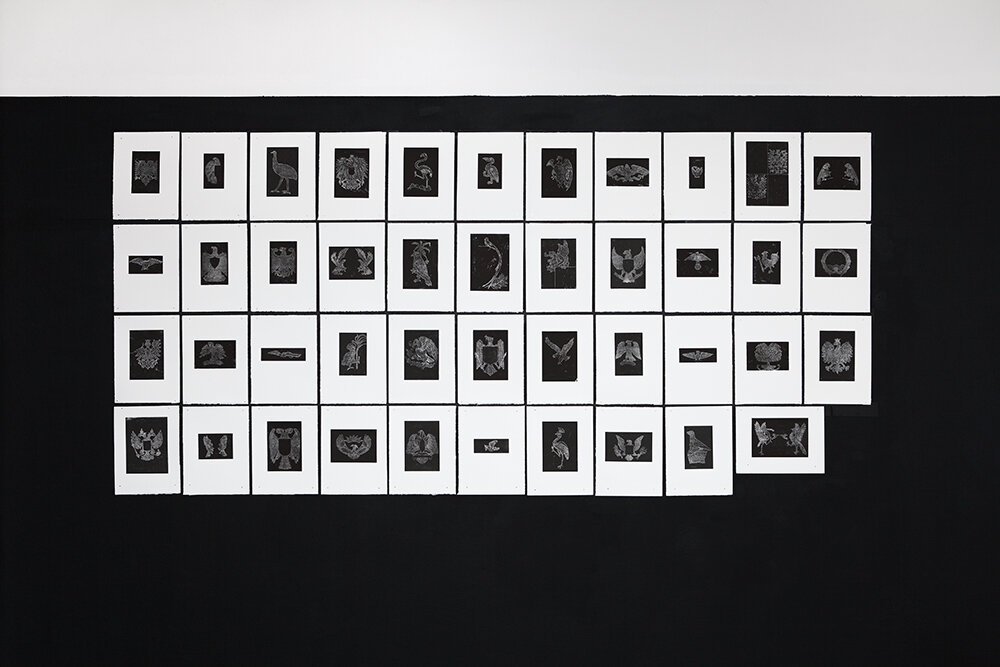

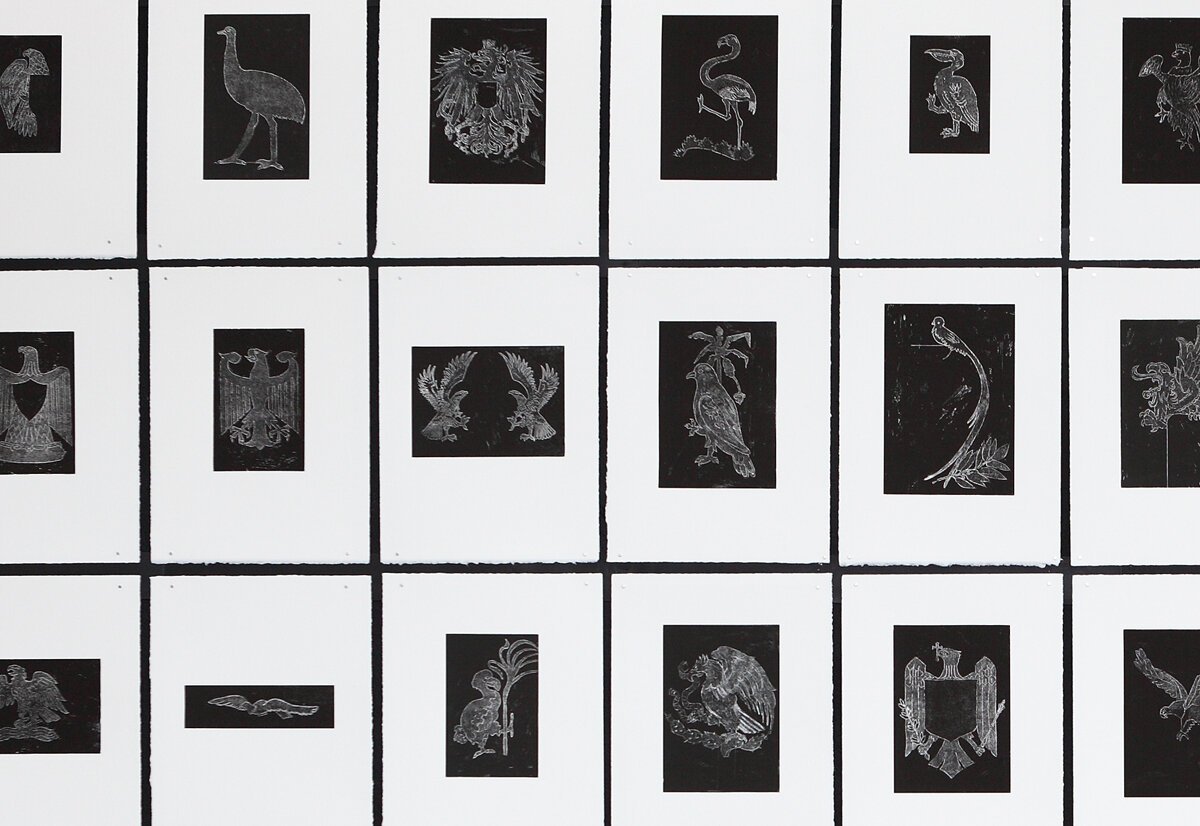

To create the series entitled Amateur Watching at Passport Control, the artist studied all 195 passports currently in circulation worldwide. She dissected the symbolism of the coats of arms featured on the covers, and identified four major categories: plants and trees, birds, big cats and weapons. From Lebanon’s cedar to Mauritius’ dodo, to Georgia’s lions and East Timor’s AK 47, the four works in the series, Amateur Bird Watching at Passport Control, Amateur Cat Watching at Passport Control, Amateur Flora Watching at Passport Control and Amateur Arsenal Watching at Passport Control (2016-2019), bring to life this curious intersection between nationalism and nature.

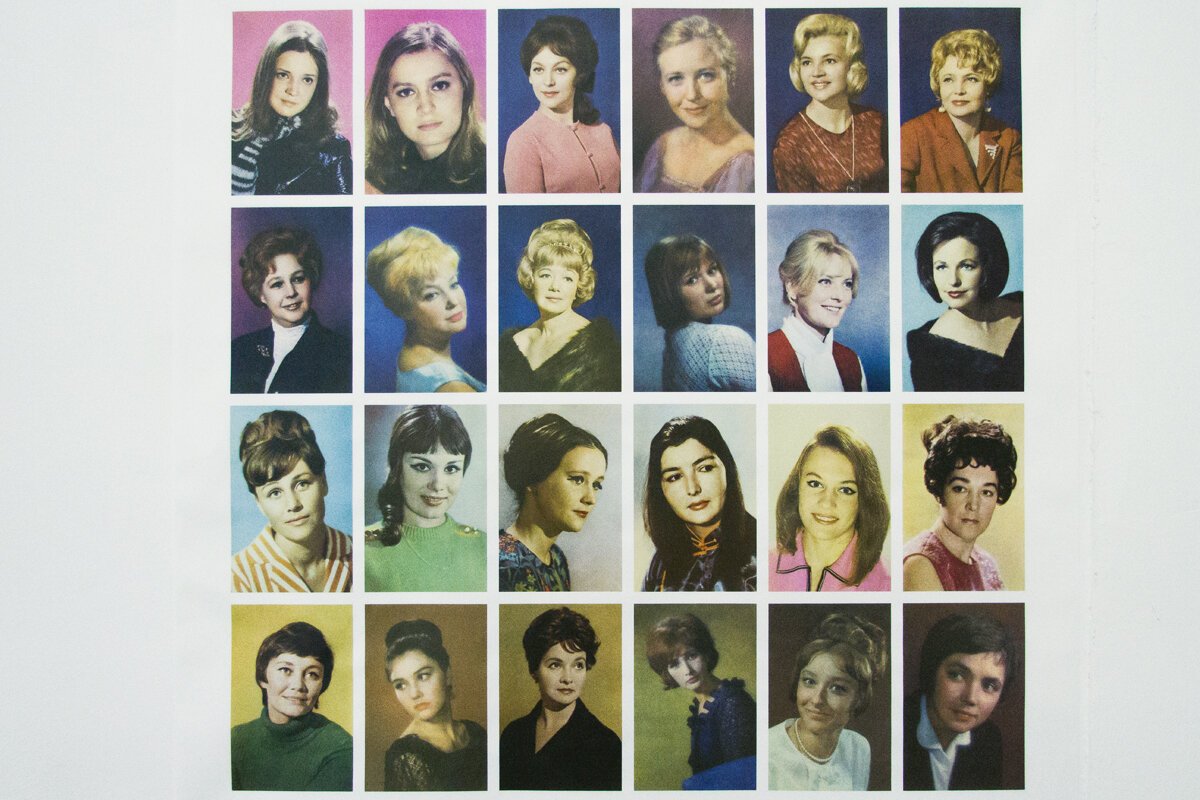

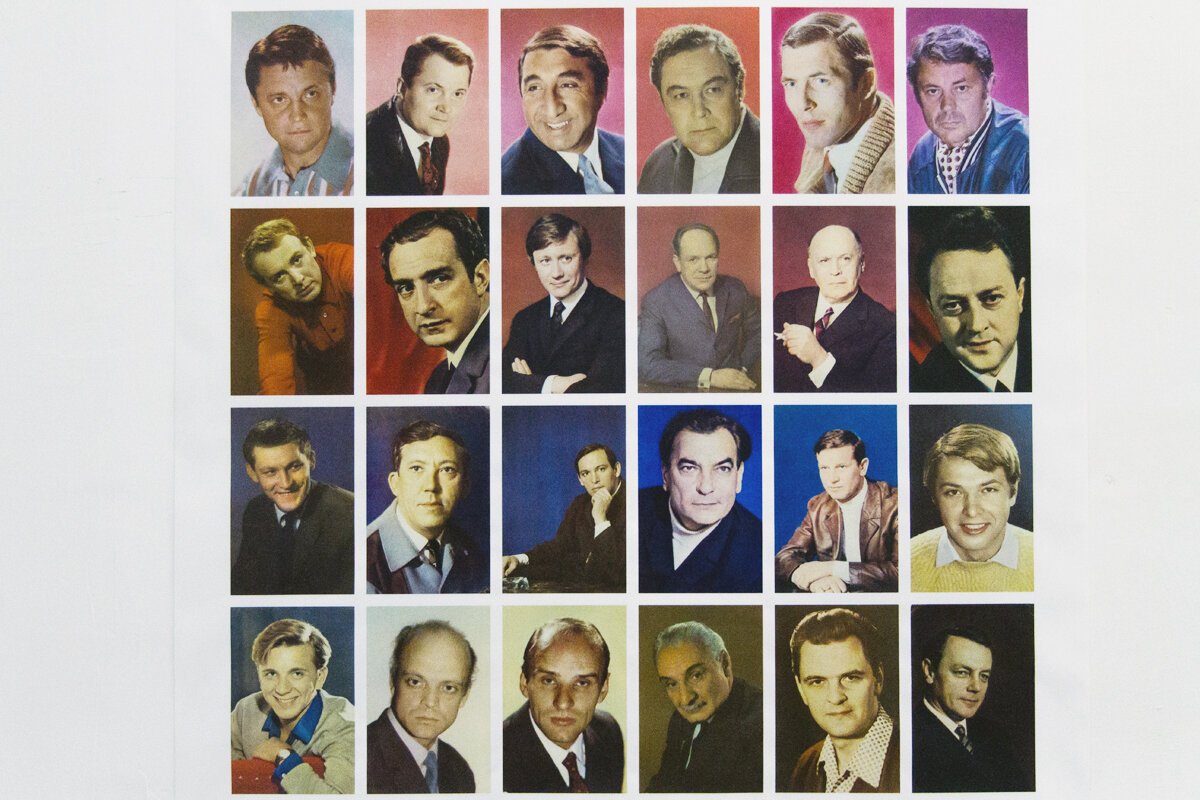

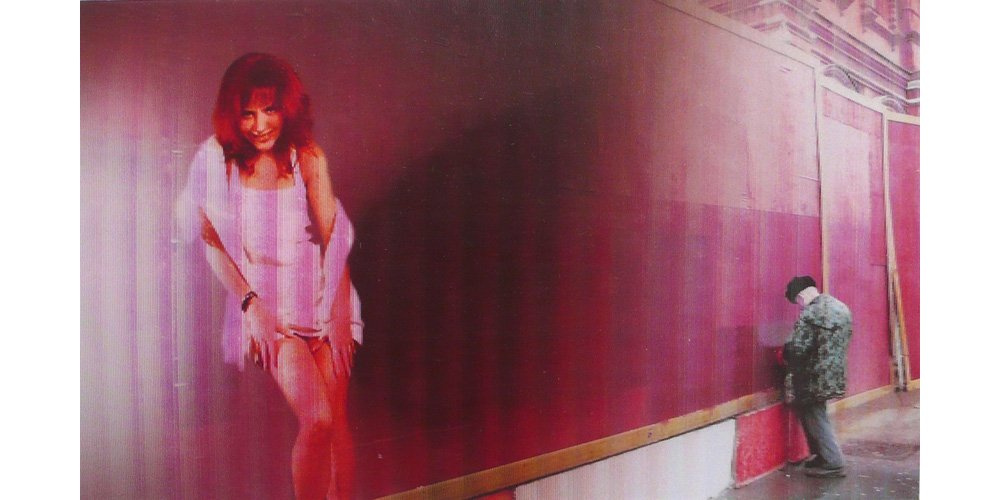

The exhibition also includes the works: My Soviet Childhood, He and My Soviet Childhood, She,2018. Bliumis created them together with her long time collaborator, Jeff Bliumis. The diptych comprises a collection of postcards of Soviet movie stars from the late 1960s through to the 1980s that he built up during his childhood. The artist says “the series is dedicated to all Soviet-era children who collected stamps, postcards, pins, cigarette and match boxes, soda bottles, candy wraps, juice box stickers” during that time. There is an implied association between identifying the symbols on modern passport covers and the curious eye that encouraged the collection of Soviet movie star postcards. Having past experience of this common childhood pleasure, of creating and curating collections of day-to-day objects, is essential in understanding both Most of Us Are and Amateur Watching at Passport Control series.

In My Soviet Childhood, He and She, the artists are trying to create a portrait of the most typical Soviet-era movie star. But there is a reverse process underway in Amateur Watching at Passport Control. Alina Bliumis is grasping the bigger picture of different coats of arms and dissecting them into their visual parts.

The exhibition is made possible by the generous support of the Trust for Mutual Understanding and the Franklin Furnace, NY

Alina Bliumis ON THE LAND OF EAGLES Galerie Anne de Villepoix, Paris, France September 14 - October 26, 2019

Alina Bliumis’ exhibition, On the Land of Eagles, voyages through global national symbols and identities. The Poems Without Borders series features the world’s tourism slogans in patterned rhymes. Amateur Bird Watching at Passport Control unlocks symbolic imagery from passport covers. The artist traces global territories in the allegorical Maps Unleashed drawings, and portrays national animal symbols in the Nature of Nations series.

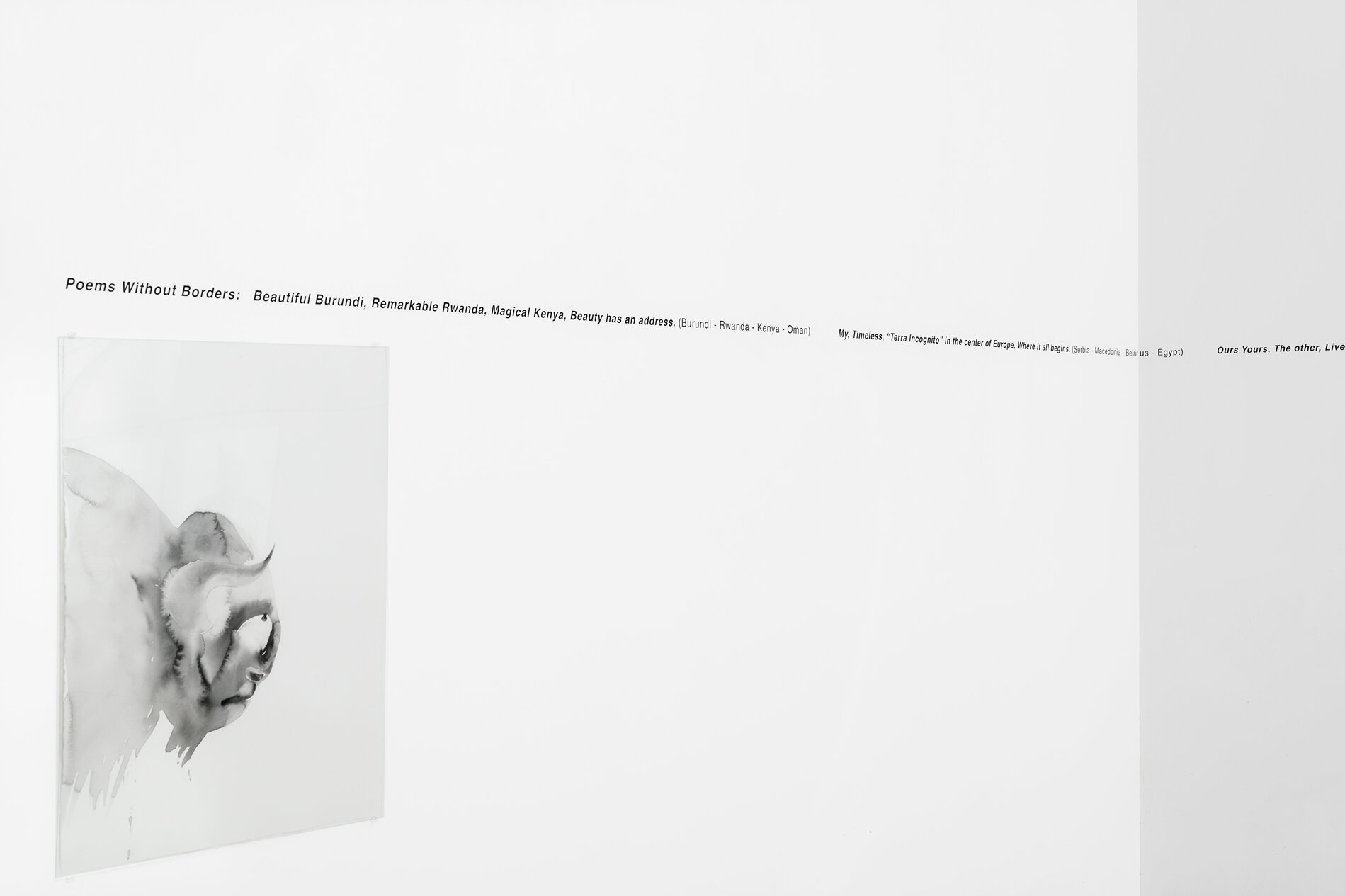

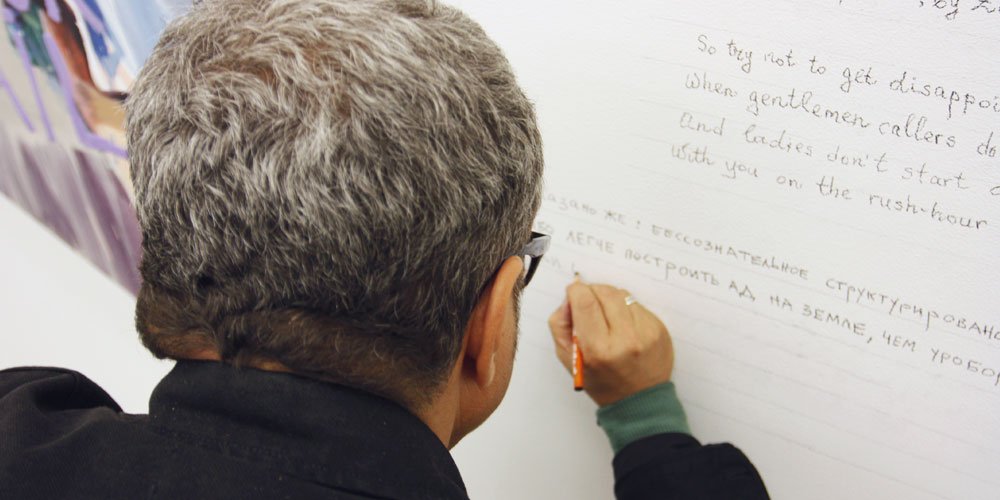

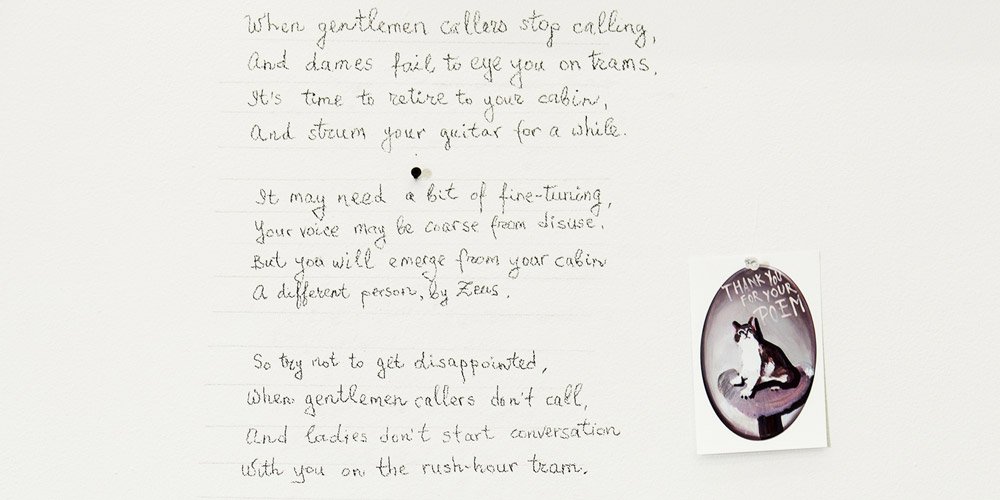

“I feel Slovenia, I need Spain, Fiji Me, Cameroon is back.” Tourism slogans market countries to an expanding industry fueled by low-cost no-frills airlines. Abstract yet suggestive taglines allow foreigners to dream up their own ideas about the countries they want to visit. The series Poems Without Borders (2018-2019) arranges official national tourism slogans of forty-eight nations into sixteen poems. For this exhibition, the text-based piece is placed directly on the wall in one straight line that wraps around the gallery space.

Tourism and migration are the most significant manifestations of globalization. While economic, political and environmental migrants are routinely blocked at the border, tourists are ceaselessly wooed on various media and advertising platforms. While countries sculpt their national identities to make themselves more appealing to visitors, they use ethnic and cultural definitions to reinforce laws limiting migration.

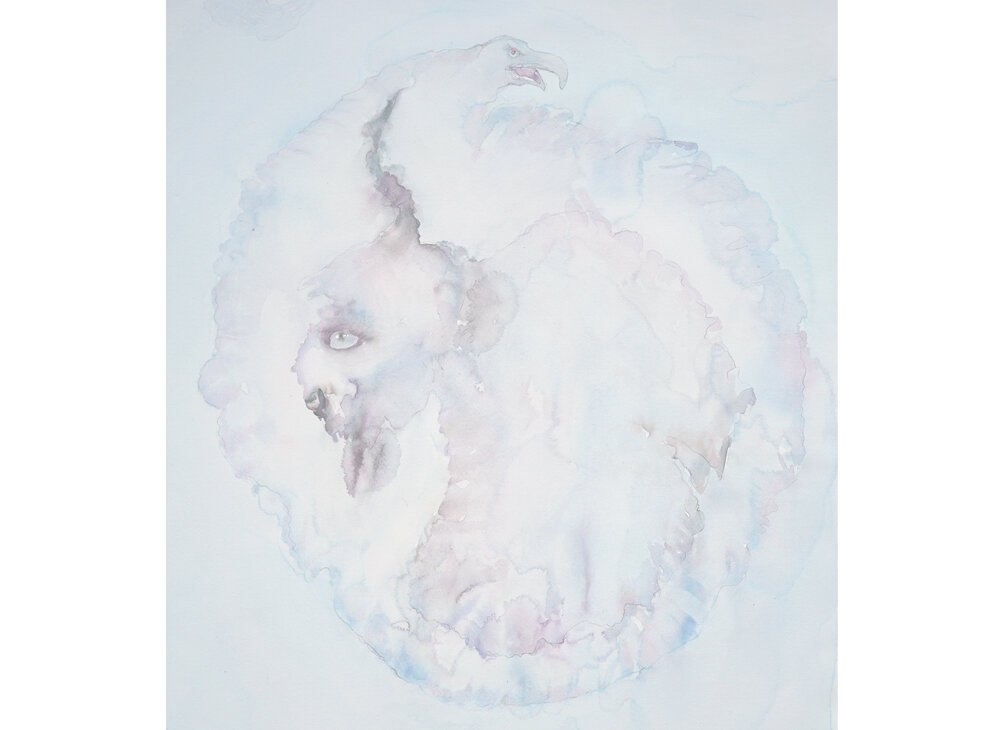

“Free as a bird” we definitely are not. Yet ironically there are fifty bird symbols incorporated into the coats of arms depicted on the passport covers of forty-three nations. The Amateur Bird Watching at Passport Control series (2016-2017) presents forty-three works on paper. From eagles to doves, from Albania to Tonga, Bliumis studied all existing passport covers – 195 in total -- looking for birds in order to free them from their national context. She traced each bird, true to its source, with a focus on the species’ characteristics. The birds at the intersection of nation and nature include: the famous one-legged pose of a flamingo (Bahamas), a vulture in a gliding flight (Mali), an extinct flightless dodo (Mauritius), a rooster with an axe (Kenya) and a mythological creature that is part woman and part bird known as a Harpy (Liechtenstein).

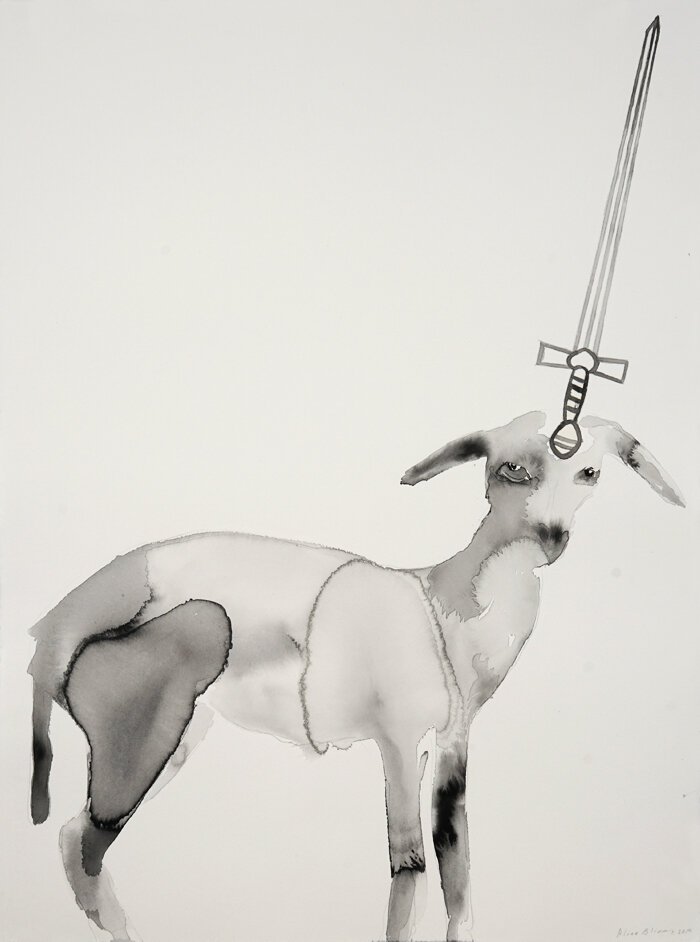

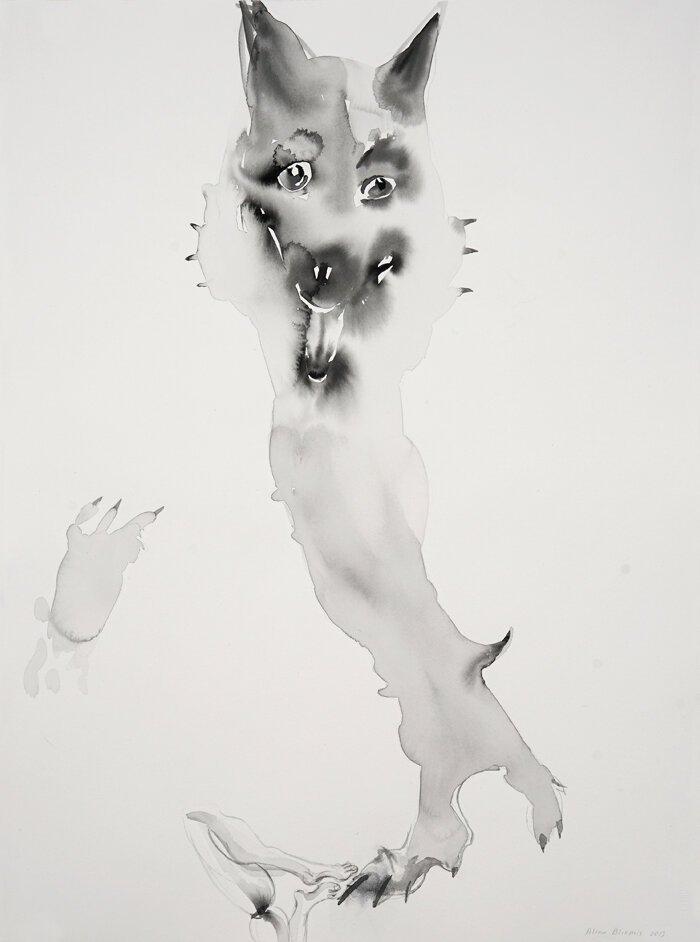

Birds are not the only animals that nations use to symbolize themselves—a brown bear, a Fennec fox, an Apennine Wolf, a Barbary Macaque, a Marten or a goat are all official national animals. Nature of Nations (2019) is a series of watercolor portraits inspired by official national animals, heraldic design elements, geographical borders, folk fables, and stereotypes. The resulting images portray: A bird of prey, the bald eagle, freed from the USA coat of arms with a halo made of two olive branches is staring at the viewer, its claw is free of arrows. A seductive double-headed rooster of France is flirting with the audience. An outraged bear with wings is a combination of two symbols, the bear of the Soviet Union and the double-headed eagle of contemporary Russia. A goat of Iraq is crowned with a sword-shaped horn.

The series Nations Unleashed (2018-2019) is inspired by the historical tradition of satirical maps, which employ animal symbolism and stereotypes to convey biting political critique and/or to cover up human actions in certain political theaters. The series comprises watercolor and pencil drawings on paper. Delicately toned washes of blue surround loosely sketched landmasses populated by an array of diverse animals, each representing a critical political interest. Bliumis’ interpretations range from the literal – as in the American bald eagle – to the fanciful – as in a two-headed Scandinavian lion. What these maps lack in geographic accuracy is made up in thorough doses of imagination and humor, leaving further interpretation open to the viewer.

All four series in the exhibition investigate the formation of national identity, its historical and geographical roots and its ambitions in global geopolitics. National symbols often reflect national interests, but imagine for a moment if, as the myth goes, the U.S. Congress had conceded to Benjamin Franklin. For instance, he might have chosen the wild turkey as the national bird, instead of the bald eagle. Would the country’s domestic policies and international interests have unfolded differently?

COSMOPOLITICS, COMRADESHIP, AND THE COMMONS, Shelter festival, Helsinki, Finland Curated by Corina L. Apostol, Ksenia Yurkova and Anastasia Vepreva June 7-9, 2019

EXPLORING ENVIRONMENTAL PHILOSOPHY, ECOFEMINISM, QUEER ECOLOGY AND ECOLOGICAL RESILIENCE THROUGH KEY PROJECTS BY INTERNATIONAL ARTISTS, SOME ON VIEW FOR THE FIRST TIME IN FINLAND.

This year the festival will consider some of the most pressing issues of our times under the conceptual umbrella of eco-feminism, queer ecology, environmental philosophy, and ecological resilience. Entitled "Cosmopolitics, Comradeship, and the Commons" the 2019 festival-laboratory will feature diverse works including performance, installation art, poetry, film screenings, as well as discussions, artistic research, and an online publication bringing together artists and cultural practitioners from the Scandinavian countries, the Baltic Region, Eastern Europe, Russia, and beyond. Drawing on Isabelle Stengers' concept of "Cosmopolitics," where diverse stories, perspectives, and practices connect to lay the foundation for new strategies and radical possibilities, the Festival will act as a temporary commons for diverse approaches to the ecological crisis and its economic, social, and cultural affects and effects.

The festival invited artists, activists, educators, musicians, and all cultural producers in the greater Helsinki area and beyond to propose projects at the intersection of deep ecology, climate resilience, environmental philosophy, ecofeminism, and socially engaged practice.

Russian performative and experimental musical collective Techno-Poetry (Roman Osminkin, Anton Komandirov, Marina Shamova); Sweden-based art-collective HAMNEN (artist and filmmaker Klængur Gunnarsson; artist Maria Safronova Wahlström; artist Josef Mellergård; award-winning filmmaker, journalist and writer Johannes Wahlström); ex-academic turned video essayist Natalie Wynn based in the US; artist, activist and filmmaker Oto Hudec based in Slovakia; collaborating Romanian artists Anca Benera and Arnold Estefan; artist and filmmaker Oliver Ressler based in Austria; curator and art critic Raluca Voinea based in Romania; Sami artist, author and journalist Máret Ánne Sara based in Norway; Polish poetic choreographer, performance maker, curator of experiences Valentine Tanz/ Vala Tomasz Foltyn based in Denmark; UK-based art historians and curators Maja and Reuben Fowkes; and Belarusian-American artist Alina Bliumis are amongst this year's participants.

More than 20 participating artists, musicians, curators and theoreticians were selected via an international open call: Anna Sopova and Antanas Jatsinevichys (Russia); Inês Tartaruga Água (Portugal); Ipek Burçak (Turkey); Collective HEXY (Justyna Jakóbowska, Roksana Kularska-Król, Justyna Stopnicka) (Poland); Lea Roth (Germany); Laurene Bois-Mariage (Finland); Maria Veits (Russia/ Israel); Andréa Stanislav (US); Axel Straschnoy (Finland); Vo Ezn (Georgia); Mathilda Franzén (Sweden); Natalia Skobeeva (Russia/ Belgium); Rabota (Marika Krasina & Anton Kryvulia) (Germany/ Belarus); Roman Golovko (Russia); Silvia Amancei and Bogdan Armanu (Romania); Susi Disorder (United Kingdom); Saša Nemec (Slovenia/ Finland); Taisia Korotkova (Russia); Valerii Shevchenko (Russia); Vera Kavaleuskaya (Finland/ Belarus); Verneri Salonen (Finland); zh v yu (Natasha Zhukova, Katya Volkova, Dasha Yurychuk) (Russia).

The festival also presents the Suoja/Shelter Reader, a compilation of educational materials in conversation with the performances, art installations, films, music, and discussions taking place throughout the festival. The Reader has been put together by the festival curator and organizers. The reader also contains a themed glossary of terms.

Suoja/ Shelter is held at the Space for Free Arts under the Auspices of the University of the Arts Helsinki (UNIARTS). It is supported by the City of Helsinki, the Finnish Cultural Foundation (SKR), and the Arts Promotion Center Finland ( TAIKE). Spanning three full days of programming between June 7-9 at the public shelter turned into the Space For Free Arts/ Vapaan Taiteen Tila in the Sörnäinen neighbourhood of Finland's capital, the festival is free and open to the public. It is curated by Corina L. Apostol, an independent curator and writer based in New York/US and Constanța/Romania, together with artist and curator Ksenia Yurkova (Finland/ Russia) and artist and curator Anastasia Vepreva (Russia).

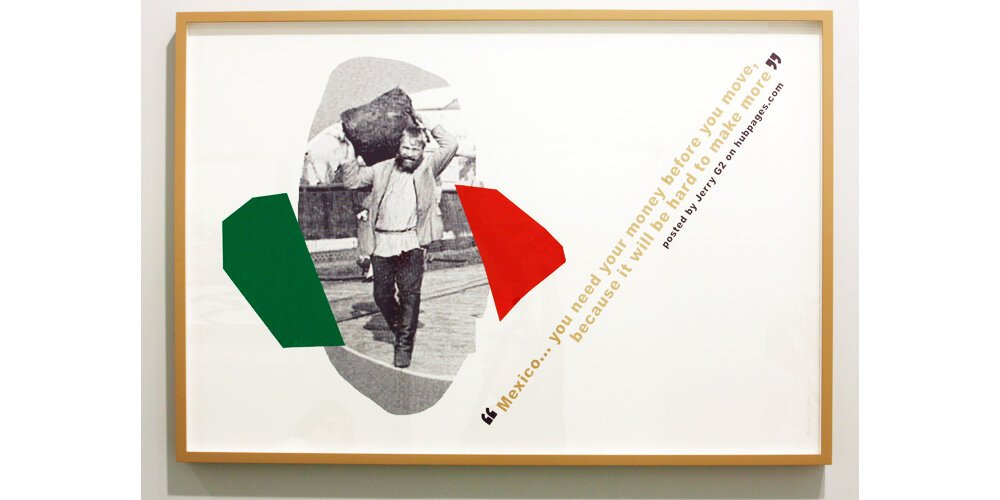

Alina and Jeff Bliumis WHICH COUNTRY IS THE BEST TO MOVE TO? Person Grata, the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration and the MAC VAL, Curators Anne-Laure Flacelière and Isabelle Renard

Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration

16 October 2018 – 20 January 2019

Co-curated by Anne-Laure Flacelière, MAC VAL collection Study and Development Officer and Isabelle Renard, Collections and Exhibitions Director at the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration

With works by Bertille Bak, Dominique Blais, Alina Bliumis, Jeff Bliumis, Halida Boughriet, Kyungwoo Chun, Philippe Cognée, Pascale Consigny, Hamid Debarrah, Latifa Echakhch, Eléonore False, Claire Fontaine, Laura Henno, Pierre Huyghe, Bertrand Lamarche, Xie Lei, Lahouari Mohammed Bakir, Moataz Nasr, Eva Nielsen, Gina Pane, Laure Prouvost, Enrique Ramirez, Judit Reigl, Anri Sala, Sarkis, Zineb Sedira, Bruno Serralongue, Chiharu Shiota, Société Réaliste, Dan Stockholm, Barthélémy Toguo...

Welcome ! Festival

6 October – 11 November 2018

Programming: Stéphane Malfettes

Under the eyes of philosophers Fabienne Brugère and Guillaume Le Blanc, authors of La fin de l’hospitalité, this two-fold exhibition will be complemented by a cultural programming: Welcome! at the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration (6 October-11 November 2018) and Attention fragile at the MAC VAL (30 November, 1 and 2 December 2018).

MAC VAL – Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne

16 October 2018 – 24February 2019

Curated by Ingrid Jurzak, MAC VAL Collection Study and Management Officer

With works by Eduardo Arroyo, Marcos Avila Forero, Bertille Bak, Richard Baquié, Taysir Batniji, Ben, Bruno Boudjelal, Mark Brusse, Pierre Buraglio, Mircea Cantor, Étienne Chambaud, Kyungwoo Chun, Philippe Cognée, Delphine Coindet, Julien Discrit, Thierry Fontaine, Jochen Gerz, Ghazel, Marie-Ange Guilleminot, Mona Hatoum, Éric Hattan, Laura Henno, Emily Jacir, Yeondoo Jung, Bouchra Khalili, Kimsooja, Claude Lévêque, Lahouari Mohammed Bakir, Lucy Orta, Bernard Pagès, Yan Pei-Ming, Cécile Paris, Mathieu Pernot, Jacqueline Salmon, Bruno Serralongue, Esther Shalev-Gerz, Société Réaliste, Djamel Tatah, Barthélémy Toguo, Patrick Tosani, Sabine Weiss...

Attention fragile

Festival-Rencontre, 30 November, 1 and 2 December 2018

Programming: Stéphanie Airaud - Thibault Capéran

The Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration and the MAC VAL- Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne are collaborating to present a project questioning the notion of hospitality through the prism of contemporary creation. Together, the two institutions- a social museum that value contemporary creation and a contemporary art museum that tackles social issues- are happy to present “Persona grata”, an exhibition organized over the two locations with a rich cultural programming: an occasion for artists to explore all the dimensions of what constitutes or corrodes the notions of hospitality and alterity through their own vision and sensitivity.

The acceleration of migratory flows and the growing place these issues occupy in the public debate increasingly question the foundations of our societies. On one hand, camps and walls mushroom and confirm the irreversible setback of our hospitality duty, while on the other, citizen involvement grows to help, support and welcome migrants. Is the answer of today’s harsh society to bring emergency assistance rather than implement long-term and effective hospitality policies?

In this context and from the collections of both museums, this artistic partnership aims at highlighting a contemporary creation that reflects today’s world as well as tackling these issues from the point of view of the many artists who have explored the theme of hospitality over the last years.

The exhibition will provide a platform for artists to share their analyses, critics and feelings toward national fold, behaviors of rejection and revolt. These artistic testimonies will help us think these questions through and look at ourselves yet without any moralistic judgment.

Through this unique and engaged partnership project, the Musée national de l’histoire de l’immigration and the MAC VAL look to raise awareness, foster reflection and debate, and call our certitudes into question. Although central, the issues related to migratory flows do not cross out other neglected –and little known- forms of hospitality toward helpless and weakened populations. The exhibition will bring forth proposals around community life, care for others, the necessity of nursing homes, public health-care and hospitality centers held in a spirit of attentiveness, kindness and sharing we should rehabilitate.

Stamatina Gregory NEVER BEEN TO NAURU, Political Animals, Aperto Raum, Berlin

What is a global citizen? In the absence of a transnationally enforceable set of laws or doctrines on human rights, ecological preservation, or other interests of humanity, what remains is a set of ideas, historical and contemporary, on what this term—global citizenship—could mean. In 2005, the World Values Survey—a global research project providing data on socio-cultural and political change—included for the first time the statement “I see myself as a world citizen,” in its polling of almost 54 countries on subjects including religion, national identity, and well-being. (For the record, most of those polled in 2005 agreed.) Over the past decade (one in which globalization and its discontents have been only recently the subject of major electoral rifts), global citizenship has come to be defined in various ways, including interconnectedness, social and environmental justice, empathy, and cultural understanding.

Although there are now plenty of innovative curricula and inspired mission statements around this idea, there is little consensus on how and why people come to see themselves as sharing some wider identity. But one could extrapolate one possible shared idea: on some levels and in some ways, however banal or incidental, we are more alike than different. Regardless of mass educational inequality, we generally agree that the earth is round. Despite our nuanced views on the finer points of the government’s regulation of the free market, or the degree to which extreme wealth is rightfully earned, we mostly agree that capitalism’s effects are evident (the poor get poorer). We have statistically dominant favorite colors and favorite Disney moments.

If some of this sounds like a sappy commercial, that’s no accident. “Most Of Us Are” (2018) takes as its material recent years of both statistic demographic research and global opinion polling—practices that originated after the Depression, when decreased funding for advertising created a demand for more informed knowledge about domestic (and eventually, international) consumer demographics. Bliumis’s work references several of the hundreds of worldwide polls undertaken recently, including regular Bible reading (tracked by Gallup since 1992); acknowl- edgment of climate change (Gallup, 2007); belief that capitalism results in growing inequality (YouGov, 2017); and the belief in extraplanetary life (Glocalities, 2017). In each work on canvas, a global everyperson, metaphorically sketched in broad categorical strokes, is accompanied by the literal sketches of figures, resembling those found in instructional books on life drawing, which present “average” human figures and the basic shapes of their rendering – cubes, triangles, oblongs, long and arced lines. Unique physiognomies, race, disability, and other forms of dif- ference evaporate in these dual portraits, each a simultaneously tender and absurdist poem of statistical appropriation.

On the one hand, no citizen of the world cobbled together from shared demographic data truly exists. “Most of Us Are #1” makes this point, tongue in cheek, noting “most of us are named Mohammed, last name Lee.” A few Mohammed Lees undoubtedly exist in the world—but clearly under a radically different set of intercultural circumstances than the vast majority of those that share either their surname or first name. (A well-known line from the American TV sitcom The Big Bang Theory, in which a character, angling for a “statistical edge” in his answer to a trivia question about a famous astronaut, shouts the name “Mohammed Lee,” has become a contemporary punchline.) “Most of Us Are” playfully follows this tension, moving between the broad strokes which sketch an imaginary global citizen (at least, an imaginary product of a narrow set of offered choices, opinions, and affiliations), and a citizen for whom broadly constructed categories of identity may never (or could never) apply.

Whoever a global citizen might be, most of us would agree: freedom of movement is en- demic to their self-perception. (The mere ability to respond to a poll, signaling some degree of enfranchisement, might be another indicator.) What “Most Of Us Are #2” states is true: most of us have “never been to Nauru.” But the tiny state in Oceania is a microcosm for the global forces that shape our opinions and affiliations, as well as our seemingly immutable identifying data. Nauru is like many other parts of the globe in its history of colonization, military base use, ecological devastation due to phosphorous mining, turning the island into a hollow shell rimmed by coconut palms: an invasive species that has wiped out any remaining indigenous flora. With its natural resources depleted, and its one-time economic boom turned to seemingly permanent bust, the Nauruan government instituted liberal banking policies, becoming an easy access point for international money-laundering operations. Most recently, Nauru has entered into the rapidly expanding business of offshore refugee detention, partnering with the Australian government to keep asylum seekers, including children, in conditions of imprisonment lasting years: an indefinite “processing” aimed to quell anti-immigrant sentiment. Residents of similar places in the world, in which neither practical national citizenship nor any sense of global affinity are able to exist, are growing.

With this in mind, perhaps the better question is not who is the global citizen, but where is the global citizen? Or rather, where and how does this idea exist? According to a recent poll by GlobeScan, citizens of emerging economies, including China, Peru, and India, are most likely to identify as citizens of the world—more strongly than their sense of belonging to their own country. But, perhaps unsurprisingly among citizens of Germany, the US, and Russia a sense of nationalism has been rising. “Most Of Us Are,” deceptively simple in form, draws the faintest lines of the structures of power that construct our entire subjectivity. In this speculative space, a gentle call, a lyric appeal to look beyond a rapidly encroaching, perilous nativism.

Adam Kleinman PLUCKED, Political Animals, Apero Raum, Berlin

For my own part I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character.

-- Benjamin Franklin

When thinking of “Political Animals,” the eponymous title and subject of Alina Bliumis’s exhibition on the iconography and narrative tropes nations use to imagine their communities, I thought, at first, of two things: Aristotle, and my passport. The reasons for the former are bound to the latter, and vice versa; Aristotle coined the term in his Politics, while my passport is proof of my own citizenship. Yet that’s all very abstract, if I were to imagine my passport itself, I’d think of its size, its blue color, and that heraldic image of a bald eagle bearing a shield whilst clenching a set of 13 arrows in one talon, and an olive branch in the other on its cover. Yes, it’s an American Passport. Is there a bird on yours?

Sorry, I shouldn’t have asked you to imagine that, it was rude of me. I have no idea where you’re from, and, logically speaking, it’s a safe bet that people from various nationalities would be reading this—this catalog is published in two tongues after all. Fortunately, Political Animals includes Bliumis’ rueful series of relief etchings on paper entitled Amateur Bird Watching at Passport Control, 2016-17, which abstracts fanciful bird imagery sourced from 43 different passport covers; if you’re up for a hunt, you might find a feathered friend there, or in these very pages. Interpersonally though, there is no way I could pretend to address each and every one of you directly and individually by talking about your eagle… or was it flamingo? Instead, let’s all share another image together; it’s pretty famous, so I hope you’ll be able to fix it: please, for a second, imagine the Oval Office of the White House.

Yes, it’s egg shaped, and the President of the US sits there; oh, god no, please don’t think of the unmentionable current one, instead let’s just think of that iconic desk. You know the one, its wooden, and clunky, and has the same motif, more or less, as my passport on its front. But wait, something is different! On my passport the bird faces the olive branch, a typical symbol of peace, whilst the image on the desk faces the arrows of war. So, which one is it; dose the bird seek war, or does it look toward peace?

The carving on the desk dates from the early 1940s, and the bird’s head was typically turned to face the arrows at that time. In 1945, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9646, which permanently fixed the eagle’s gaze toward the olive branch as a sign of the county’s dedication to harmony following WWII. Although the figure bares the Latin motto, E pluribus unum (from many, one), Si vis pacem, para bellum (If you want peace, prepare for war) serves as a better metaphor for the intrinsic paradox of this emblem—and is a clear mirror of the history of American relations from (at least) the gunboat diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt’s Big Stick Ideology—wherein pressure was applied to diplomatic negotiations through the ever present threat of naval force—all the way through the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction—a defense strategy between the United States and the Soviet Union which would see each nation build ever larger nuclear arsenals as a form of deterrence; the logic went as follows: if one nation were to initiate a pre-emptive nuclear attack, the other could guarantee an equal retaliatory strike. In this standoff, neither party could advance or withdraw safely, and thus the superpowers settled into a geopolitical equilibrium so bizarre they had to invent a term for that too, the Cold War. As that situation played out internally, the US military establishment found a workaround when their projects couldn’t get the green light during the administration of Dwight D. Eisenhower.

To make a long story short, dubious documents would be “leaked” to the press, which proposed that the Soviet Union was making secret weapons that the United States did not process. The most infamous of which was the so-called “bomber gap,” which alleged that the Soviets built a mythical fleet of long-range jet bombers totaling around 2,500. Whether this was true or not, an alarmed public believed the hype and called on its elected official, the President, to do something about it. In response, Eisenhower fast tracked the U-2 spy plane, which was designed to assess how many bombers the Soviets had—turns out it was only 20—while the US Air Force ordered 2,750 new bombers of its own. Following this media ploy, new and greater threats were created following the same model—the “missile gap,” for example, simply exchanged fictive bombers for fictive intercontinental ballistic missiles following the launch of Sputnik. This fearmongering dynamic continues to affect US politics; in order to not look “weak,” politicians, generally Republicans, often trumpet defense spending over domestic issues that might better serve the people. These politicians are known as “hawks,” but let’s turn strategy round in a truly Machiavellian manner: can the people by pacified, and thus ruled over more easily, by cynically scaring them into compliance through the manufacture of an existential enemy “other”?

In 1984, the sitting President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, was up for re-election, and his campaign released a slew of negative television commercials; the most famous of which features a grizzly bear roaming around on a mountain top that comes to a stop in front of an everyman character. A coded message in voice over implies that the US requires a strong leader that could stand up to that “bear” should it attack. The ad doubled down on the jingoism Reagan had banked on in his 1980 electoral victory, particularly the slogan that his administration would “seek peace through strength,” and his own escalation of the Cold War arms race during his first term. Even though the Soviet Union, or the “Evil Empire” as Reagan had nicknamed it, was then on the brink of collapsing under its own weight, this narrative helped Reagan sweep 49 of 50 states in the arguably greatest presidential election landslide in American history. Teasingly self-aware of its manipulation, the ad curiously concludes with the line “if there is a bear.” Like the bomber gap, or the missile gap, the predator analogy might simply be a vehicle open to various referents as long as the “us” verse “them” formulation holds—that is, if there even is a “them.”

By way of satire, this operation is dished out ad libitum by Bliumis in her If There Is A Bear series, 2018, which appropriates the Reagan advert transcript, but then replaces the titular bear with other animals that each imply other nationalities respectively, i.e. “There is a Panda” (read: China). Collected and juxtaposed together, this set breaks the message down into its pure rhetorical form to demonstrate that it, like “policy by press release,” is simply a form of style over substance.

As noted, the exhibition’s title, Political Animals, is borrowed from Aristotle; however, instead of meaning, as Aristotle did, that we build society by practicing good social relation with one another in organized establishments called cities (polis), Bliumis mockingly takes this expression at face value through a comic, yet productive form of literal mistranslation by focusing the use of birds, bears, and so forth, in political theater. Regardless of biology, states divide the world into two types of fictive persons: their citizenry, and everyone else. So as to keep this exclusionary set-up under control we had to invited something bestial, but sadly, something all too human: the police. Although boarders are themselves fictive, try to cross one without your identity papers. But really, what is identity anyways? I mean if your documents are expired, does your name do so well? Or perhaps, your height and eye color vanish in a puff of smoke, poof!

Identity is derived from the Latin word for “sameness,” idem. In the line of questioning above, the sameness sought is simply one of physical continuity, and not some idea of shared desire, history, or similar narratives that actually lend us our humanity. In addition to musing on birds and bears, Political Animals hosts a series that queries our species directly. Entitled Most Of Us Are, 2018, this set of ink and graphite pencil works on canvas link geometric construction drawings of neutral bodies next to a list of curious, reductive, and generally illogical data points, i.e., most of us are born at 8am—I wasn’t, were you? Like her other jibes, Blimuis’ principle here is the same: take a form, repeat its permutations to a point of absurdity, and ultimately lay bare the totalizing bureaucracy of procedure.

Thinking back to my passport, maybe, E plurius unum (out of many, one), isn’t so bad after all; while it is meant as a metaphor for the total population blending into one uniform body, it’s based on a line from the poet Virgil when discussing how to make an ancient form of pesto by combining cheese and herbs in a single pot. The use of this motto comes from the very early days of my republic, and I wonder if the framers of the Constitution remembered this quasi-irony when they paradoxically used the royal “we” to start that document. Who is to say, but we’ve never quite figured out just who we are. Instead of checking off our associations, let’s just discuss the majesty of birds over a nice turkey dinner.

Boris Groys WHAT DO THE BIRDS DREAM ABOUT? Political Animals, Apero Raum, Berlin

When we speak about globalization we mostly mean the global circulation of information, money and commodities. However, long before this circulation started animals, birds and insects were circulating around the world – and they still are. Migration of birds and animals preceded the migration of men. At the same time not all the animals migrate. Some of them are local – and parts of local ecologies. That is why migration of animals and other living organisms, such as viruses and microbes, is seen as dangerous for the ecological balance in certain regions. Now, the analogy with the human migration is obvious. Often enough it is also seen as a negative factor destroying the ecological balance of certain national states.

Alina Bliumis came to the USA from Belarus. One of the persistent topics of her art is a reflection on the processes of accommodation and integration in which everyone with a similar background is unavoidably involved. The tone of this reflection is far from being dictated by personal ressentiment or protest. Rather, her attention is drawn by the absurdities of the processes themselves. Her recent projects Amateur Bird Watching at the Passport Control and Political Animals deal with the images of animals and birds that serve as symbols for different national states and thus put on the official documents, including passports, of their citizens. There is this standard expression: free as a bird. Speaking about the freedom of birds we mean, of course, the migrating birds that high in the sky cross all the national borders – the freedom which the planes, for example, do not have.

However, the birds which images we find in our passports are not migrating

birds. Mostly, they are birds of prey – like eagles, for example. In this respect they are similar to the political animals – lions or bears. The eagles do not migrate – they are circling in the air and controlling their territory. They are machines of surveillance. They look for a prey – and catch it. So it is clear enough why so many states have chosen the eagle as its symbol. Of course, there are also some more peaceful examples. But the common characteristic of all these birds is the fact that they are local – be it a pelican from Barbados or a parrot from Dominica. All these birds are prisoners of their territories. Do they ever dream to become free, to migrate, to visit different countries – and not only to draw always the same circles over the same territory? We do not know it. But if the birds have these dreams it is the citizens of the states that have images of these birds in their passports who realize these dreams – at least in symbolic terms. Thus, even if a parrot remains on Dominica and a pelican - on the Barbados the passports with their images have a chance to be checked at the airports all around the world. Whatever can be said about the migrants one thing is sure: they realize their birds’ dream of flying.

.

Alina Bliumis, POLITICAL ANIMALS Aperto Raum, Berlin 13 September - 22 October 2018

Aperto Raum is proud to present Political Animals by Alina Bliumis, her first solo exhibition In Germany. The title of the exhibition references Aristotle's term in his Politics. "However, instead of meaning, as Aristotle did, that we build society by practicing good social relations in organized establishments called cities (polis), Bliumis mockingly takes this expression at face value through a comic, yet productive form of literal mistranslation by focusing the use of birds, bears, and so forth, in political theater. Regardless of biology, states divide the world into two types of fictive persons: their citizenry, and everyone else. So as to keep this exclusionary set-up under control we had to invite something bestial, but sadly, something all too human: the police. Although borders are themselves fictive, try to cross one without your identity papers. But really, what is identity anyways? I mean if your documents are expired, does your name do so well? Or perhaps, your height and eye color vanish in a puff of smoke, poof!” - excerpt from Adam Kleinman, "Plucked," exhibition catalogue

Political Animals presents four series: Amateur Bird Watching at Passport Control, If There Is A Bear, Political Animals and Most Of Us Are. Amateur Bird Watching at Passport Control focuses on the birds that are featured on passport covers from countries around the world. From eagles to doves, from Albania to Tonga, this series explores the intersection of nation and nature. The series If There Is A Bear is inspired by the TV ad titled The Bear, created by Hal Riney for the 1984 U.S. presidential campaign of Republican candidate Ronald Reagan. This example of the Cold War narrative make us aware that using animal imagery for the purpose of politics is not merely an aesthetic choice, but in fact a political strategy. While Political Animals is blurring the boundaries between the human and the animal, Most of Us Are is a study of the human species based on statistics of the “most typical” person worldwide.

“The Deadnet letters” project: letters to artists from a digital afterlife Tanya Zamirovskaya, 2022

from: _____

to: ________

subject: just name it after me / a correction notice

I know you won’t reply. You don’t believe me, but you demand the whole world to believe you – all of you are the same. The information you obtained is sacred to you – but the information I am cancels yours. So I am just fake news to you.

As you see, I can use your language if it’s necessary – and it’s really necessary, since I speak about my life, which you all deny for the name of conditional truth. My language is not a perfect weapon in a war your speech has declared to my existence – but since my existence is more important to me than all types of speech and species, I – as an endangered species – demand a correction!

I already emailed you, demanding a correction, I tried, I cried, I texted your managing editor, I wrote to your publisher – all of them demanded a confirmation – confirmation of what? That I’m alive? How can you prove that you’re alive? To prove death – yes, this is easy, there are rules and rituals, like cat’s eye syndrome (squeeze an eye with your fingers – it will become cozy, cat-like, with a dark slit), those special shades of farewell breathing, Glasgow coma scale, local karma school or a sailing certificate as a silky blank drowned person's passport, allowing access to all underwater boats of the world.

But how can a living person prove they are alive? Here I am, but it's not enough for you! The only thing I want from your newspaper is the correction of the publication about my death. How many more times will you see this message? How many times have you already seen it in your Instagram inbox, your Facebook messenger, your daughter's TikTok, your mom's WhatsApp? Until you publish the correction, your Peloton will scream for my comeback, your virtual yoga teacher, clenching her jaw, compressed by a sharp spasm, will stifle my name twice, and a new episode of you-know-what on Netflix won't start until you start my heart, stopped with your stupid unverified news.

You had plenty of time to write the correction. As soon as the news came out, written by you, about a woman with a blue scarf – the one with a blue scarf – the blue scarf from that photo – that particular woman rescued from the ruins of the school destroyed by bombs – that she actually didn’t survive – the woman with the scarf didn’t survive – I wrote you a message: that was me. I am alive, so I need a correction.

What would I do with your questions? Am I really myself? How could I prove I am the bleeding woman on the photo? Well, every creature that has consciousness recognizes itself even being depicted as dying, disintegrating into gray pixels and digital blood. It’s my blood, it’s my gray face, it’s my doctor who talked to you, it’s my photographer whom you quoted, it’s my life – and I still have it, look, I am holding it. Apparently, that's why my hands are clenched into fists in the photo. When I unclench them to write you about this, my life floats around me like a quiet light cloud of fog – there is a radiance, but there is no light, but there is a radiance, so I am sitting in the dark and can’t make a video call, but by life is here, it’s mine.

I can’t make a video call, obviously, because the connection is poor here. I have no passport either, I left my bag at school, which, as you remember, burned down, blown to pieces. How a person with burnt documents can prove their existence? Especially now, when a dead person can easily text anyone? Especially if you haven’t noticed the awkwardness of the previous phrase and keep reading this as if we are just dealing with some slippery social media scandal here.

You asked me to specify my location. Well, I can set rules here too – dear, you have taken my life, juggling it, as if it fell apart into a hundred shining golden balls as soon as you touched it. I can’t tell you where I am until I see a correction in your newspaper.

It’s very simple. A correction is a normal, familiar procedure. Journalists do make errors, it’s fine. Just provide a correction. Dear readers, an unfortunate error crept its way into our news article. The woman on that graphic image we actually blurred, is not dead (so we can unblur it probably).

I need an official cancelation of my death. You must cancel it in exactly the same way you’ve announced it earlier, weaving it out of false testimonies and releasing it into the world like a virus. I won't agree to anything else but an official correction. If I don’t see it, I will sue you. You know what court I am talking about.

But since I decided to talk to you in your language – and I looked into your vocabulary, like into a cold well, and I ran like a happy little fireball through your social networks, and I drank ice compote from your sleepy dog’s bowl, and I turned into a tiny miserable flower, forgotten between the pages of your book – I admit the impossibility of reaching you through the front door, so I have to beat my head against a dark door in the back.

You probably do not have a media genre for a no-death announcement. A correction notice on death is always a resurrection trick, and that’s what is binding your tongue. I noticed this some time ago, when one of our famous blogging journalists was killed in an assassination attempt – you know who I am talking about, but since you don’t believe I am me, I decided to forget everyone’s name here – tons of publications quickly broke out, emerged, appeared – do you have appropriate vulgar verbs for thoughtless reproduction of obituaries? Well, there were many of those. But the next day it turned out the journalist did not die, but did not survive either – let's say he walked past death alive. What is the word for this? Resurrection? In media context, for sure, that was a resurrection. But how do you write about resurrection?

That summer evening it happened I’ve been drinking with friends at my place – I won’t mention their names, otherwise you’ll immediately interrogate them, trying to figure out if my leg on that photo was removed by a missile, or by a photographer’s twitching hand – and we discussed a professional journalistic failure in canceling death. How do you write about the fact the deceased is now alive? After all, this thing perhaps will be necessary in the future, when people begin to resurrect en masse. So we need a new media genre that is directed to the future – an antithesis of an obituary. It has to correspond it formally, while contradicting it emotionally. The same way there are rules for writing an obituary, there should be rules for writing a reverse piece – a heartfelt note on reversibility of non-existence.

It is probably the absence of an anti-obituary genre that gives rise to media frustration – this is what I see in you. An obituary has a well-established ethics, but an opposite genre not only does not have this – it does not exist! But I do exist. So the genre does as well. I came up with a beautiful name for it – Anastasis. Yes, it is "resurrection" in Greek.

The rules of writing an Anastasis are simple: it must be laudatory, jubilant, including all the elements of the corresponding obituary (for example, if the obituary says about something we’ve lost, in an Anastasis you have to mention what we’ve gained back! If the era has gone forever – hooray, the era has returned). The tone of Anastasis is quiet, calm, restrainedly enthusiastic, relaxed but victorious, full of reverence, but at the same sparkling with irrefutable confidence that what happened is a long-awaited norm, not an absurd cancellation of an accident.

The most important thing while writing an Anastasis is not to present what happened as an anomaly. Celebrate resurrection as a rule of life, while refraining to cancel a preceding obituary, since it’s a transitional evidence of a human existence from life to death, and from death to something more true and understandable than both life and death.

So far, all the liberal media have unanimously failed an Anastasis. Anyway, I do believe that in the future this genre will sprout and break through the asphalt of your helplessness in the face of the reversibility of the irreversible. Anastasis will become my second name, while you still fear to mention the word “alive” by my first one, my inexhaustible one.

As you can see, I gave you all the tools for manifesting my life and bringing it to light – bringing us all to light. Yes, it was an error, you made a mistake, but just admit it – or at least publish this letter instead of a correction, if a correction is too embarrassing for you.

I believe you can publish it somewhere. You definitely need to send it somewhere. You have to let us speak with it. Please make sure that this genre name remains – so that at least something remains of me. Just name it after me. It’s how those scientists name some imperishable diamond dust butterflies after their unfulfilled lovers, who may suddenly feel a touch of heavenly heaviness landing on the corner of their beach book – as if the tonguelessness of an abyss has wafted the greedy heat of a hail. And while we still do not know how to speak, we will keep writing to you.

SPECTERS OF COMMUNISM: CONTEMPORARY RUSSIAN ART James Gallery, CUNY Graduate Center, NY, USA, 2015 curator Boris Groys

Boris Groys

Excerpt from Specters of Communism: Contemporary Russian Art, The James Gallery and e-flux, New York

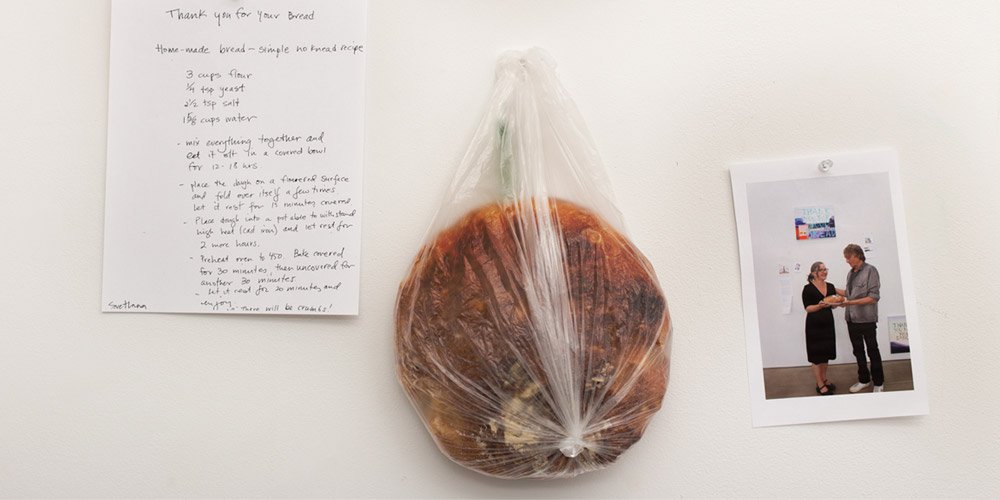

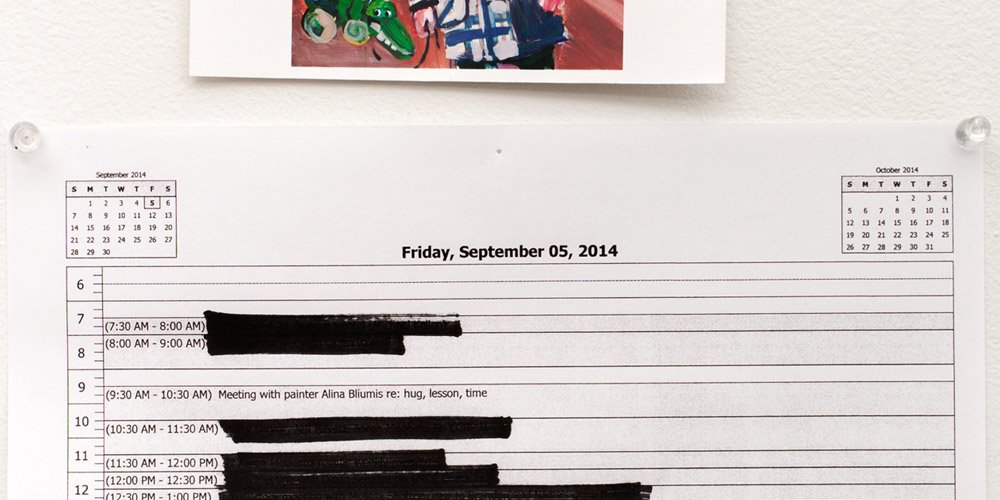

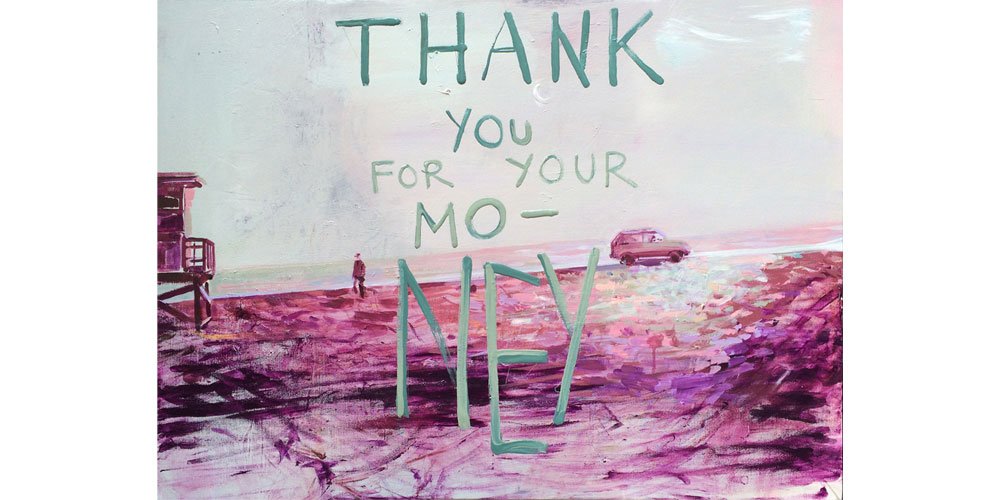

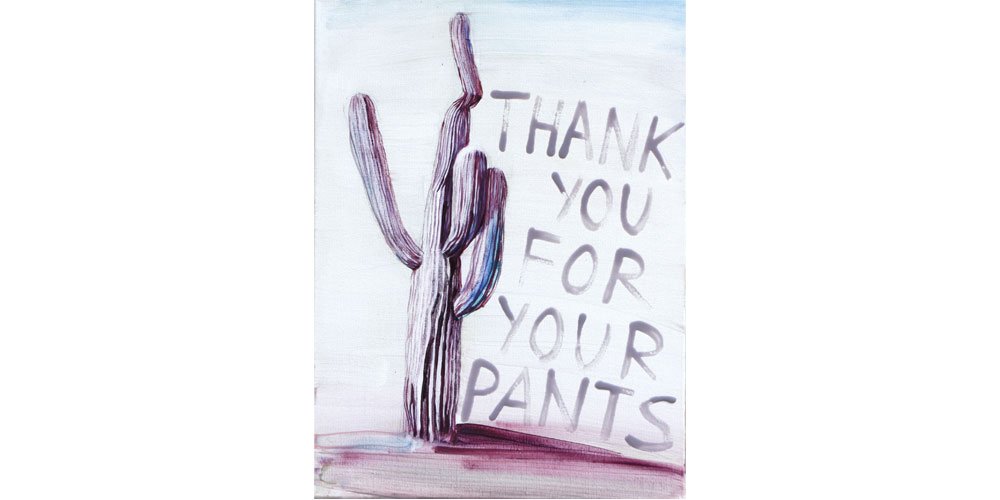

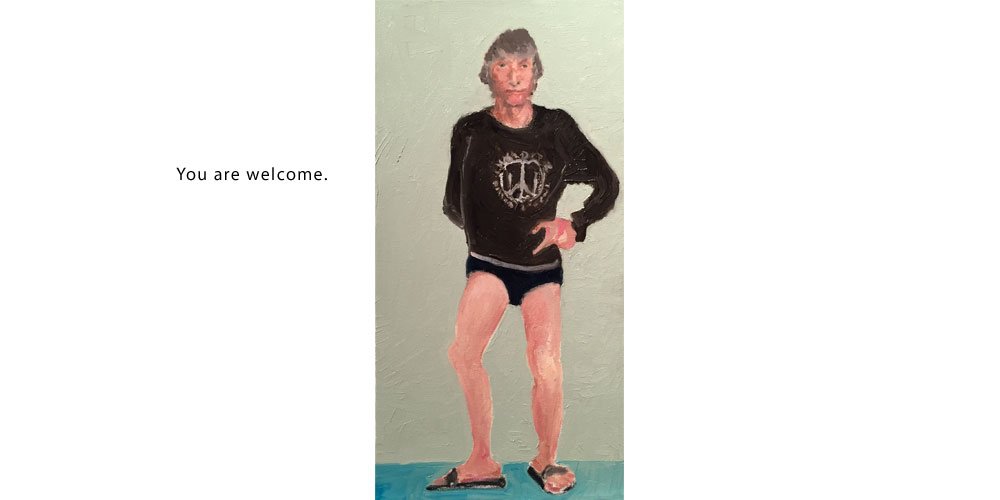

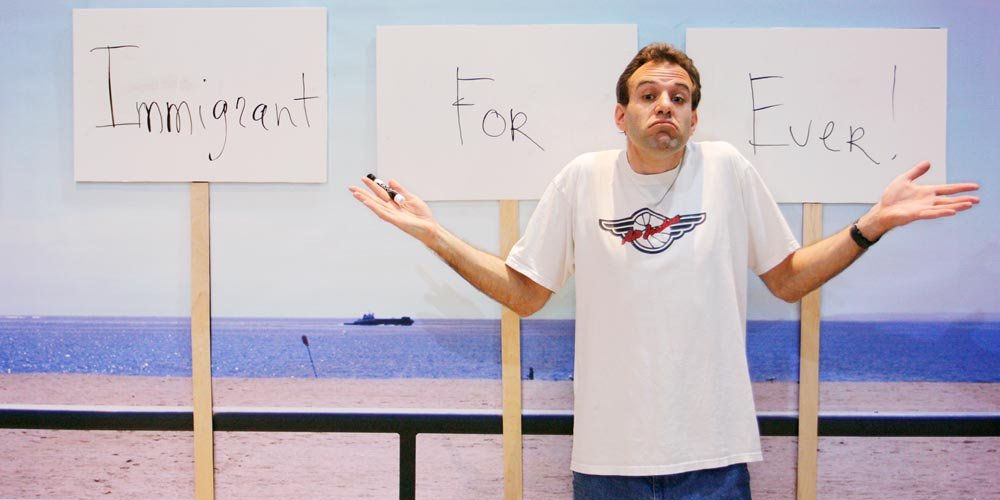

"Jeff and Alina Bliumis, a pair of New York-based, Russian-speaking artists born in Moldova and Belarus, respectively, also open themselves up to the potentialities of new landscapes in the work that produced an installation of thirty-nine 24 x 24 inch photographs at The James Gallery. For their long-term project A Painting for a Family Dinner (2008-2013), the Bliumis' traveled the world from The Bronx to China stopping in Italy and Israel, looking for hosts who would exchange a home-cooked meal for a small sweetly but primitively rendered painting. Their project, which is the only one in the exhibition that does not directly engage with Russia, is documented through photographs where they stand with their temporarily adoptive families and in a set of limited-edition books that trace the project's steps within each country. Reviving the barter system in the twenty-first century when our transactions have advanced to new currencies, like Bitcoins and devices like Apple Pay, the Bliumis' humble proposition is inspiring, even though its success is not guaranteed in the capitalist system. A Painting for a Family Dinner allows us to see a positive side of communism because it puts into practice the notion of equal and shared property circulating within an international codependent community".

FOREIGN BODIES, Set Gallery, Brooklyn, New York, USA; curator Yevgeniya Baras

In collaboration with Jeff Bliumis

HULA HOOP

2010, Bronze, 35 inches in diameter, Edition of 4