BETWEEN TEXTS AND TEXTILES Bienvenu Steinberg & Partner 35 Walker St. NYC July 21 - August 31, 2022

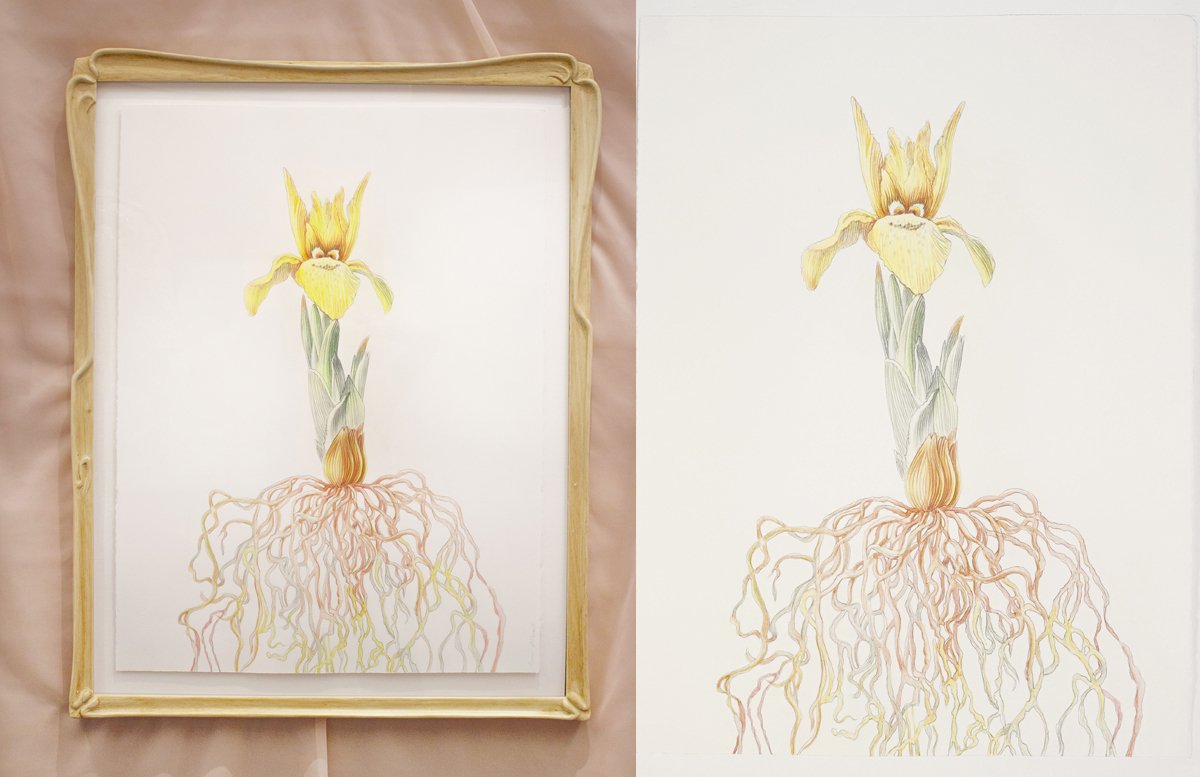

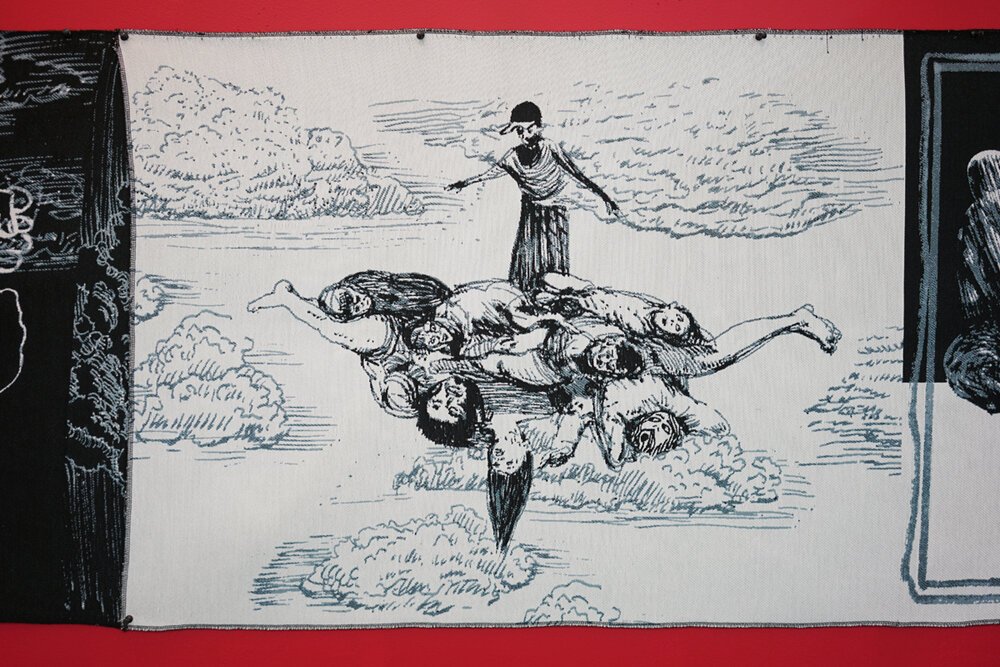

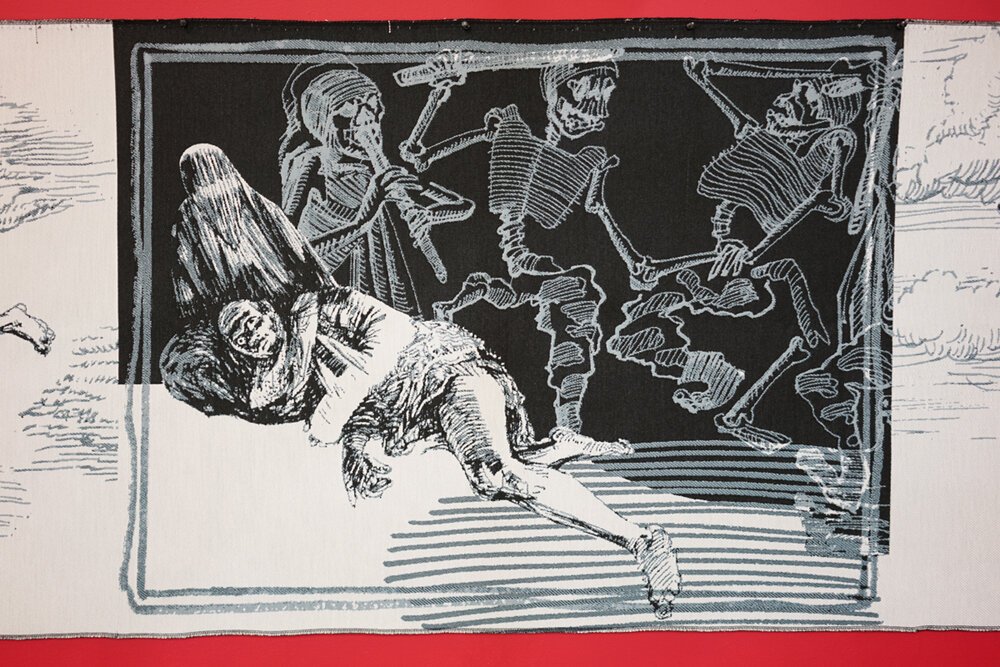

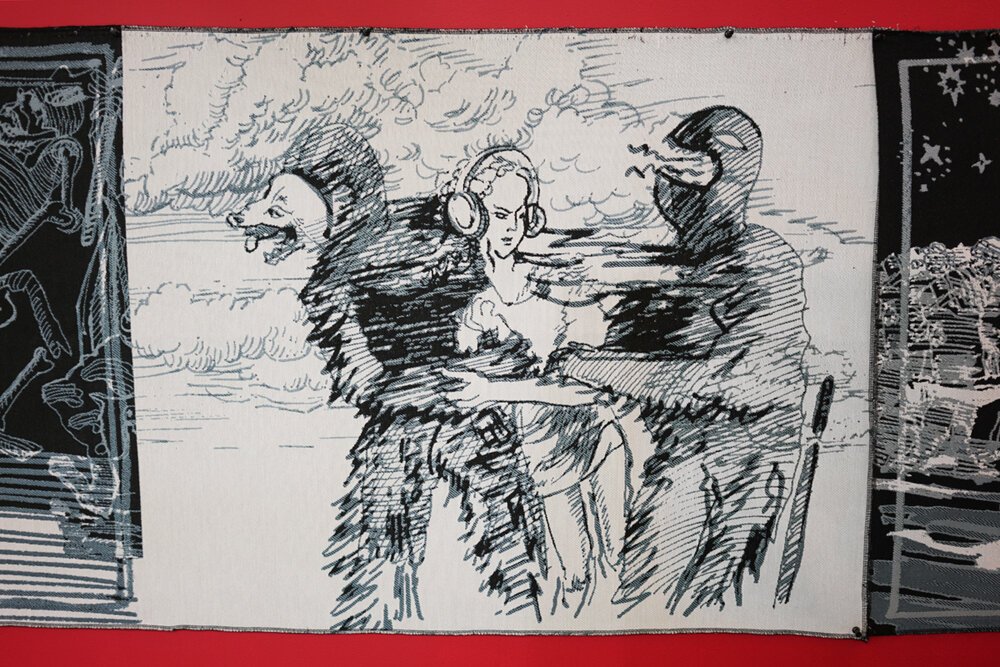

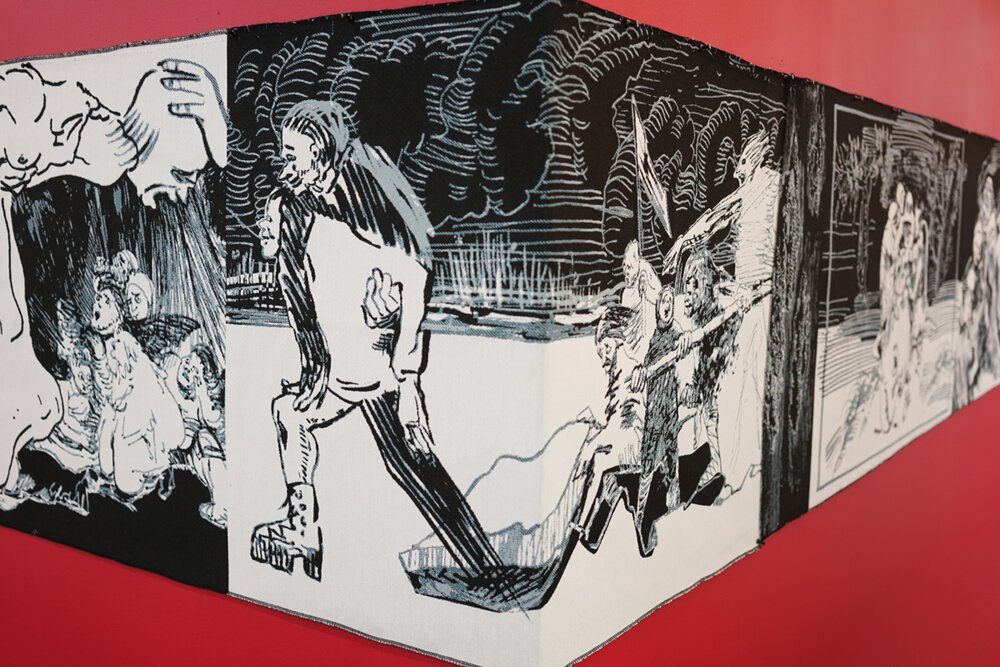

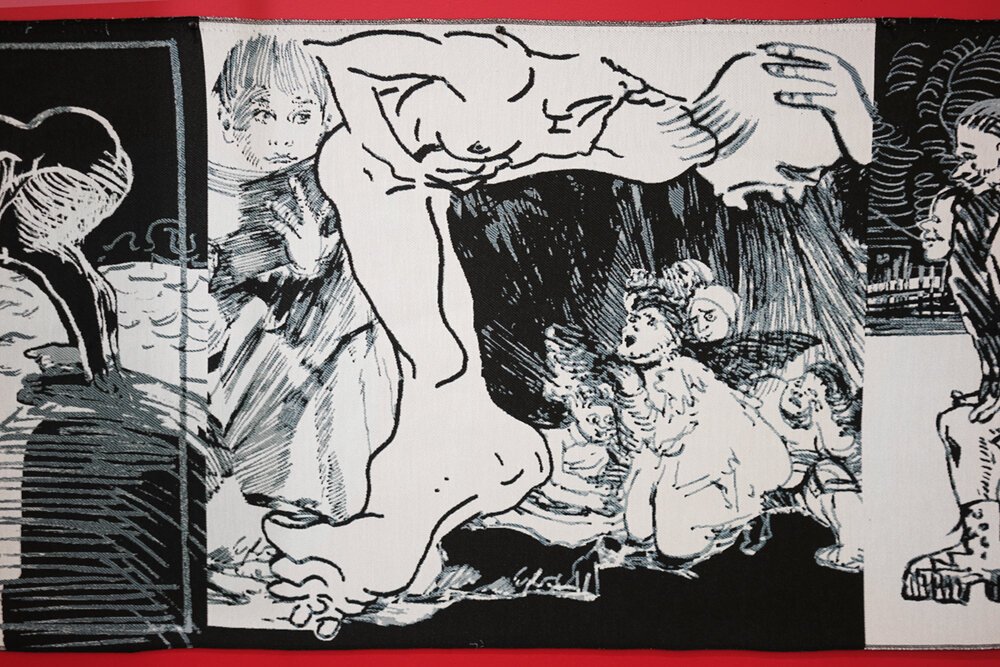

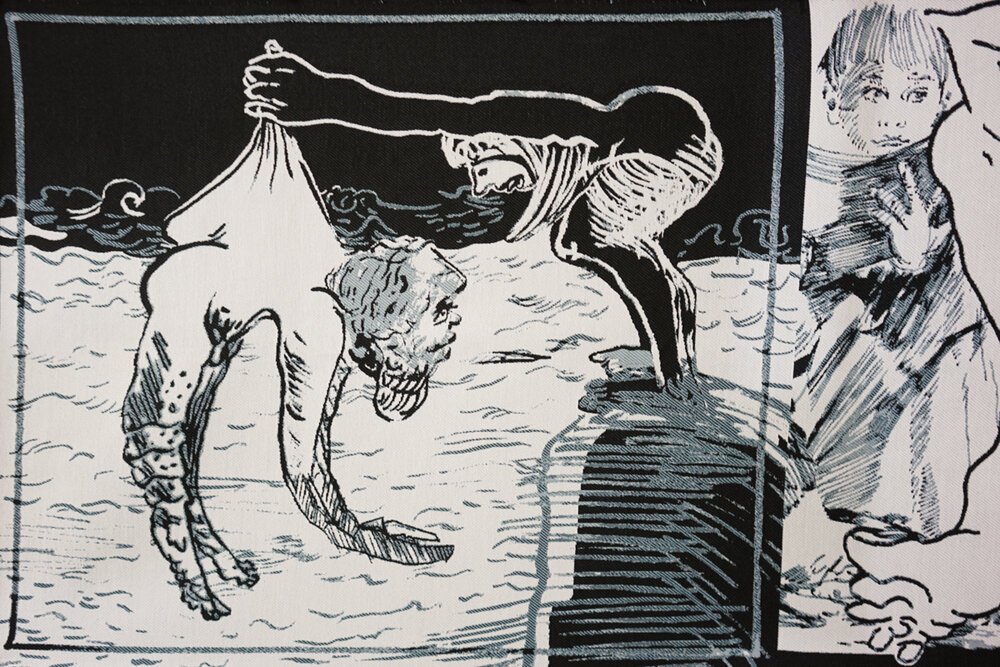

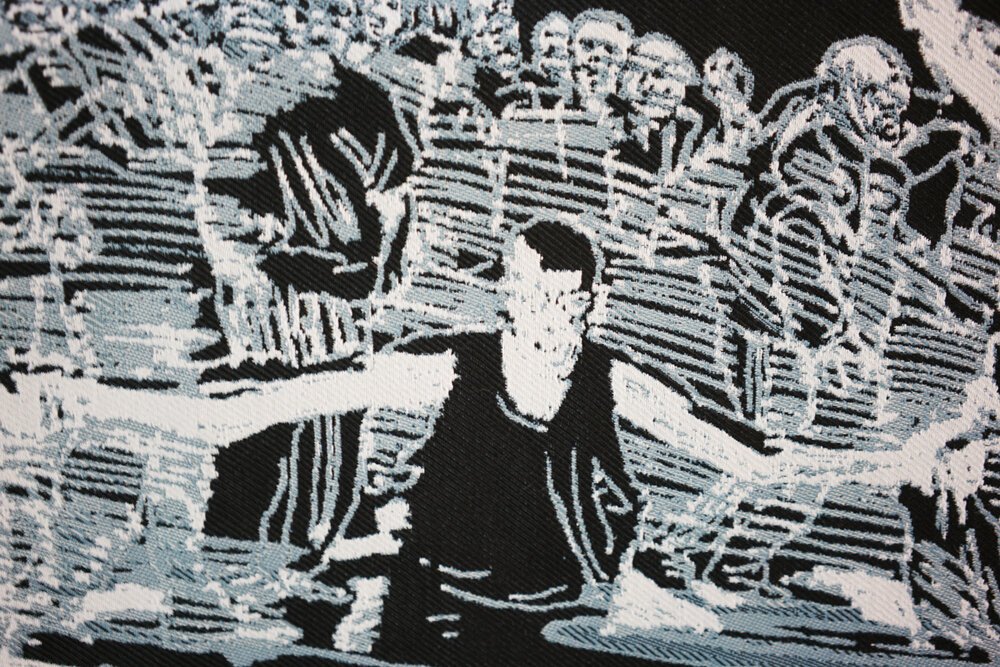

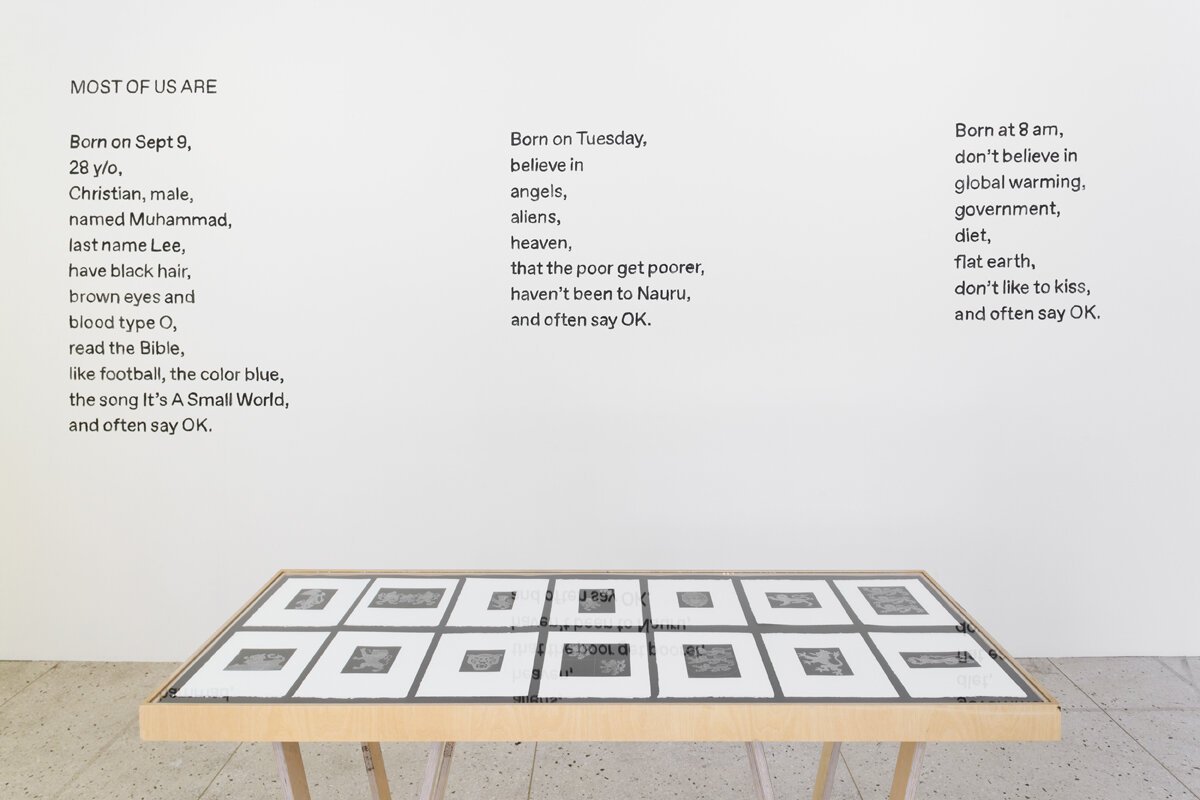

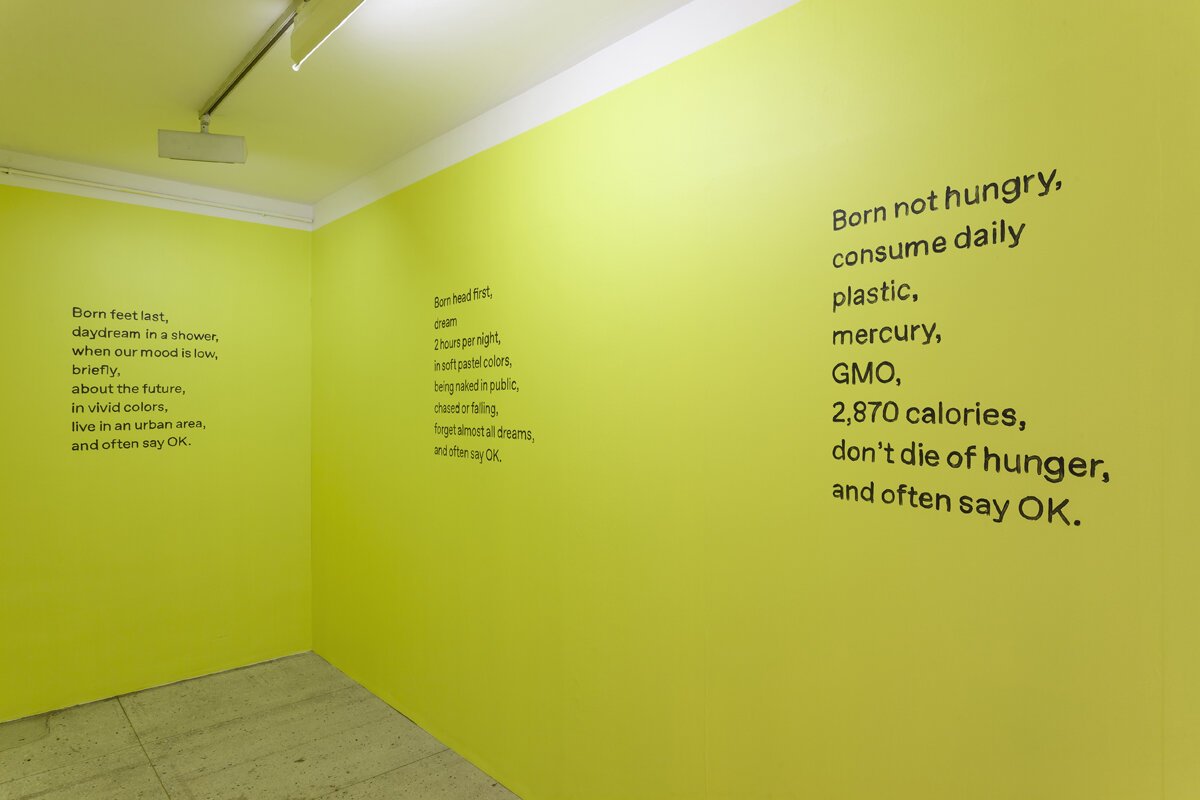

Bienvenu Steinberg & J is pleased to present Between Texts and Textiles, an exhibition including eight international artists. The works featured stretch the fabric of reality, from text to textile, from pattern to language. What is presented is a gradual approach to painting, sculpting, weaving and writing by visual fusion of what might be called the textile sign. The works break the link between vehicle and destination: textiles to be read with no intention of being informed, texts with no plot and no point.

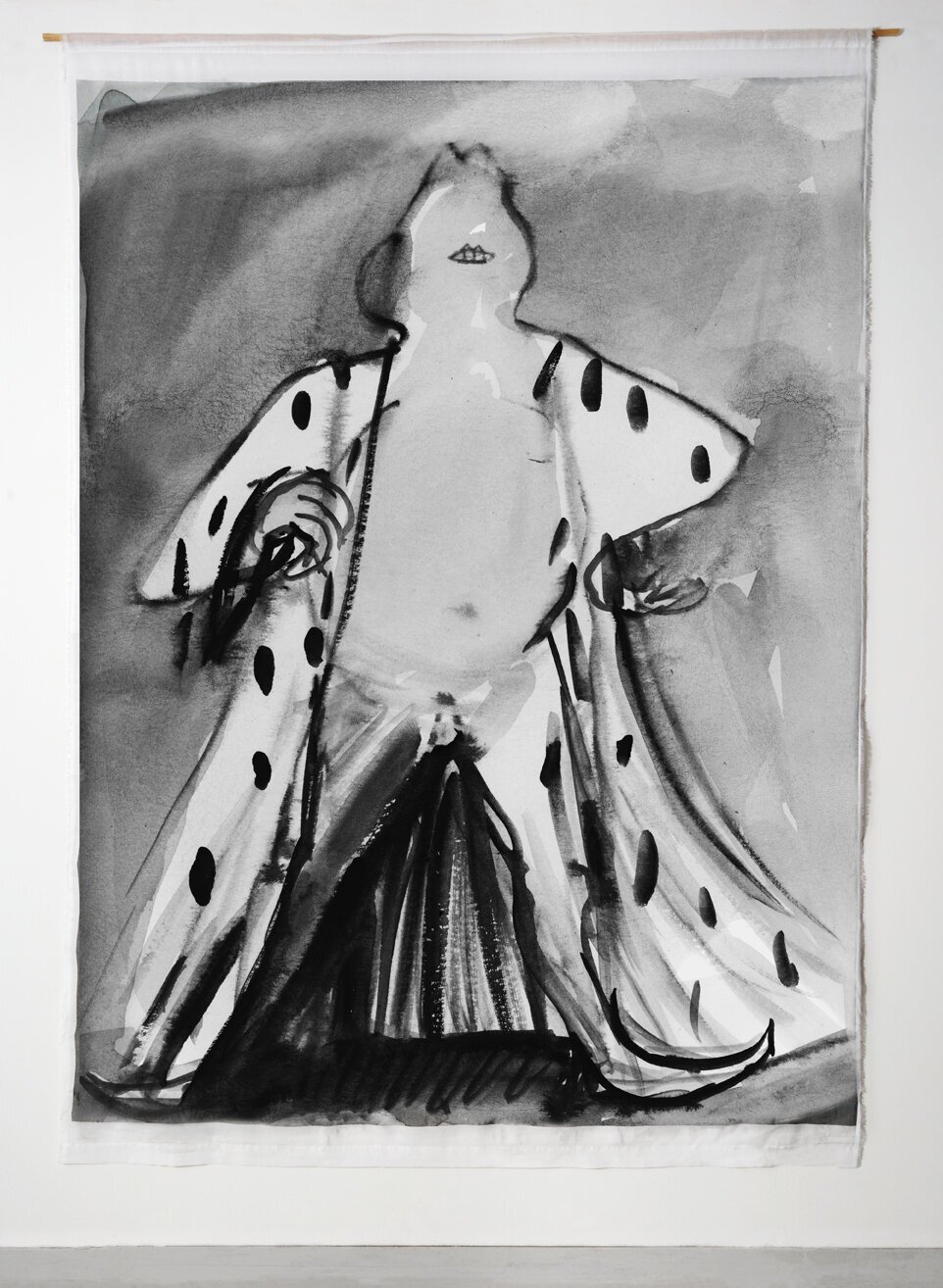

Language and text are at the tactile and metaphoric center of Ann Hamilton’s work. She uses common materials to invoke particular places, collective voices, and communities of labor. What are the places and forms for live, visceral, face-to-face experiences in a media saturated world? In Shell, an homage to Joseph Beuys, in the form of a white felt coat, as well as in a groupof collagesonbookendpaper,therelationsofcloth,touch,motionandhumangesture give way to dense materiality.

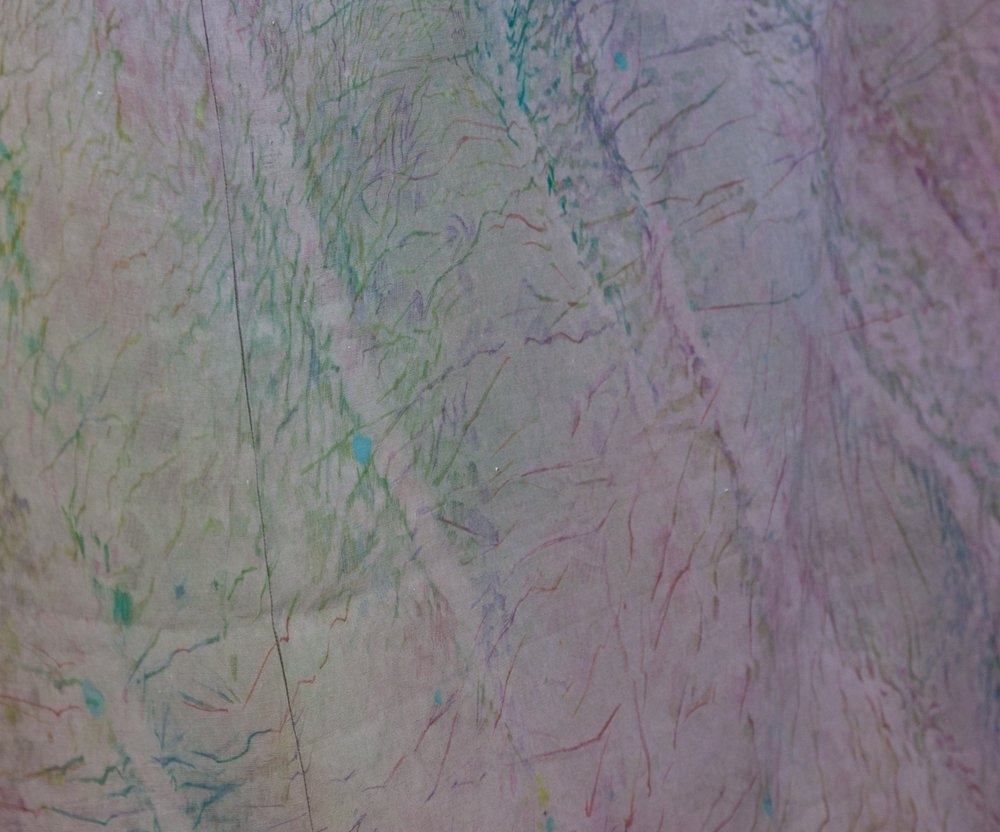

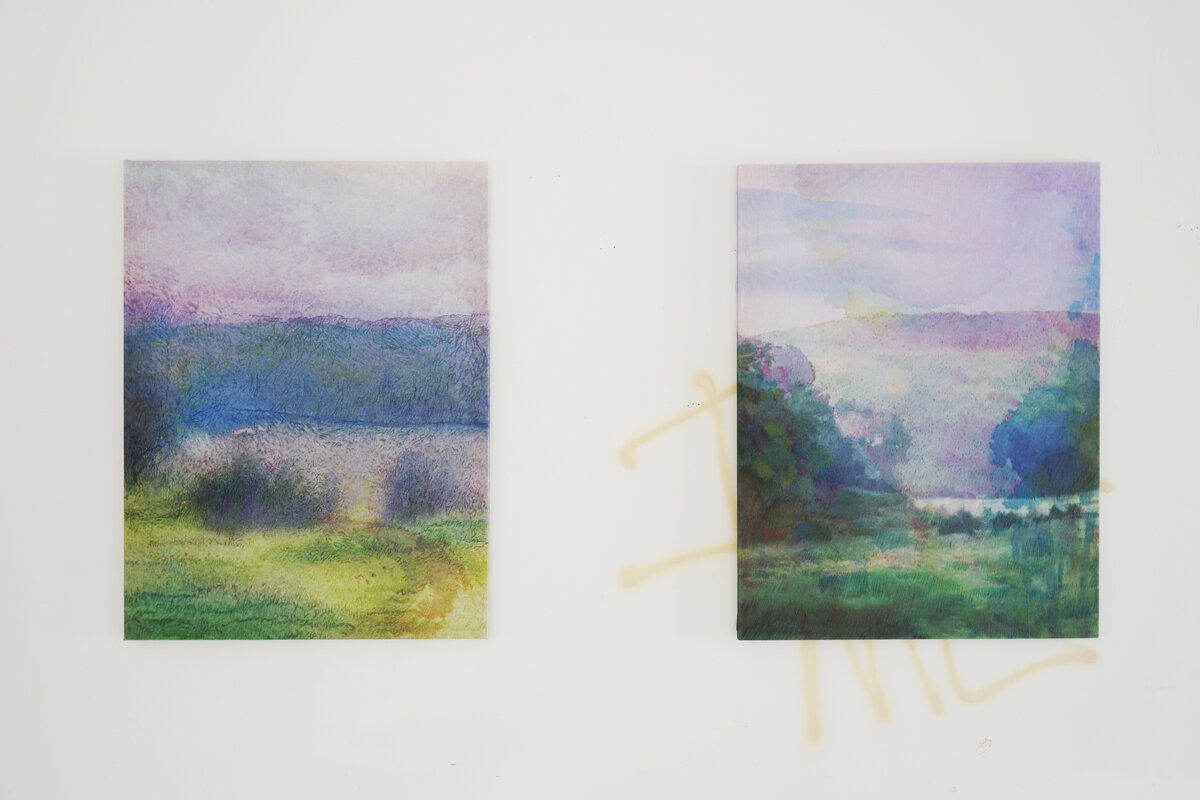

In her re-reading of twentieth Century avant-garde practices, Fernanda Fragateiro frequently repurposes already-existing and symbolically layered material, in order to fashion delicate work criss-crossed by an intricate web of inner references to the history of art and architecture. Her ongoing Overlap sculptures are made of stainless steel supports and handmade fabric-bound sketchbooks. Overlapping is an important word to talk about the essence of all these works: overlapping of elements, overlapping of materials, overlapping of histories, and time overlapping. In a new series of paintings titled Poly-Grounds, Suzanne Song creates multifaceted dimensions that blur the boundary between illusion and reality. The paintings’ shapes are direct extractions of the marginal spaces delineated from previous bodies of work. The placement of shadows disrupts the flat picture plane and transforms the two-dimensional surface into an ambiguous field: are we looking at a painting, a very finely woven fabric or a polished surface?

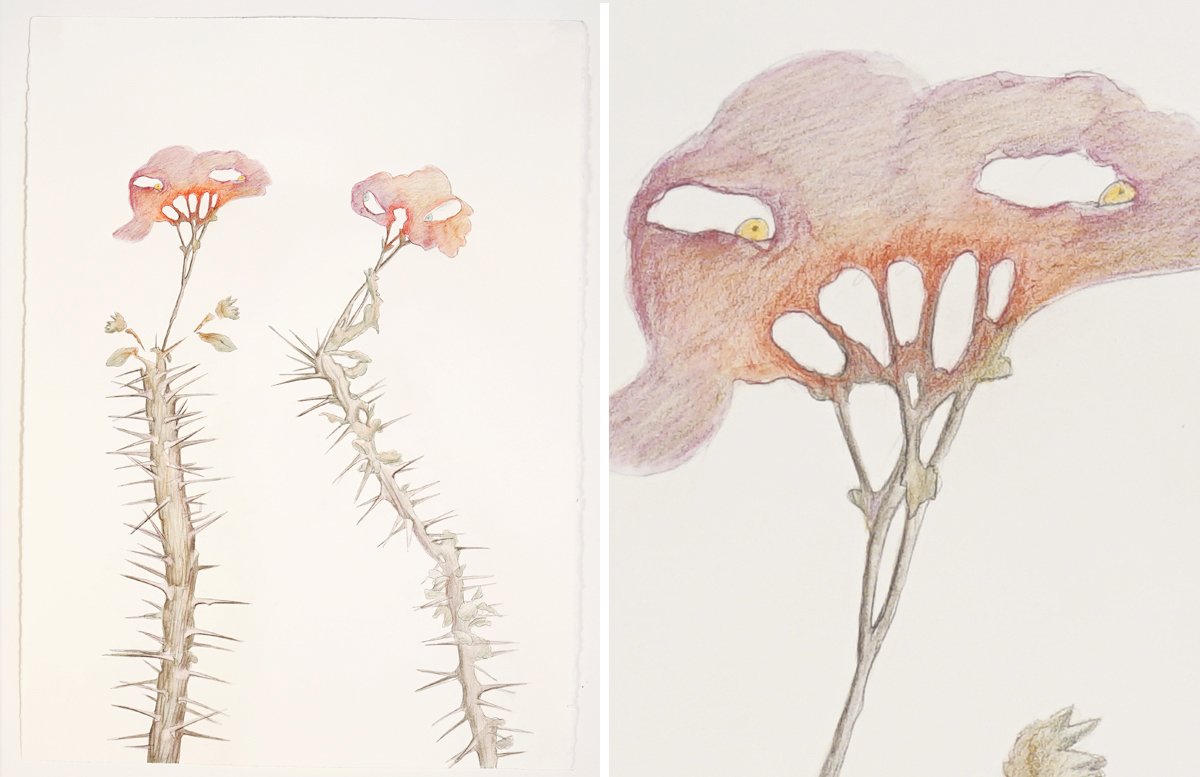

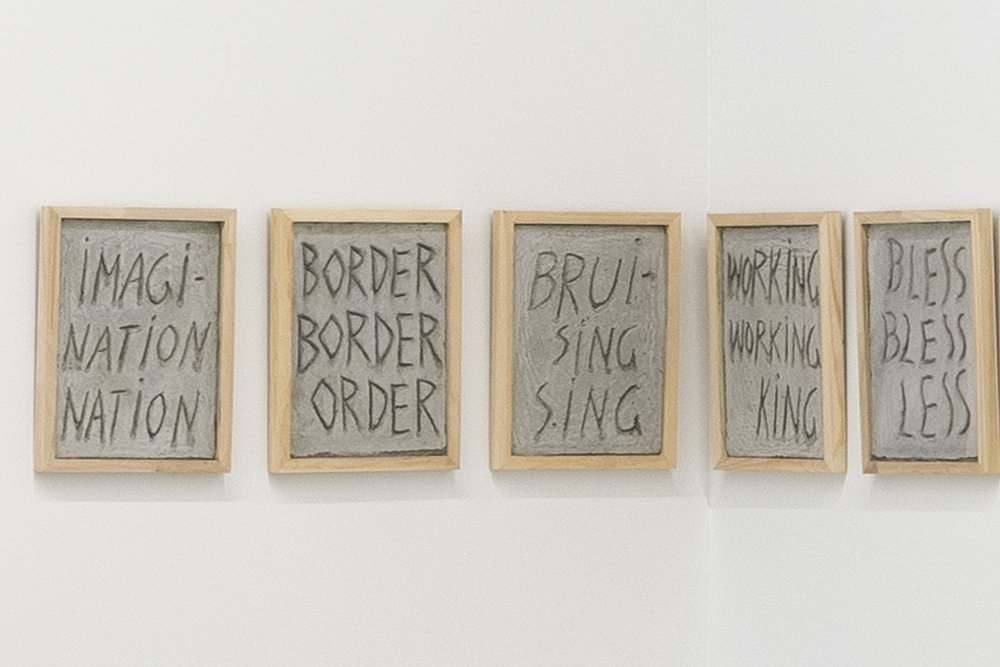

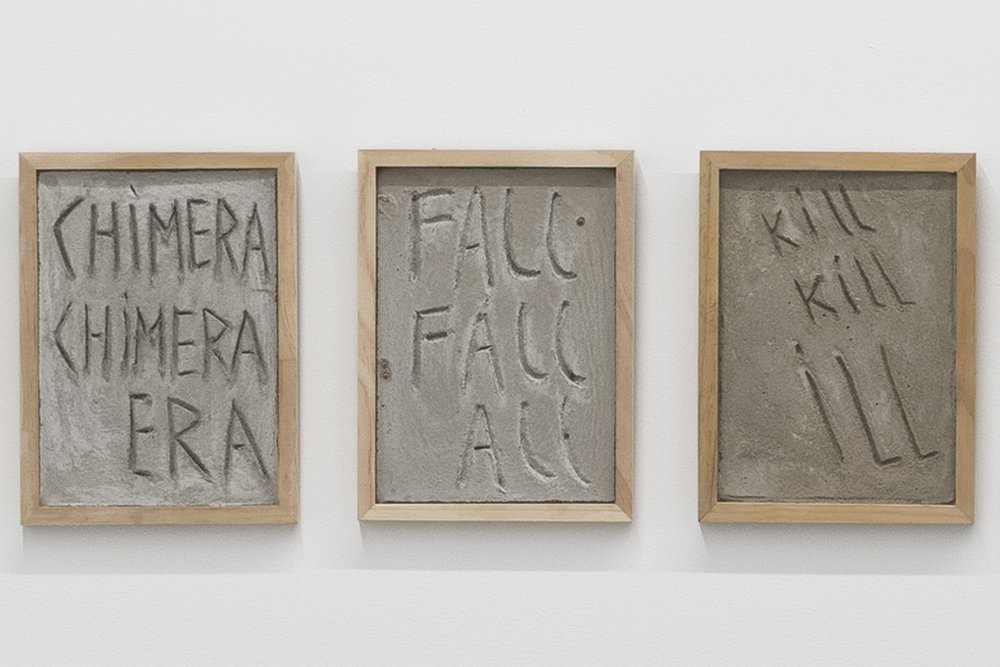

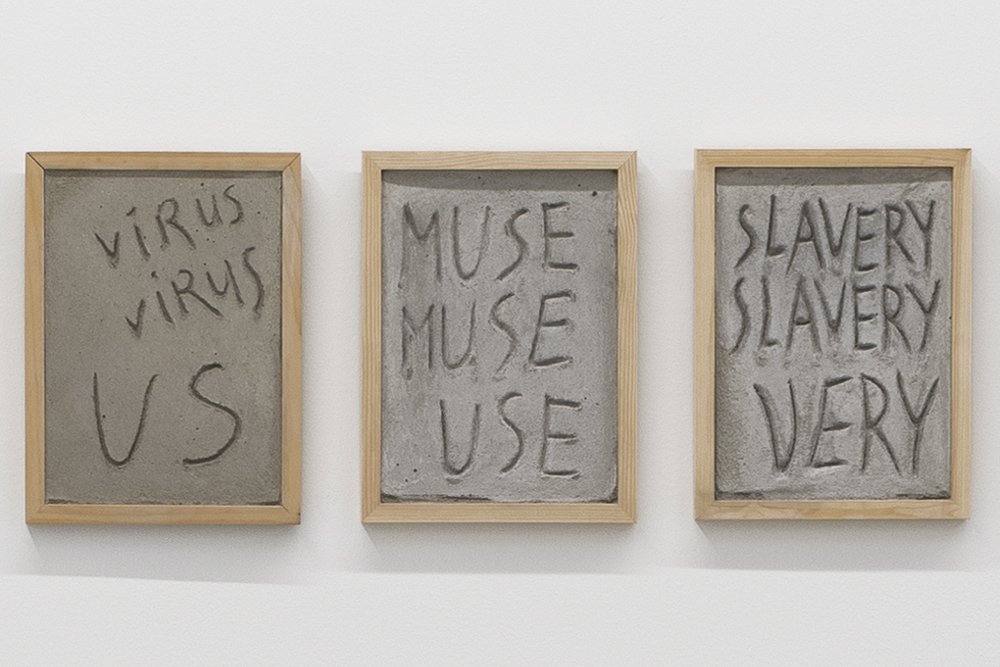

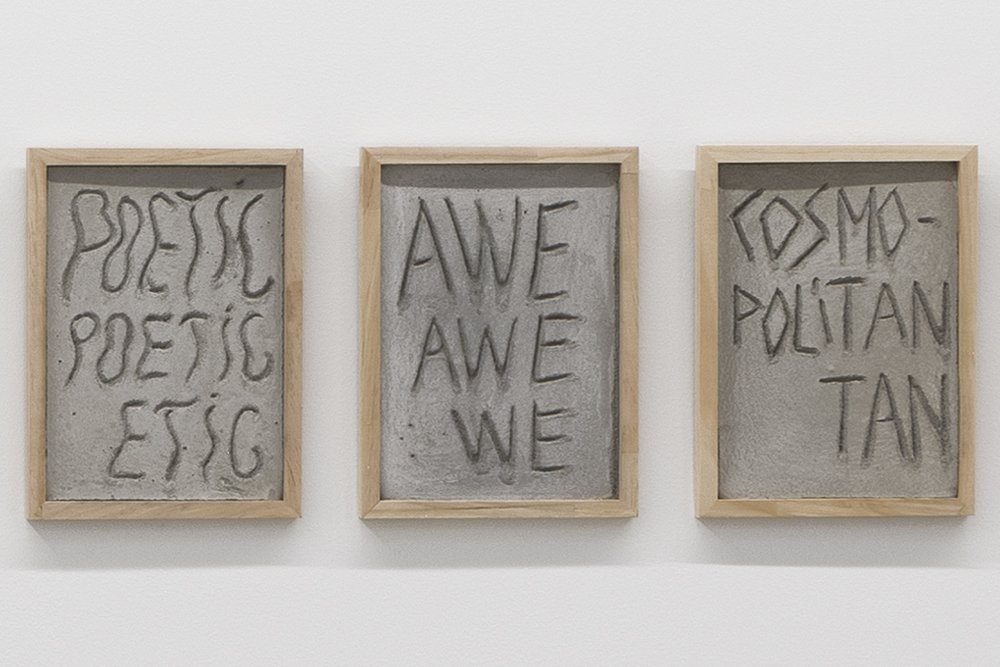

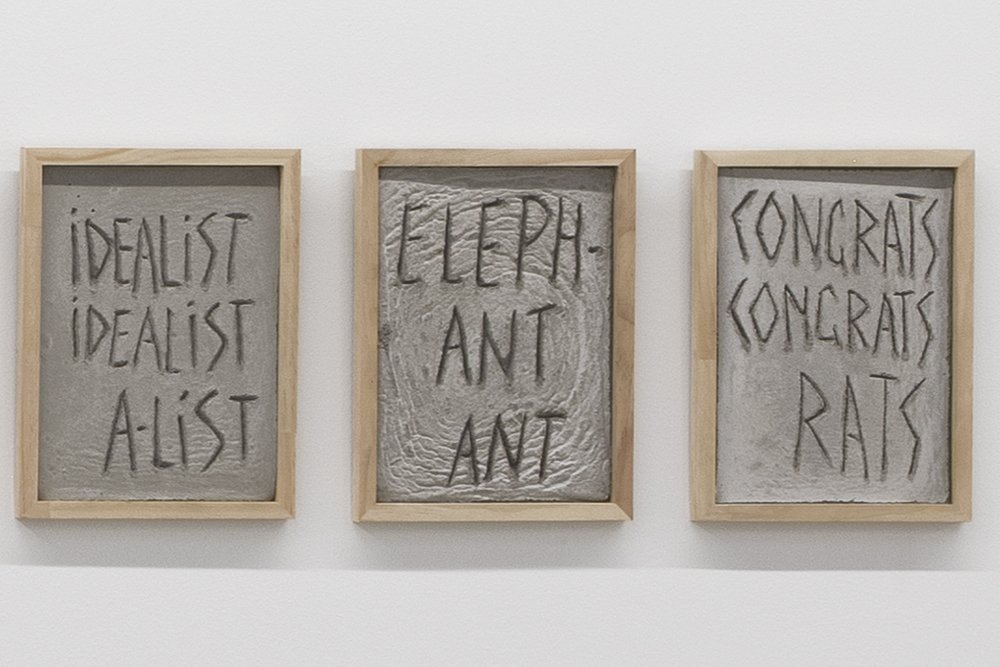

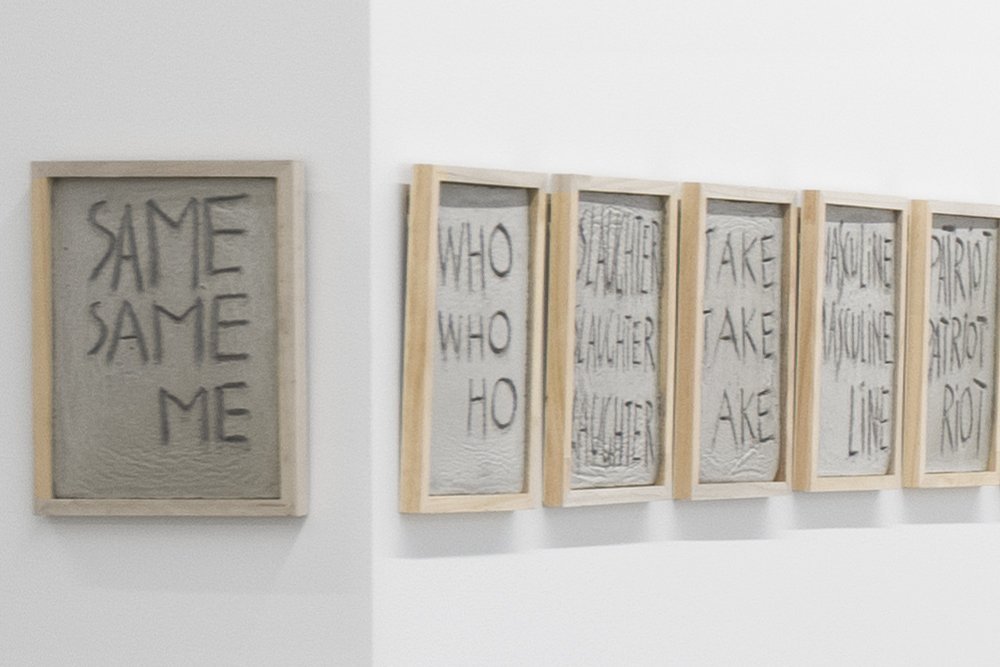

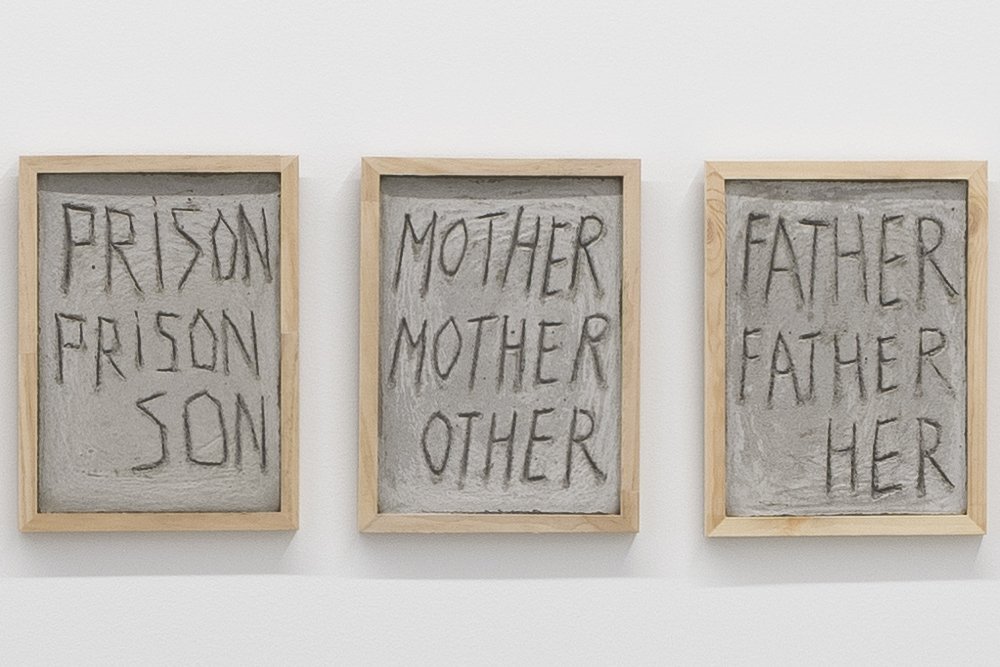

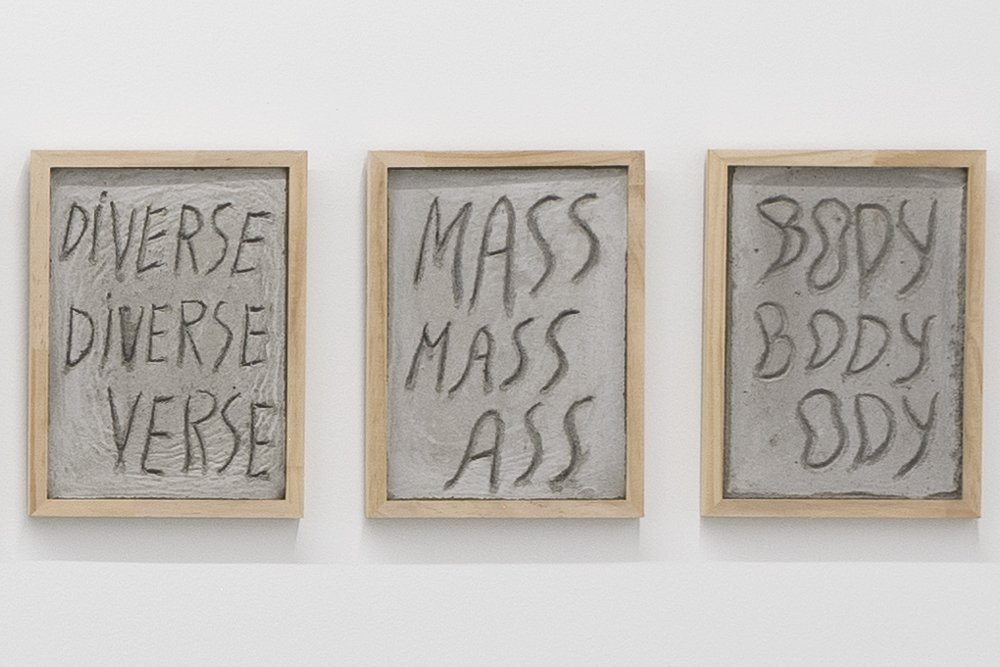

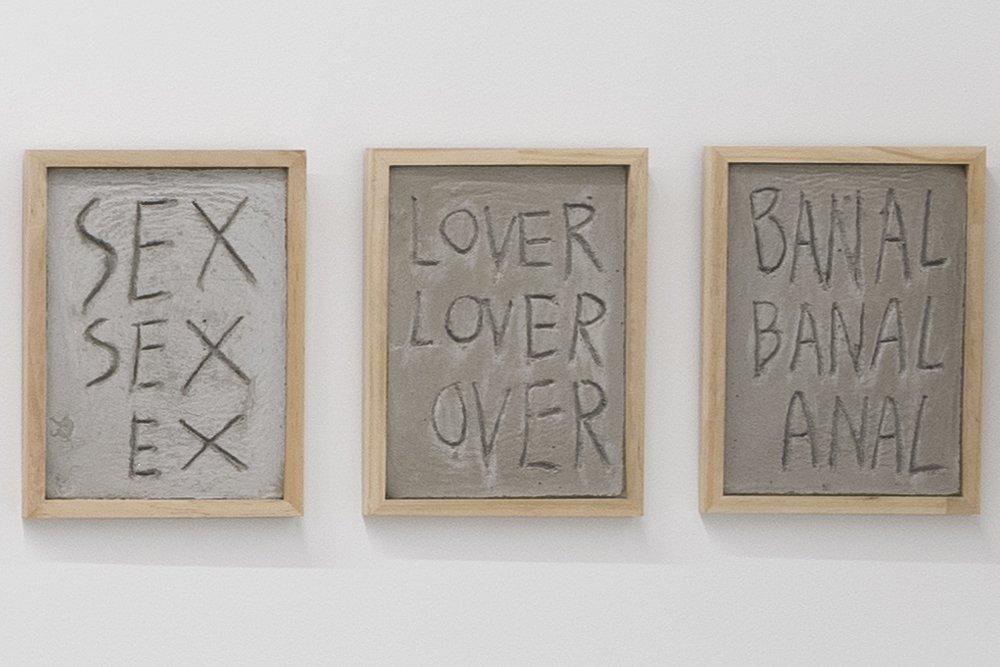

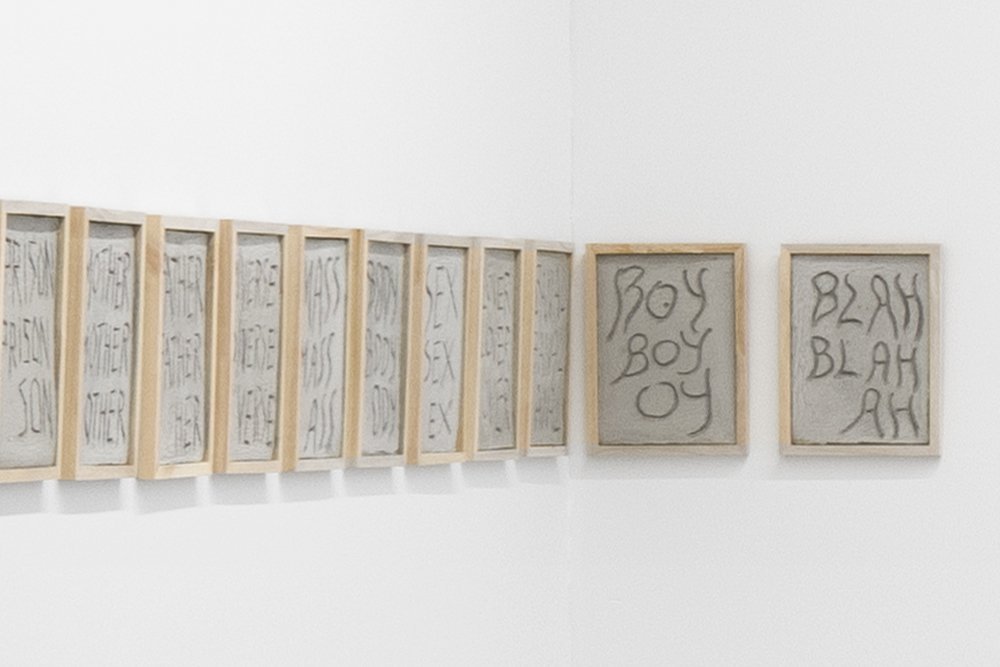

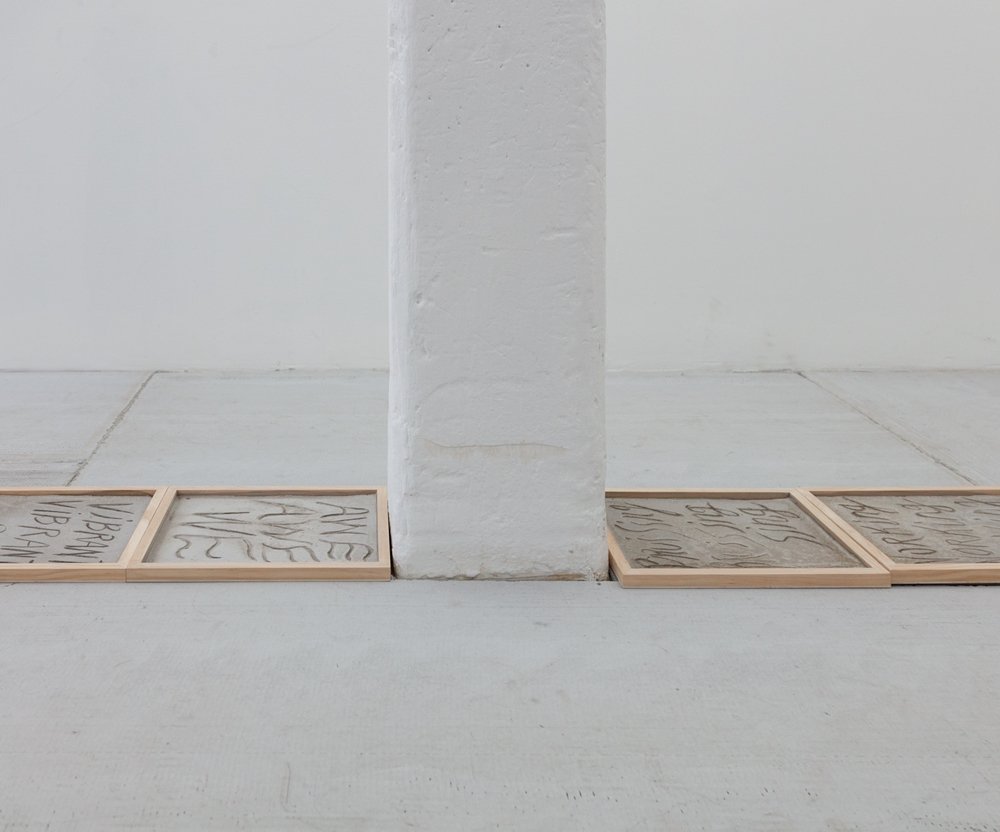

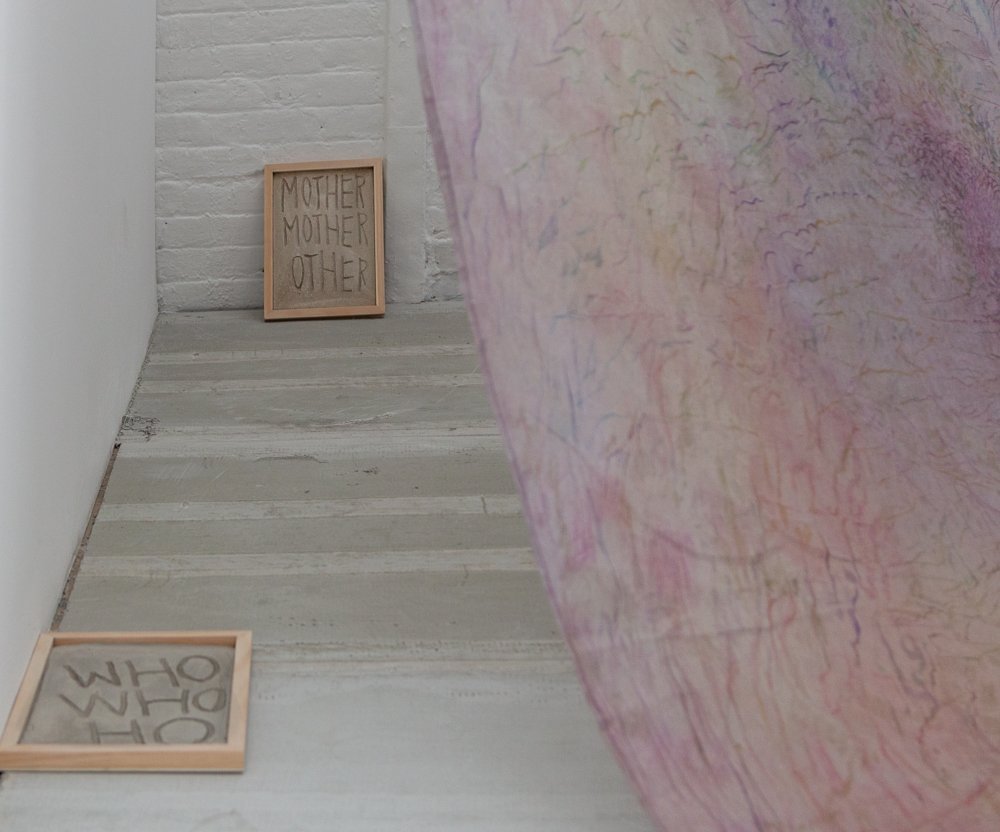

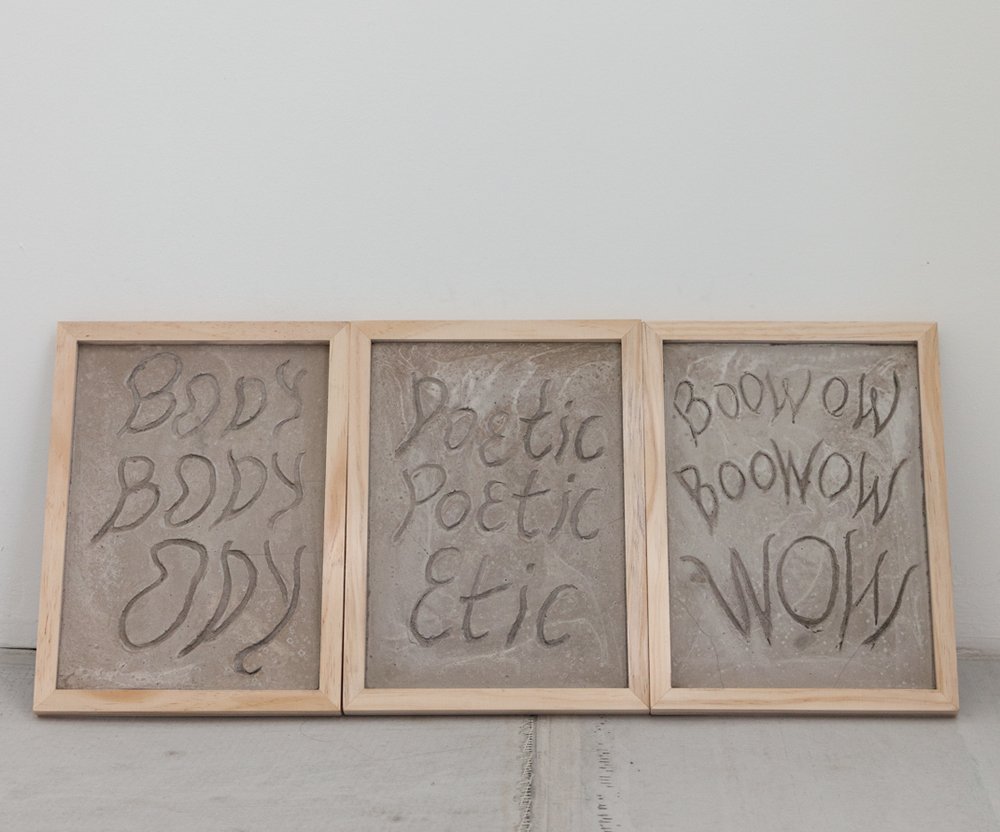

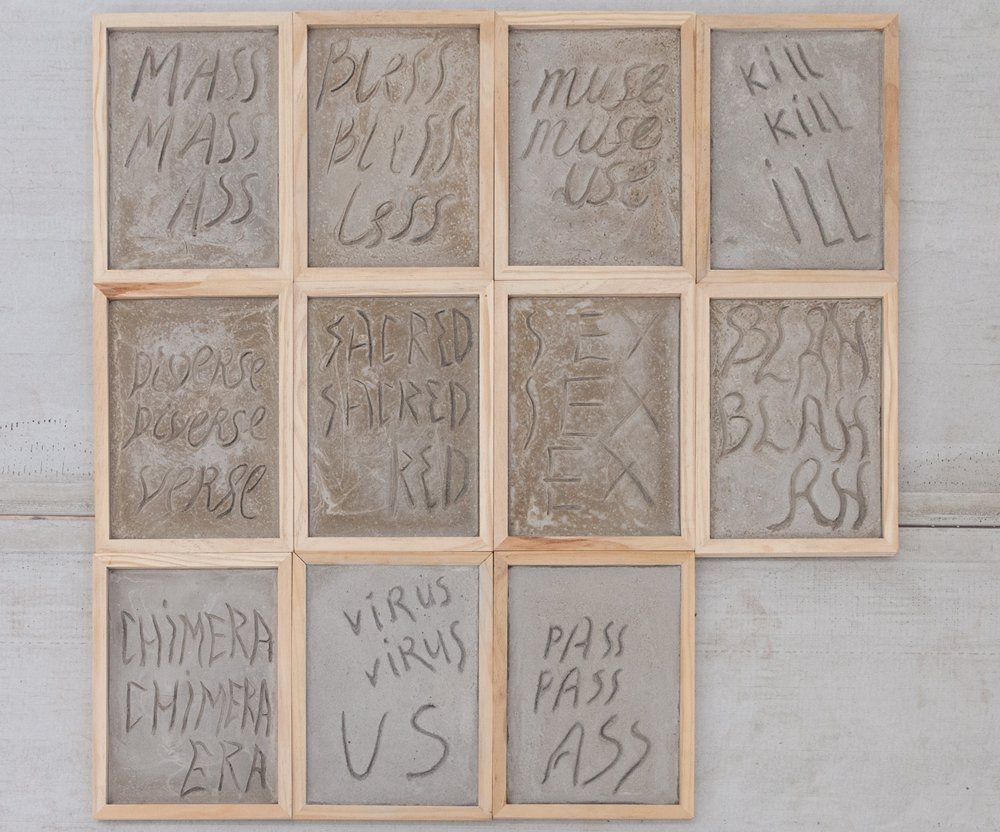

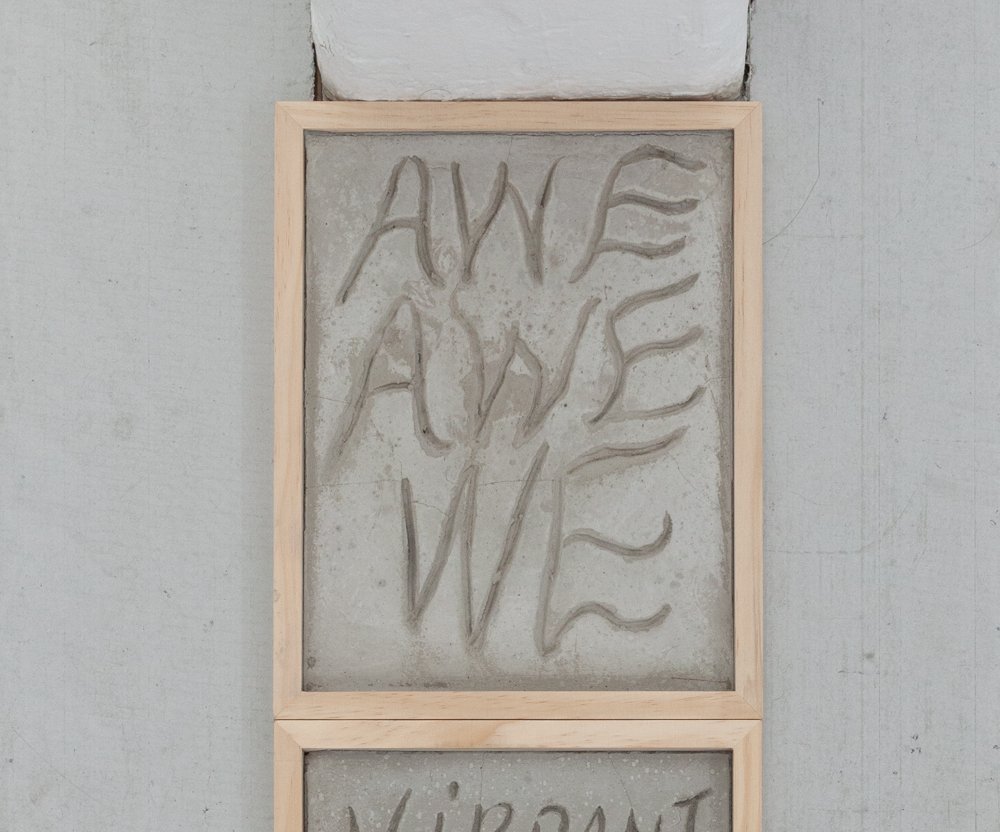

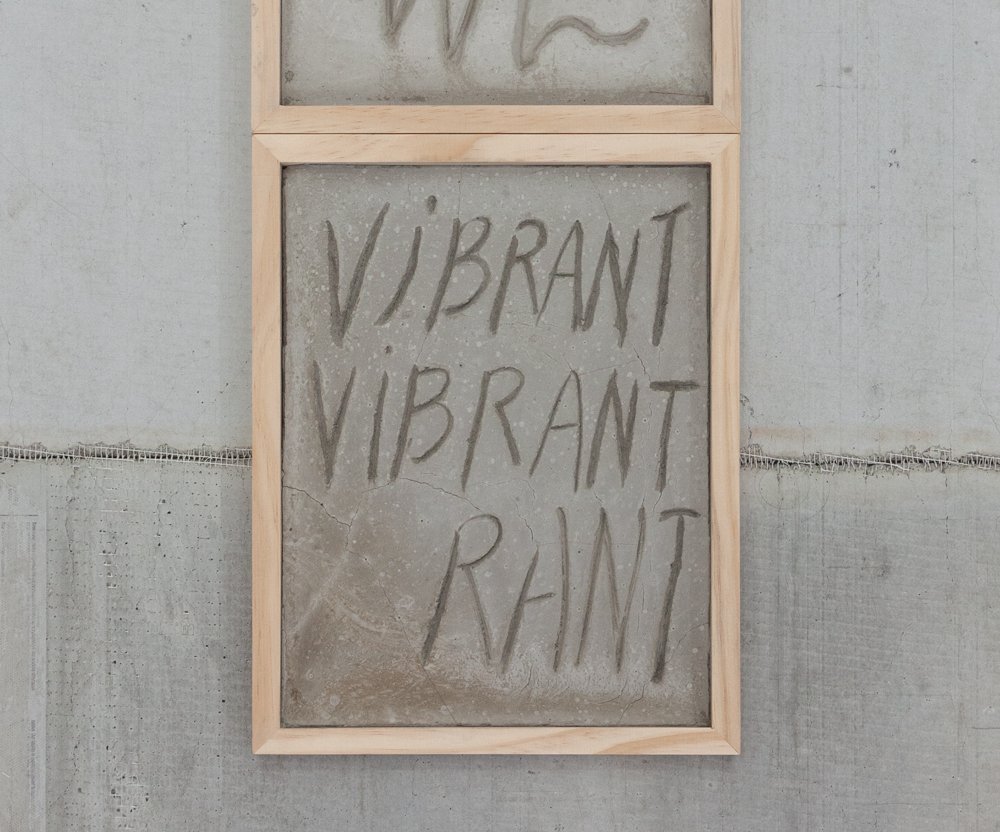

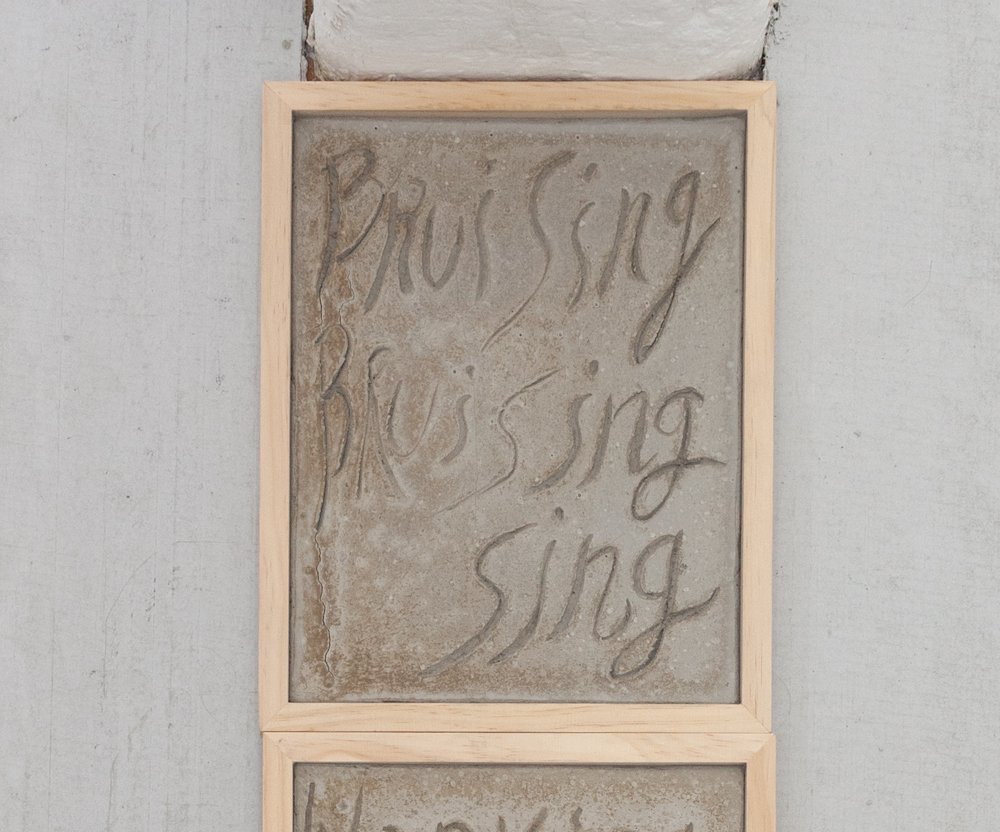

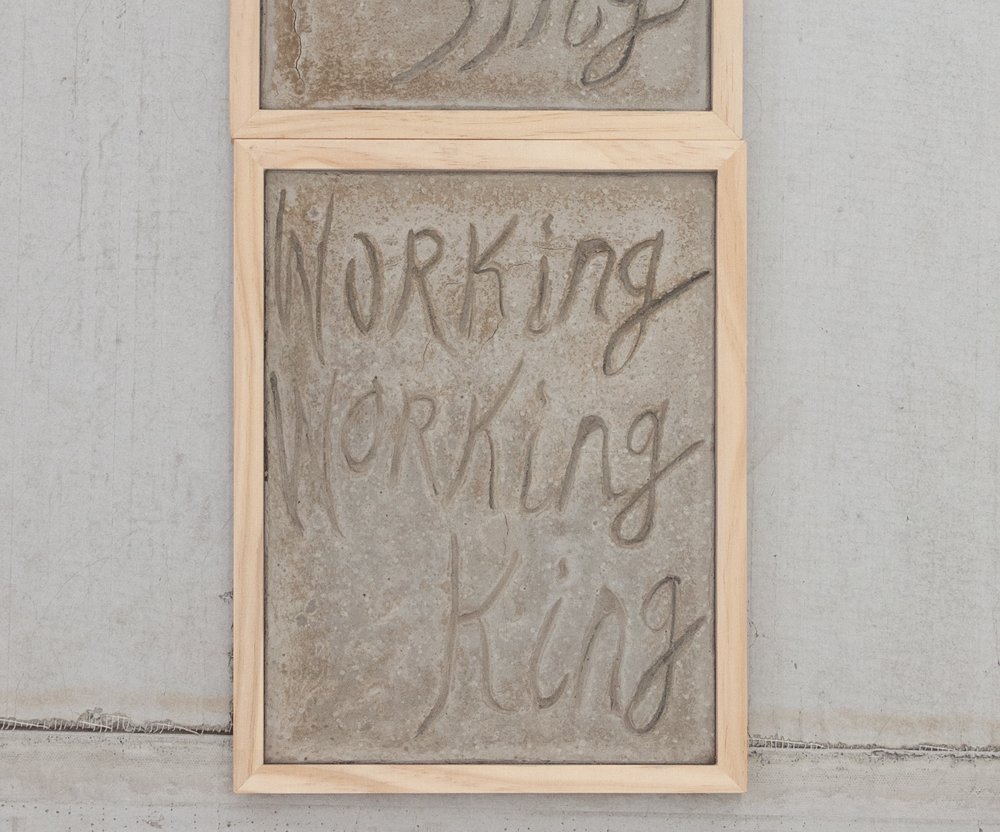

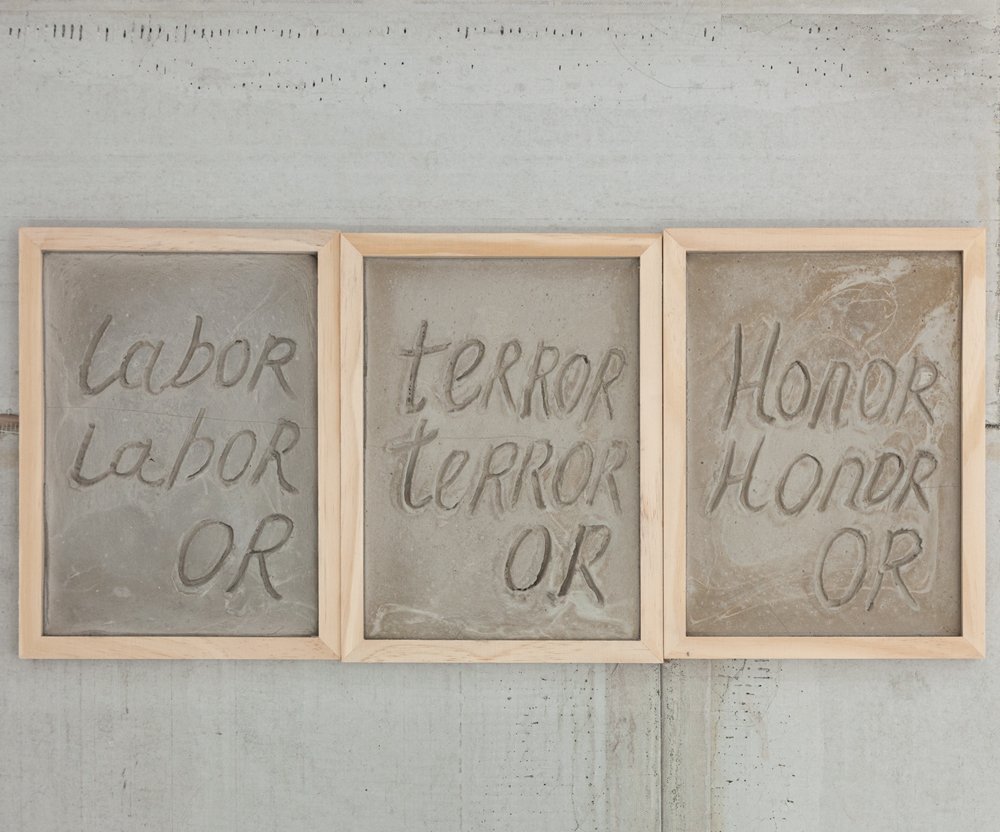

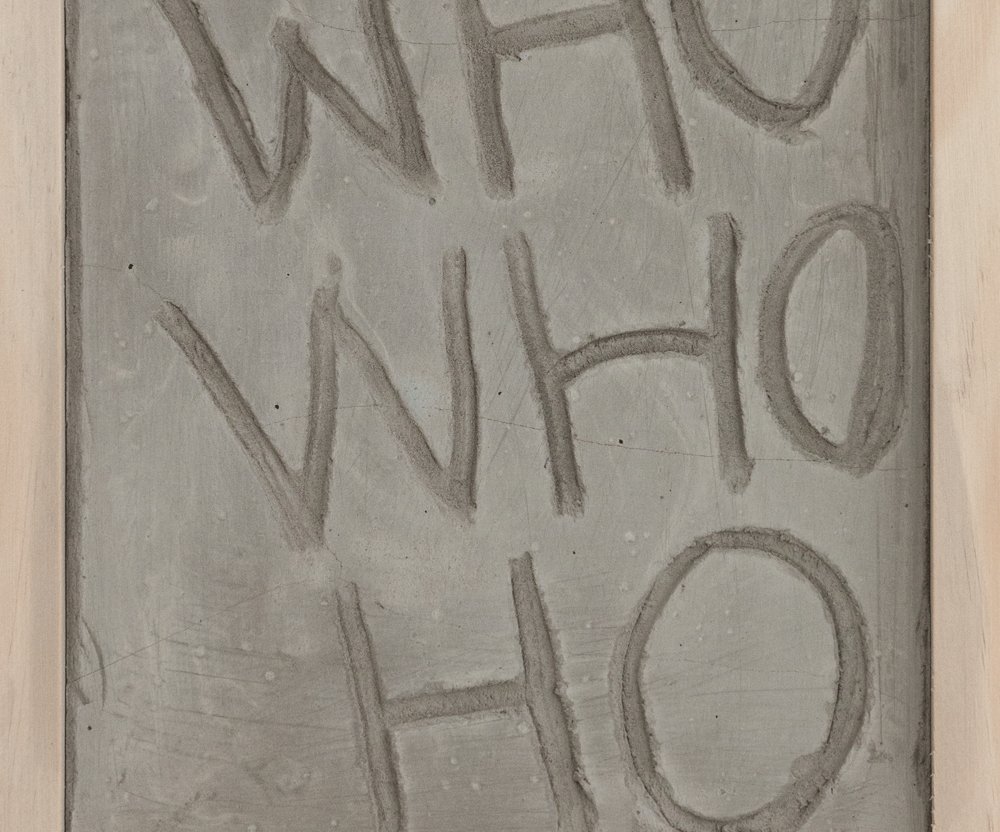

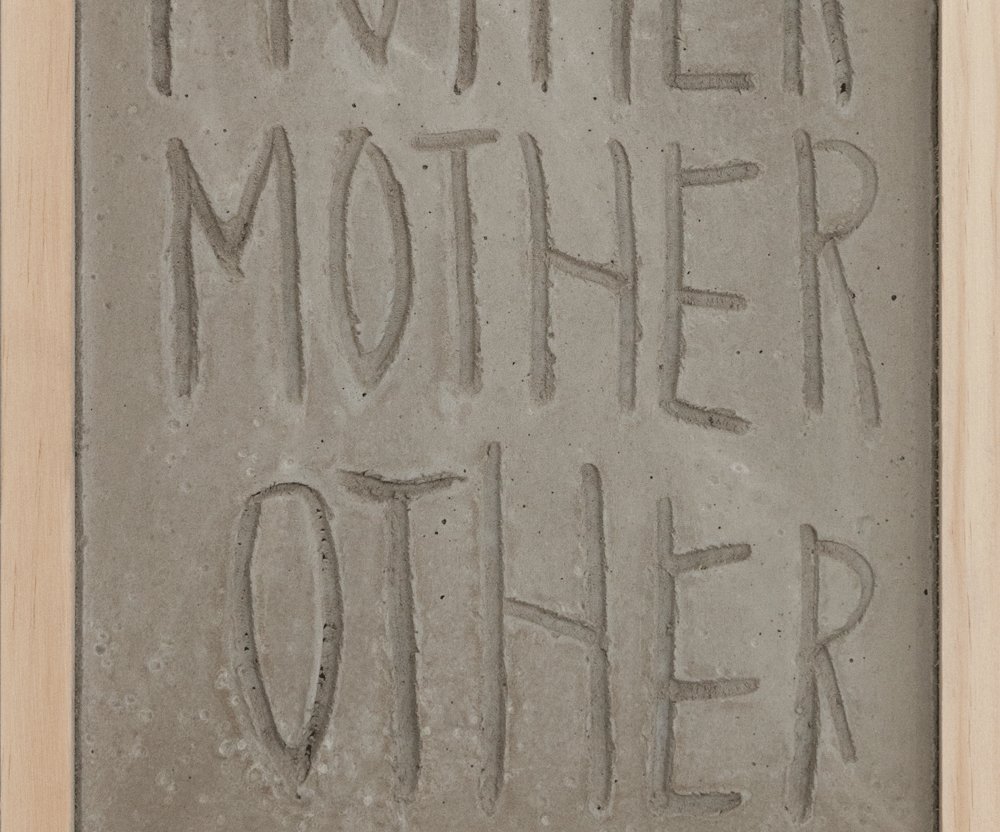

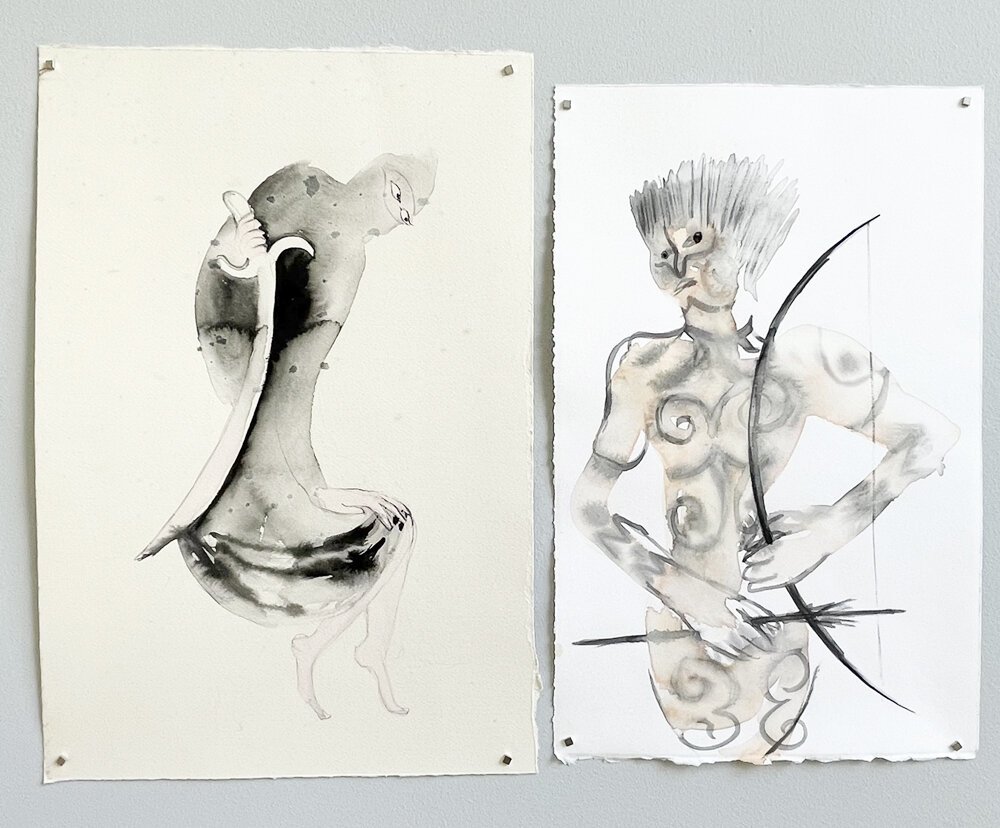

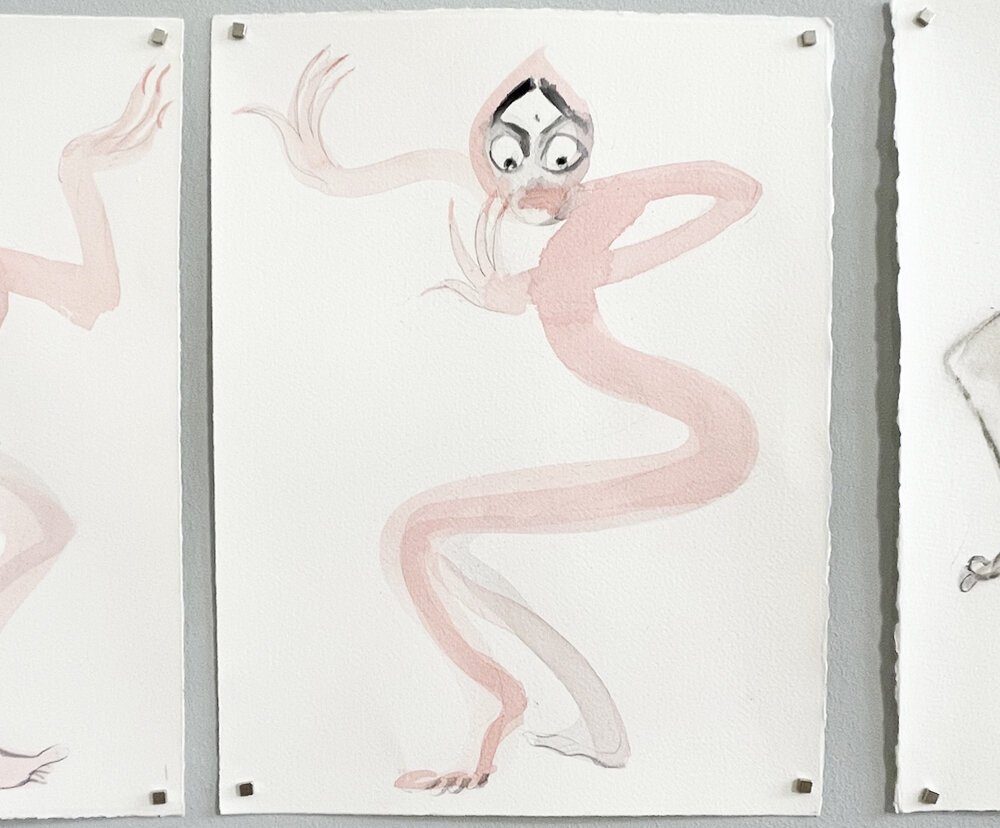

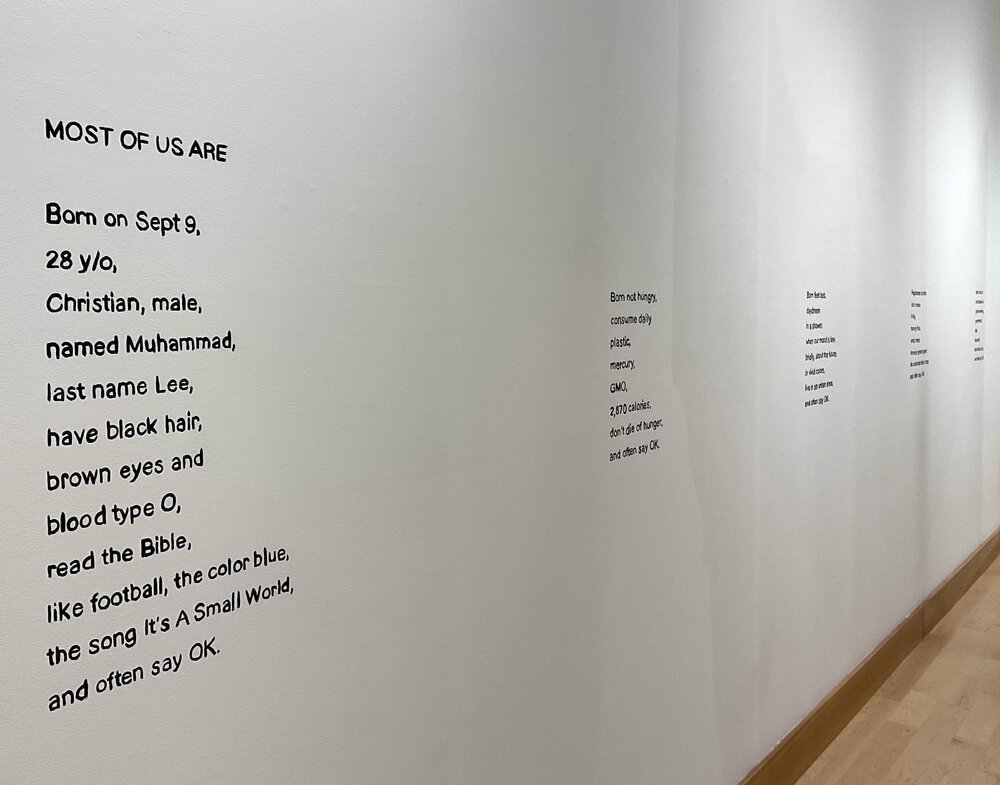

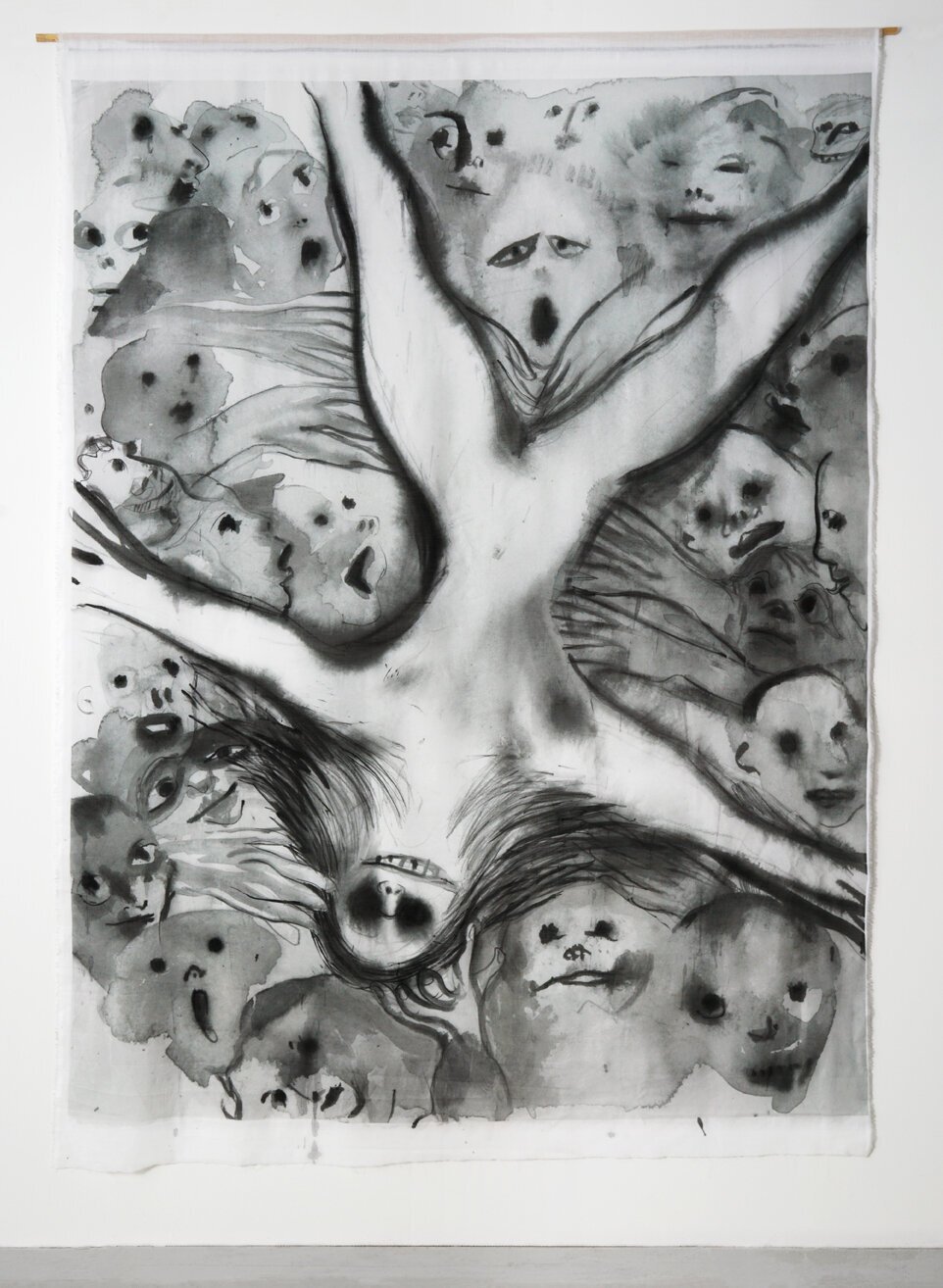

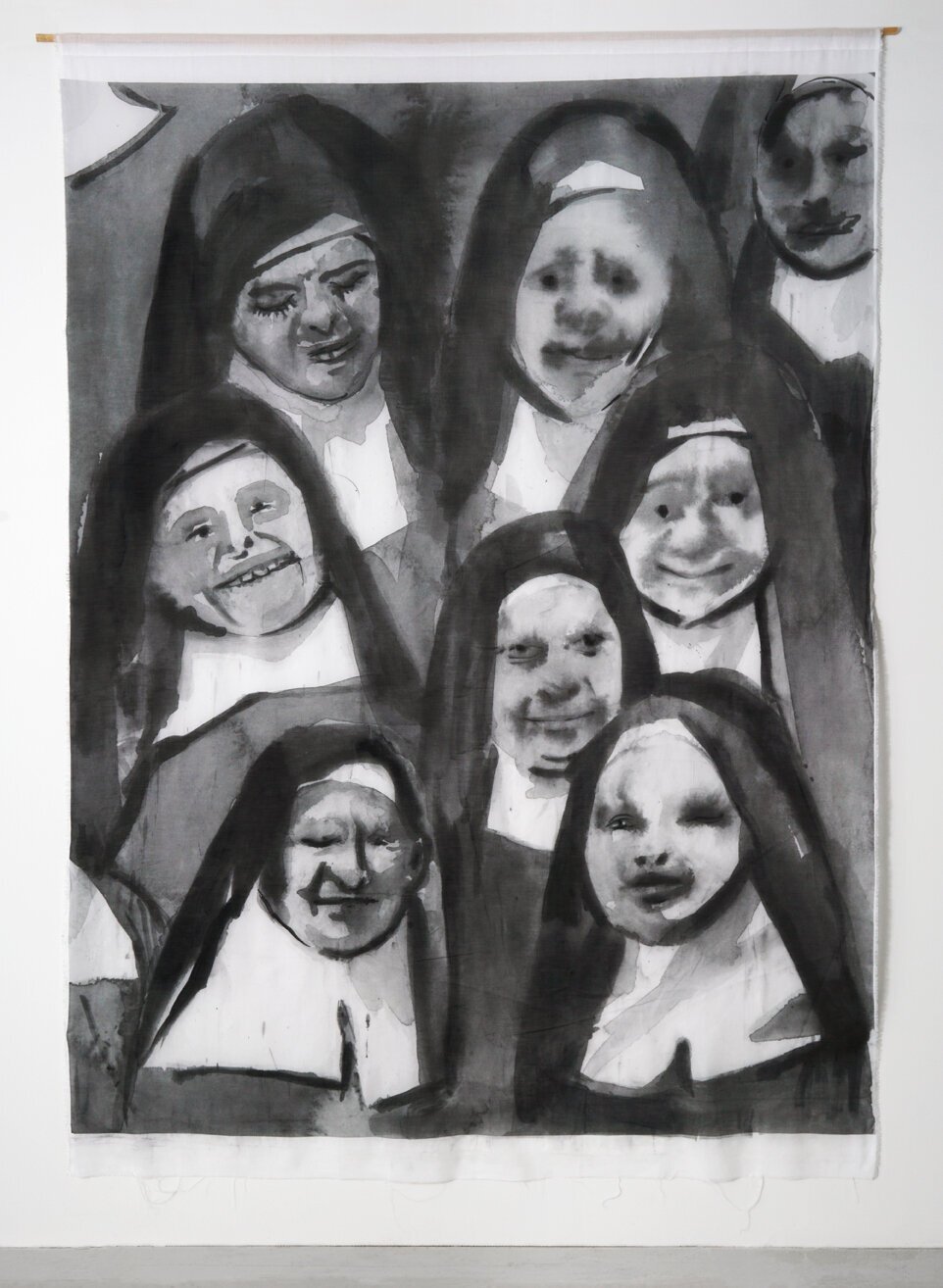

Visions, inspired by dreams, surrounding life, or drawn from the unconscious, are at the heart of Mia Enell’s paintings. She plays with words through images, her figures of speech are free associations on canvas. Loosely Knit is a literal rendering of its title: a system of interconnected discrete units freed from instrumental utility or significance. Alina Bliumis’ text-based sculptural works, Concrete Poems, recall street wall scribbles, graffiti, and absurdist poetry. They consist of words literally inscribed on tablets of wet concrete. Border/Order; Textile/Tile; Lover/Over: the playfulness of crossword puzzles often leads to unexpected existential interrogations. Usingreadymadeexpressionsorrepetitionsofasingleword, ElvireBonduelle utilizes a repertoire of images and objects with apparently joyful potential. Made of words carefully calligraphed -in her own hand-designed font- over colorful wave patterns, Bonduelle’s paintings revel in their own obviousness.

Analia Saban dissects and reconfigures traditional notions of painting, often using the medium of paint as the subject itself and the canvas as a medium rather than a support. Her methods such as unweaving paintings, laser-burning the canvas, molding forms or weaving paint through linen thread, remain central to her practice, as she continues to explore tangible materials in relation to the metaphysical properties of artworks. Julianne Swartz articulates an architecture of frailty. When viewed, her sculptures are activated slightly, at times, they even appear to breathe. Zero blanket is a silent tapestry, made from hair-thin copper wire. The tenuous lines from the irregularly weaved structure delineate and hold space until emptiness becomes substance. Zero Blanket embodies invisible presence and tangible absence, it engages a palpable vulnerability.

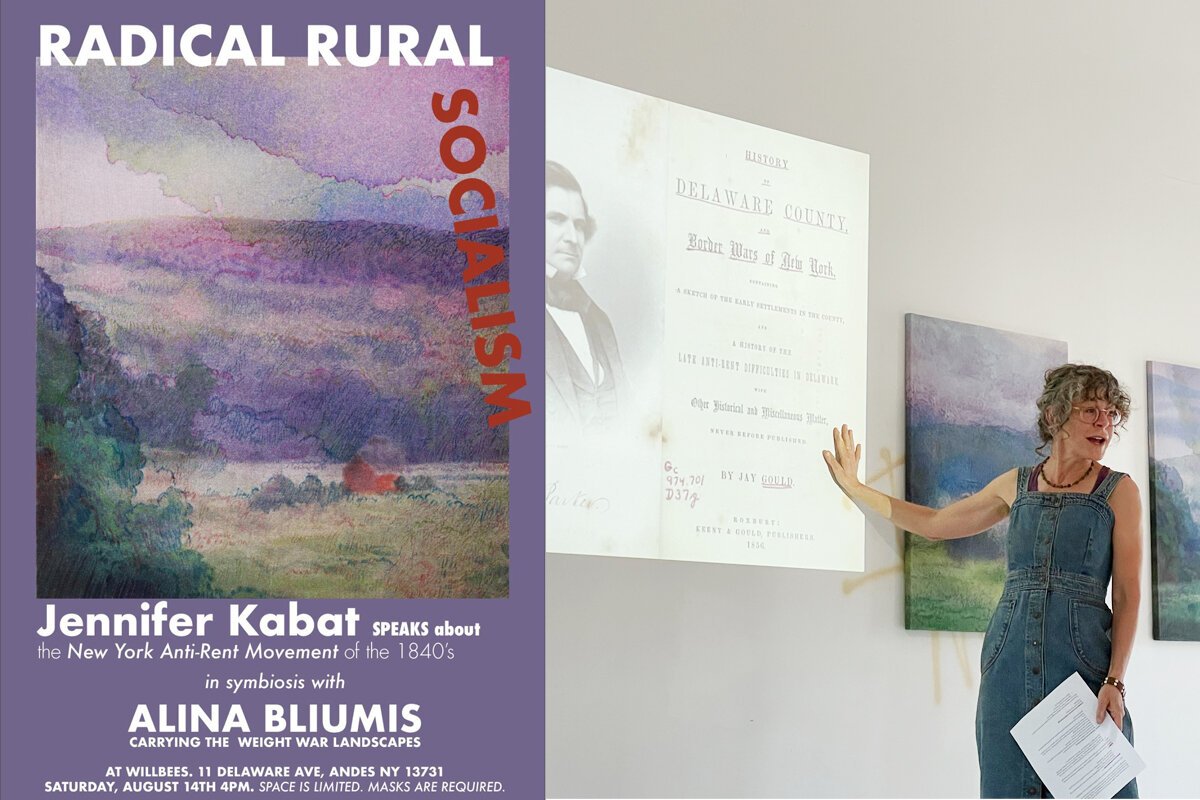

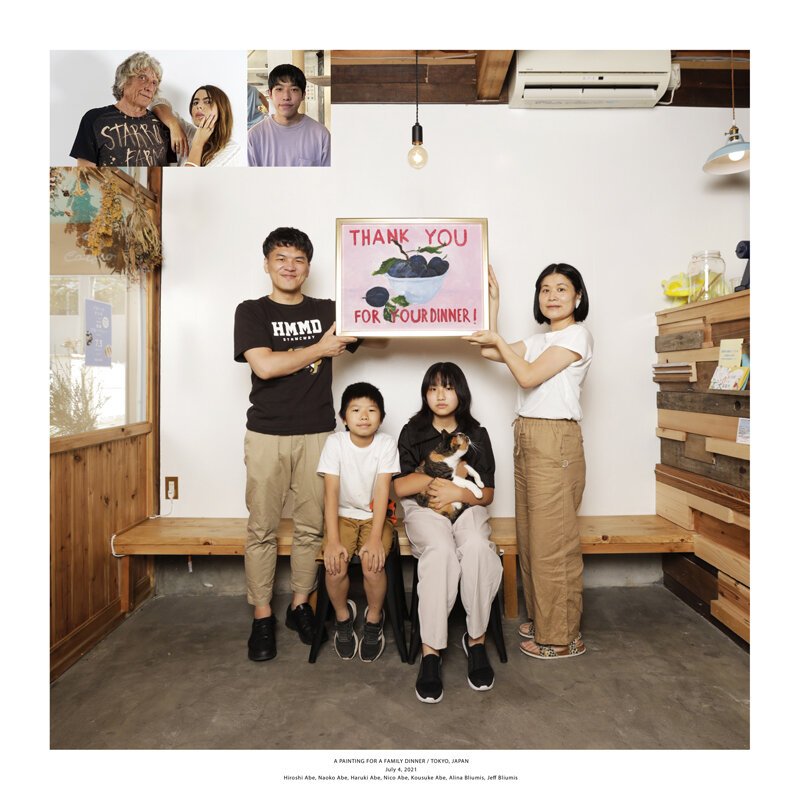

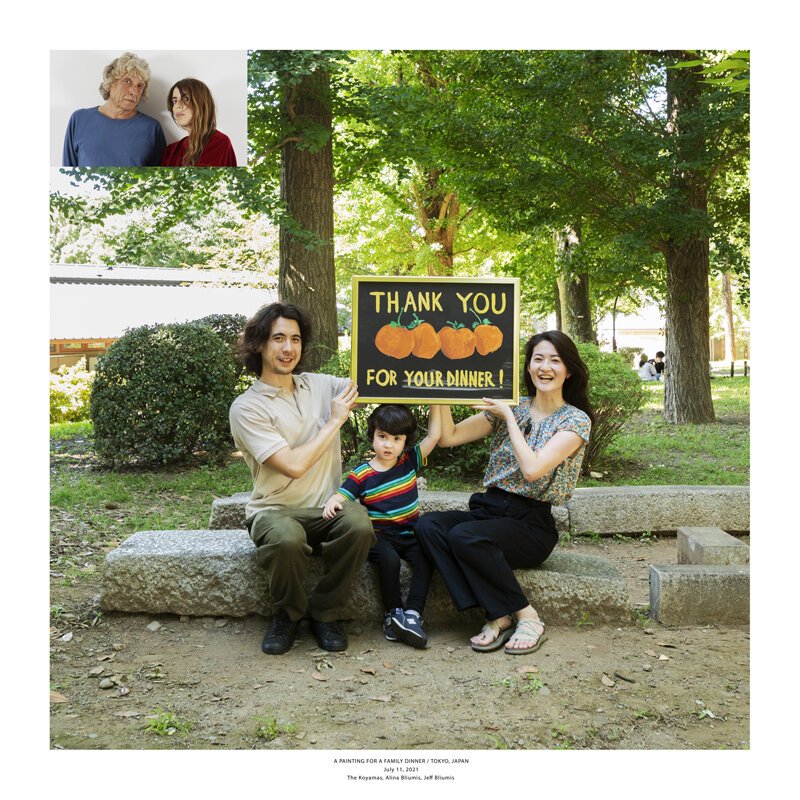

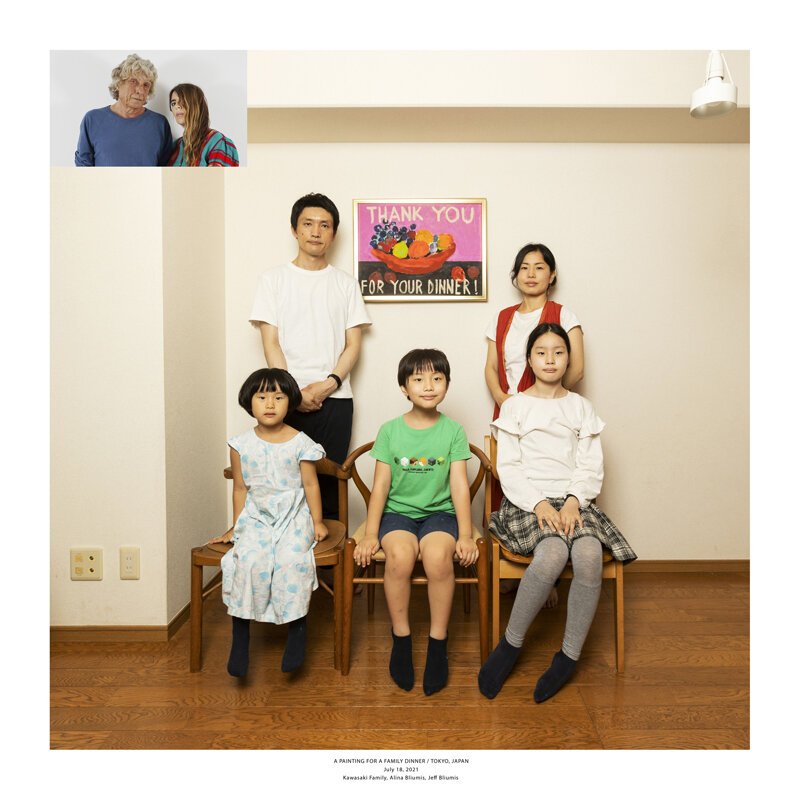

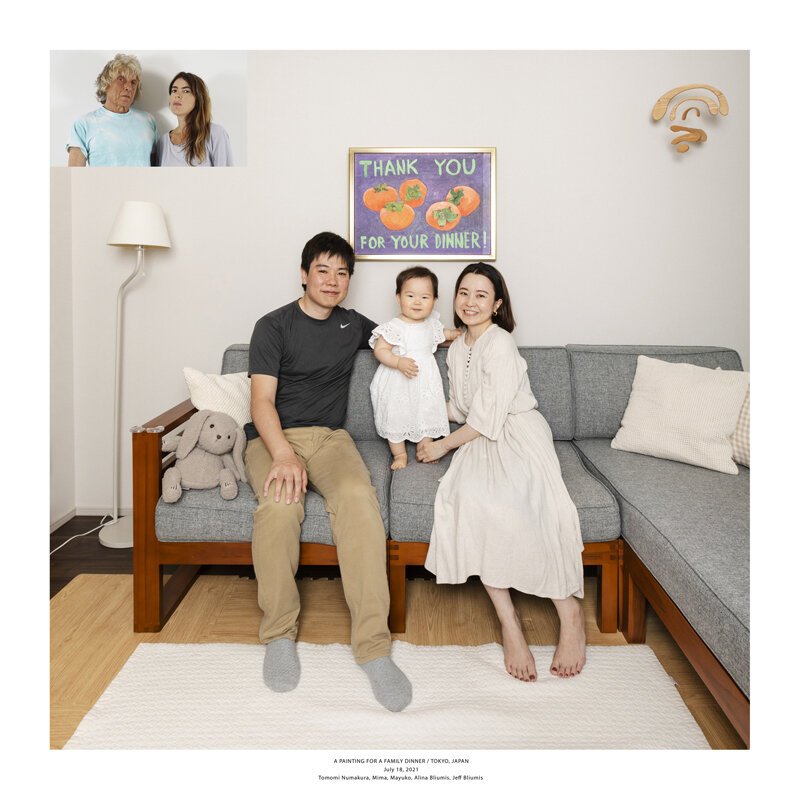

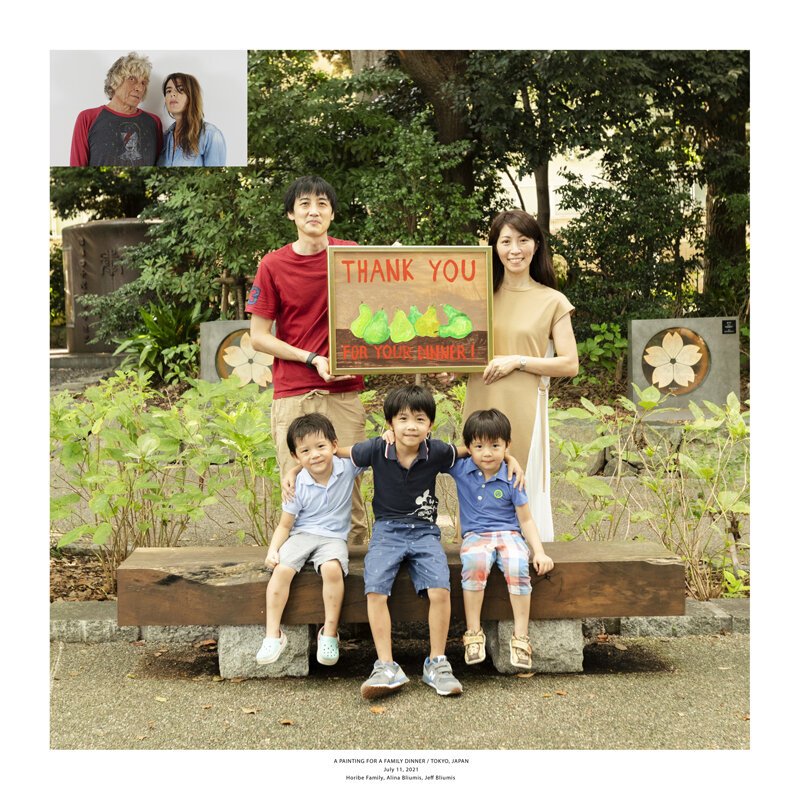

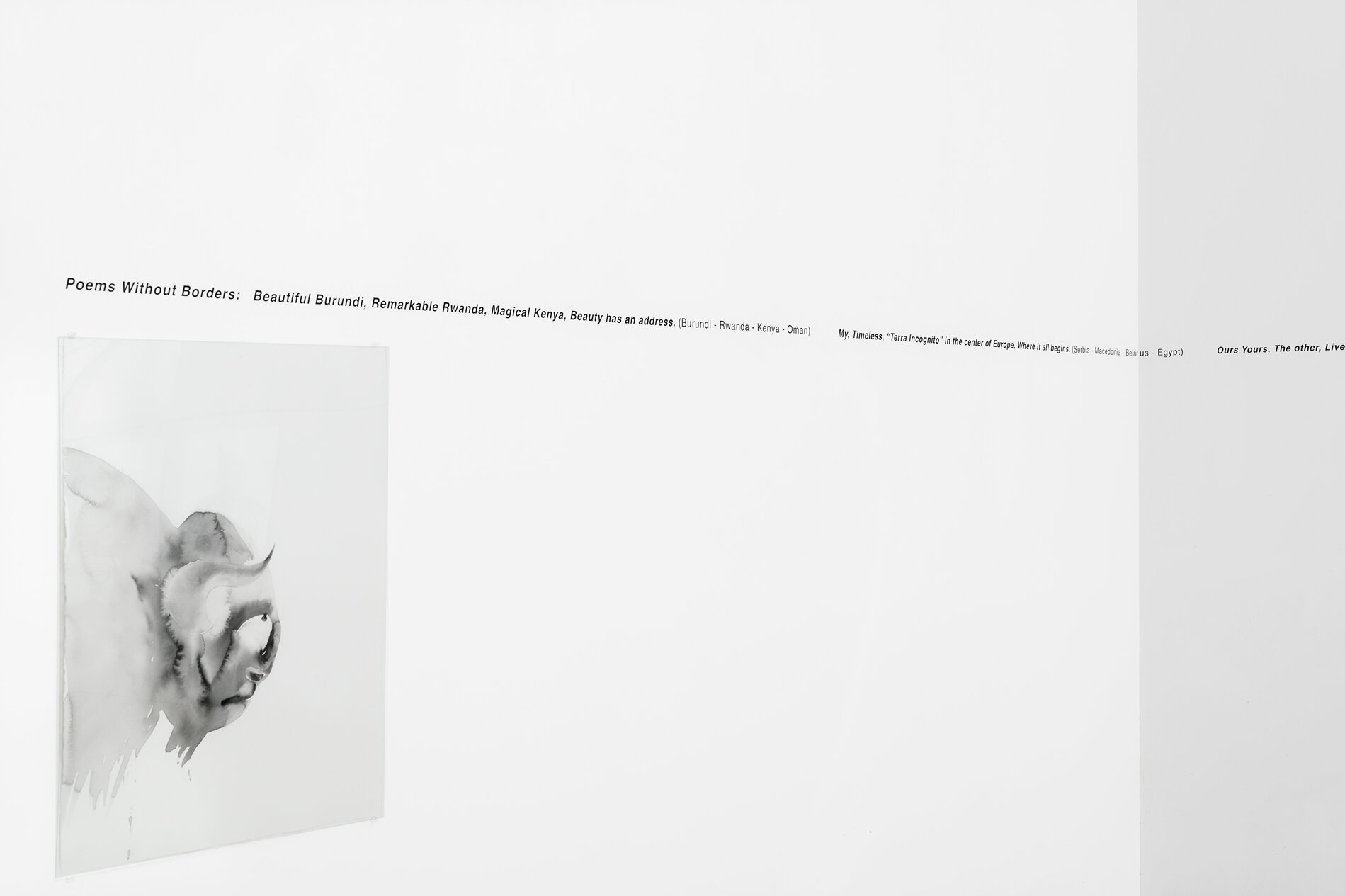

Alina Bliumis BORDERS AND BRUISES Anna Zorina Gallery Los Angeles, CA, June 2 - July 9, 2022

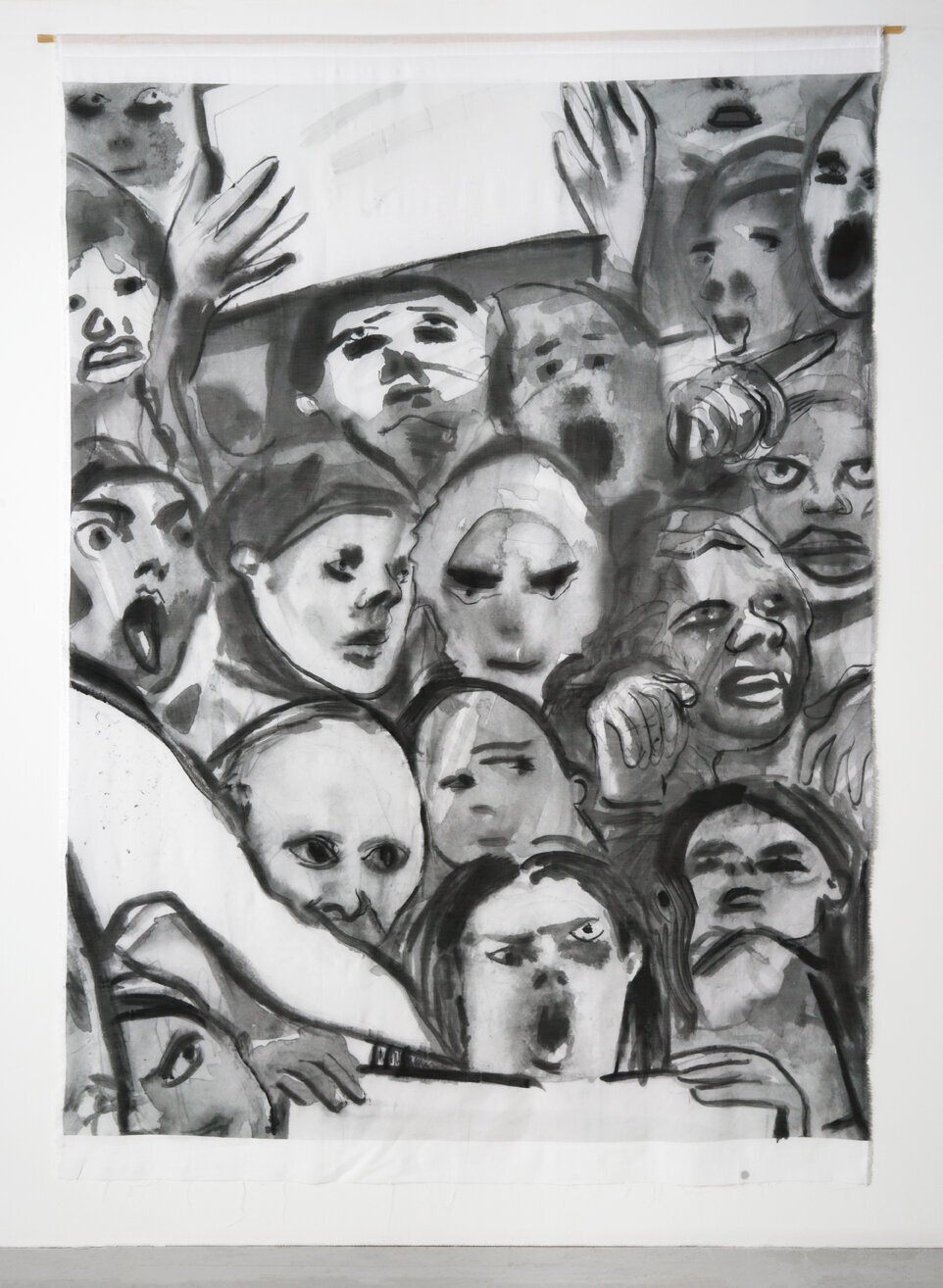

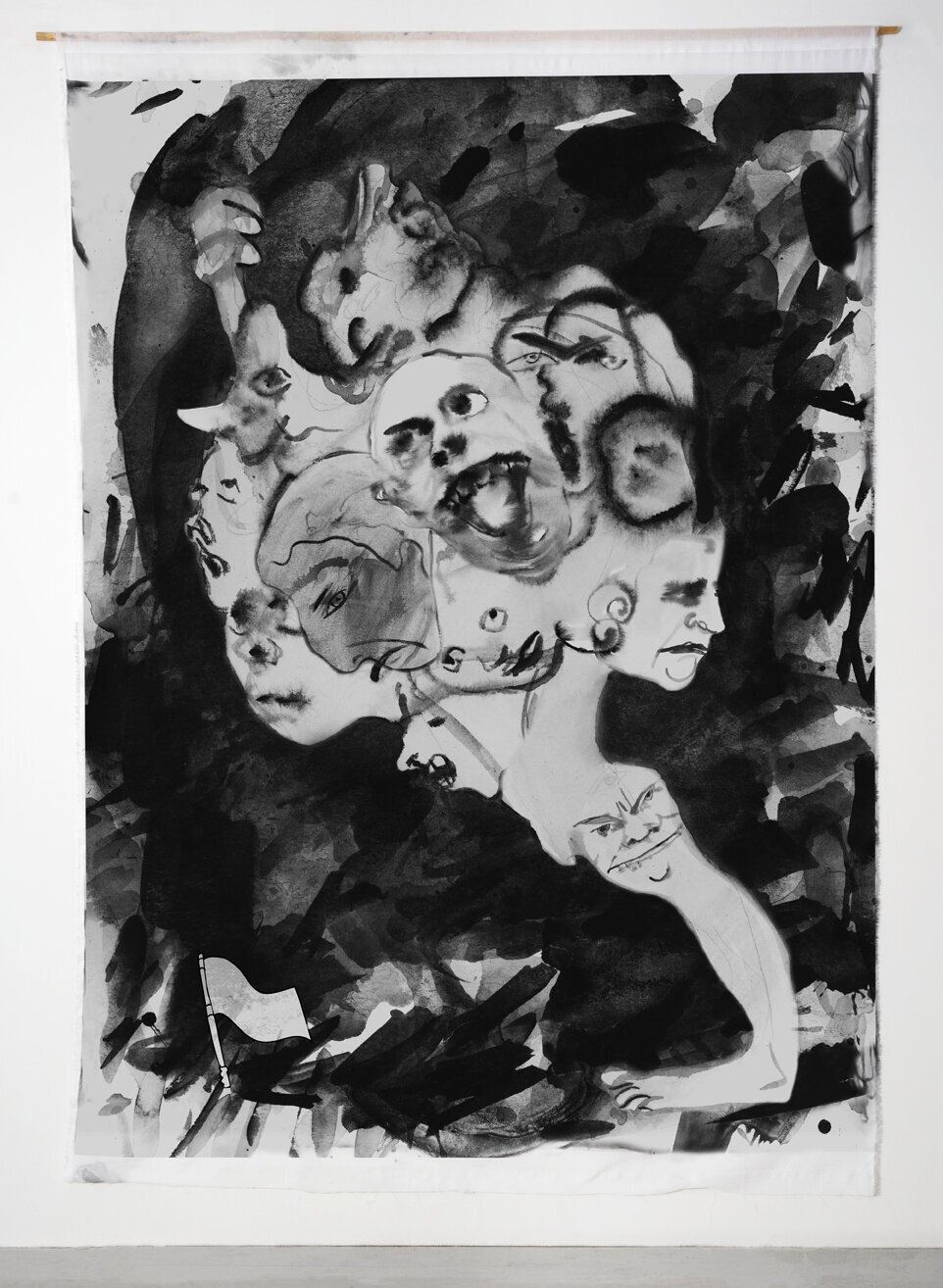

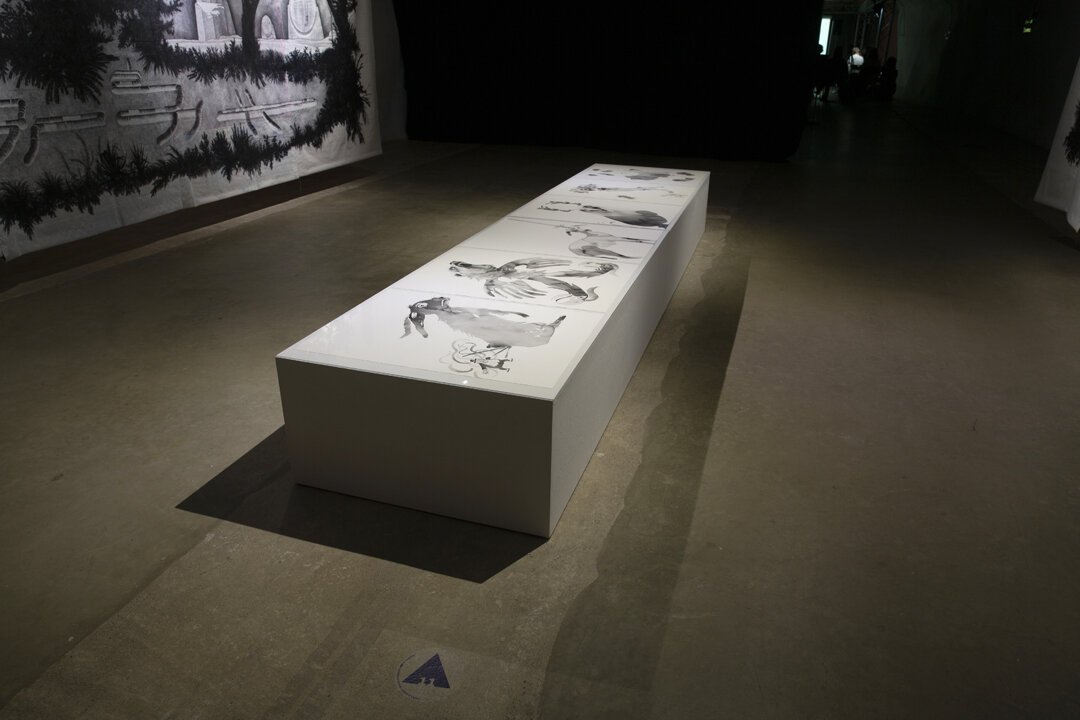

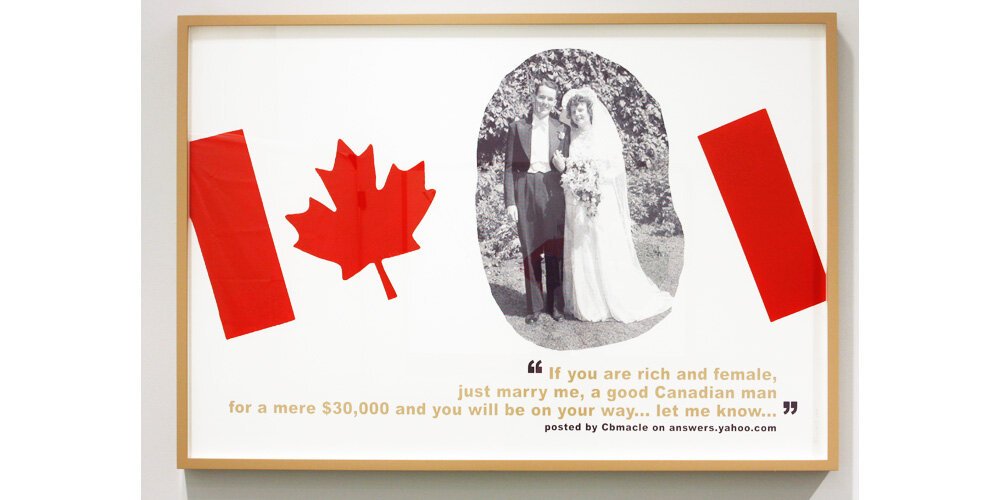

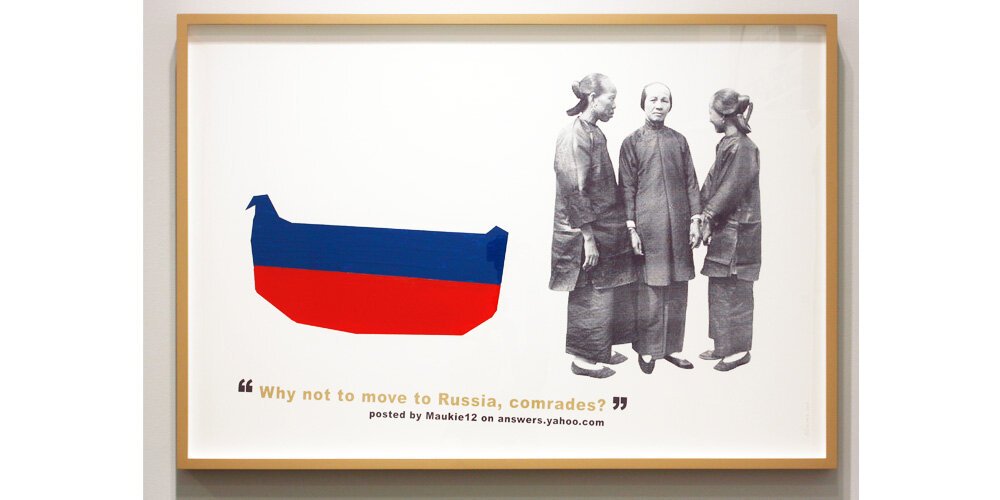

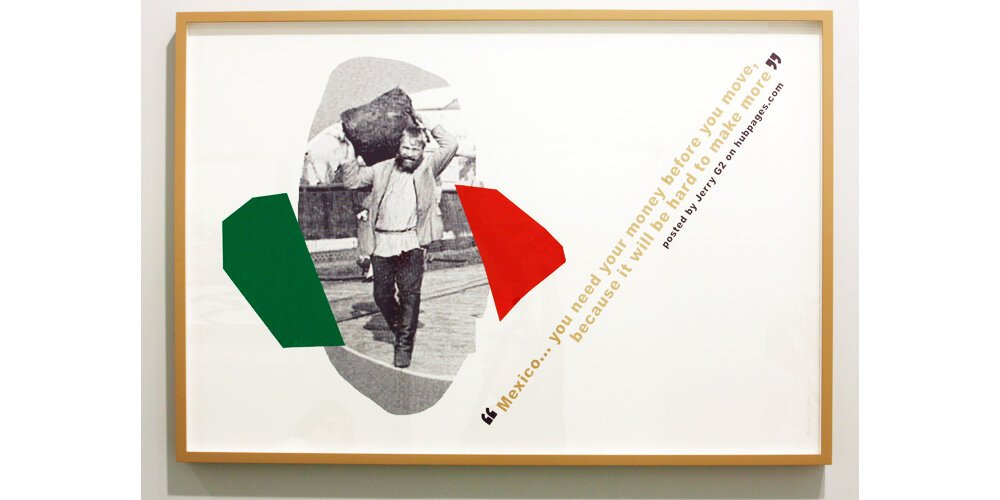

Anna Zorina Gallery is pleased to inaugurate its new Los Angeles Gallery space with the solo exhibition of Alina Bliumis, Borders and Bruises. This is Bliumis’ first show with the Gallery. The exhibition will feature three bodies of work including the watercolor maps of Nations Unleashed, the abstract paintings series Bruises and text-based sculptural works Concrete Poems. A percentage of proceeds from the exhibition will be donated to Direct Help For Ukraine and BYSOL, an organization supporting politically repressed Belarusians.

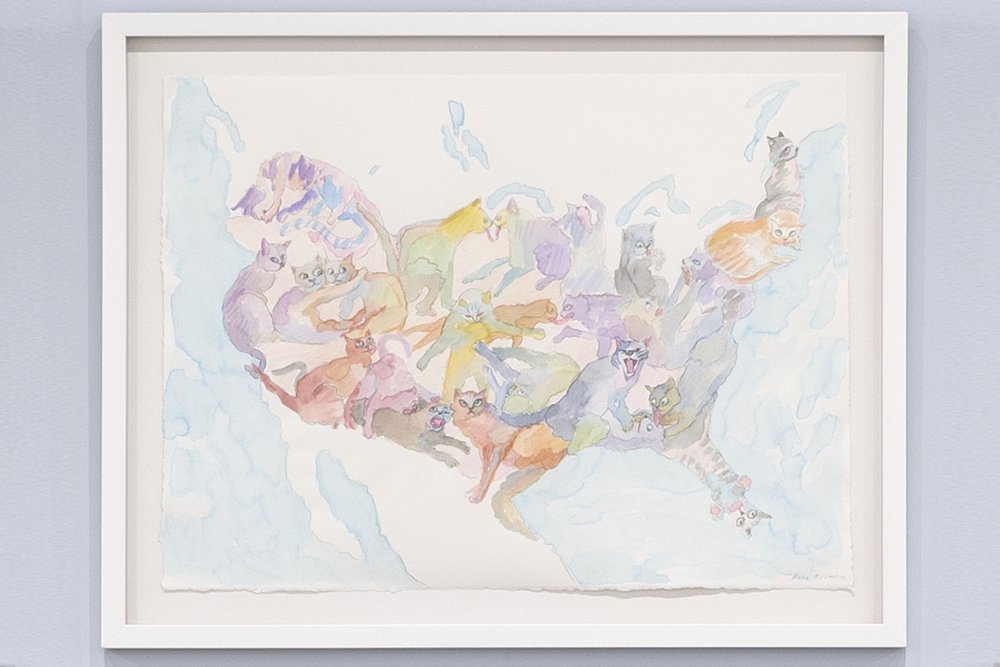

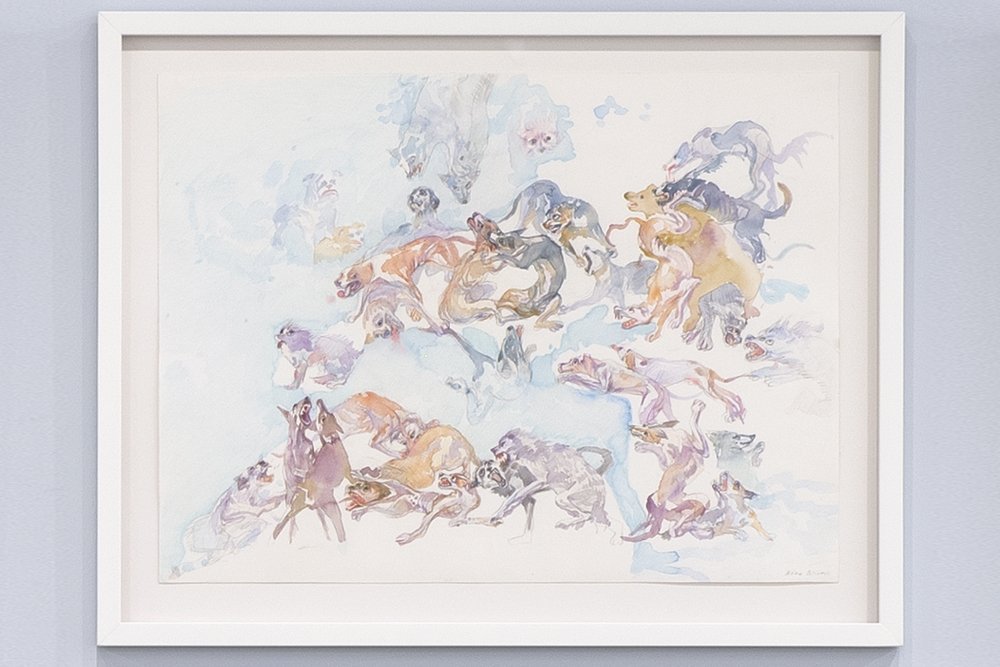

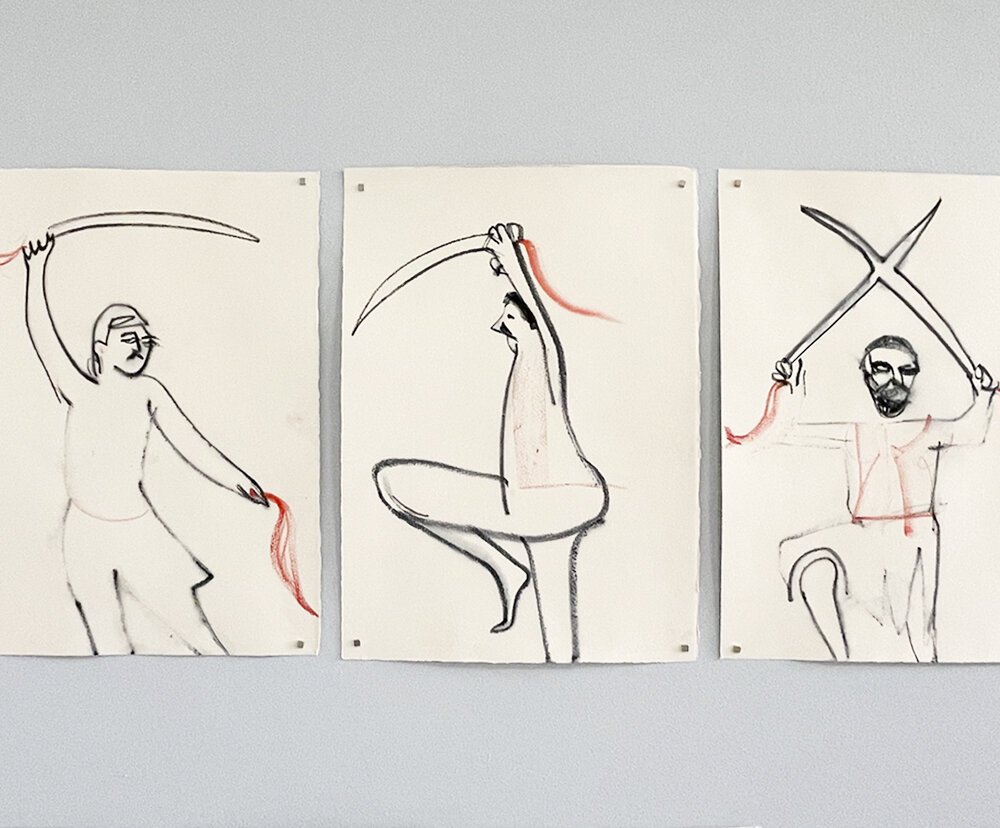

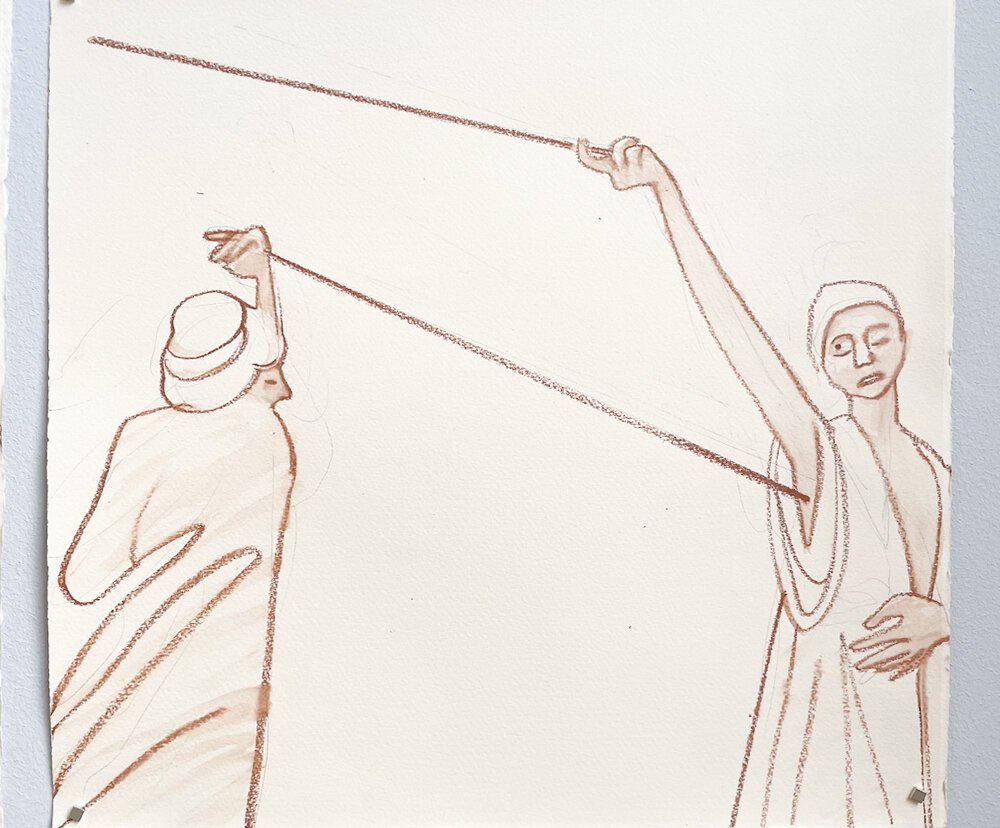

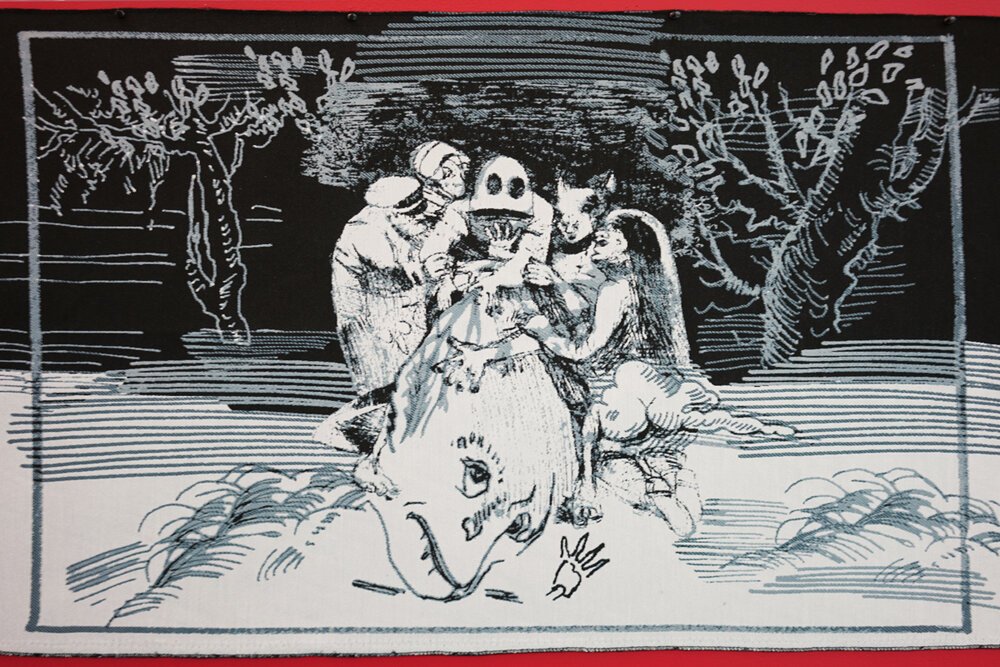

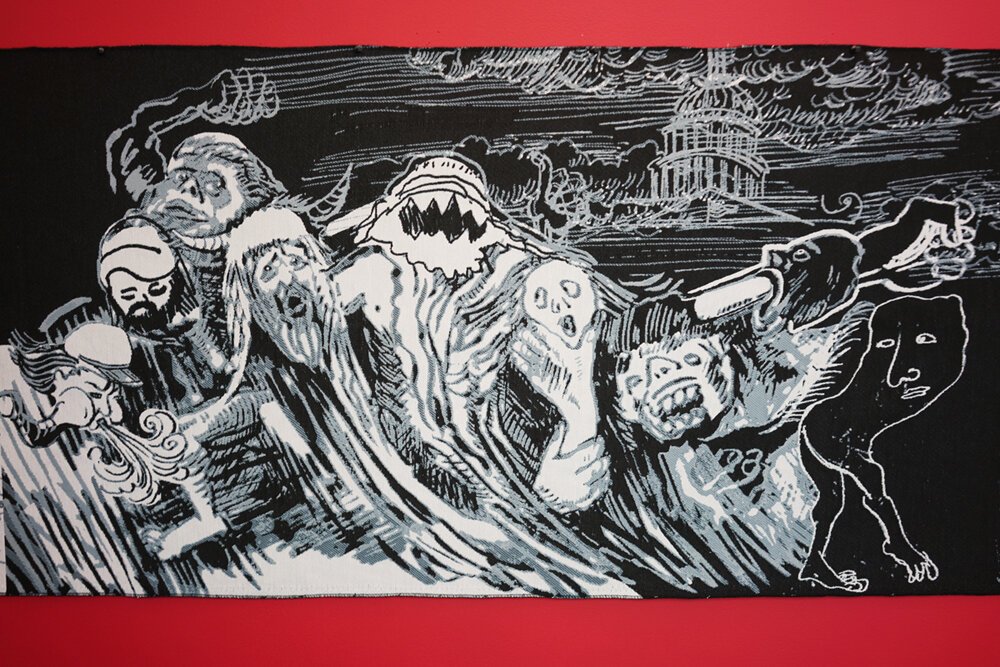

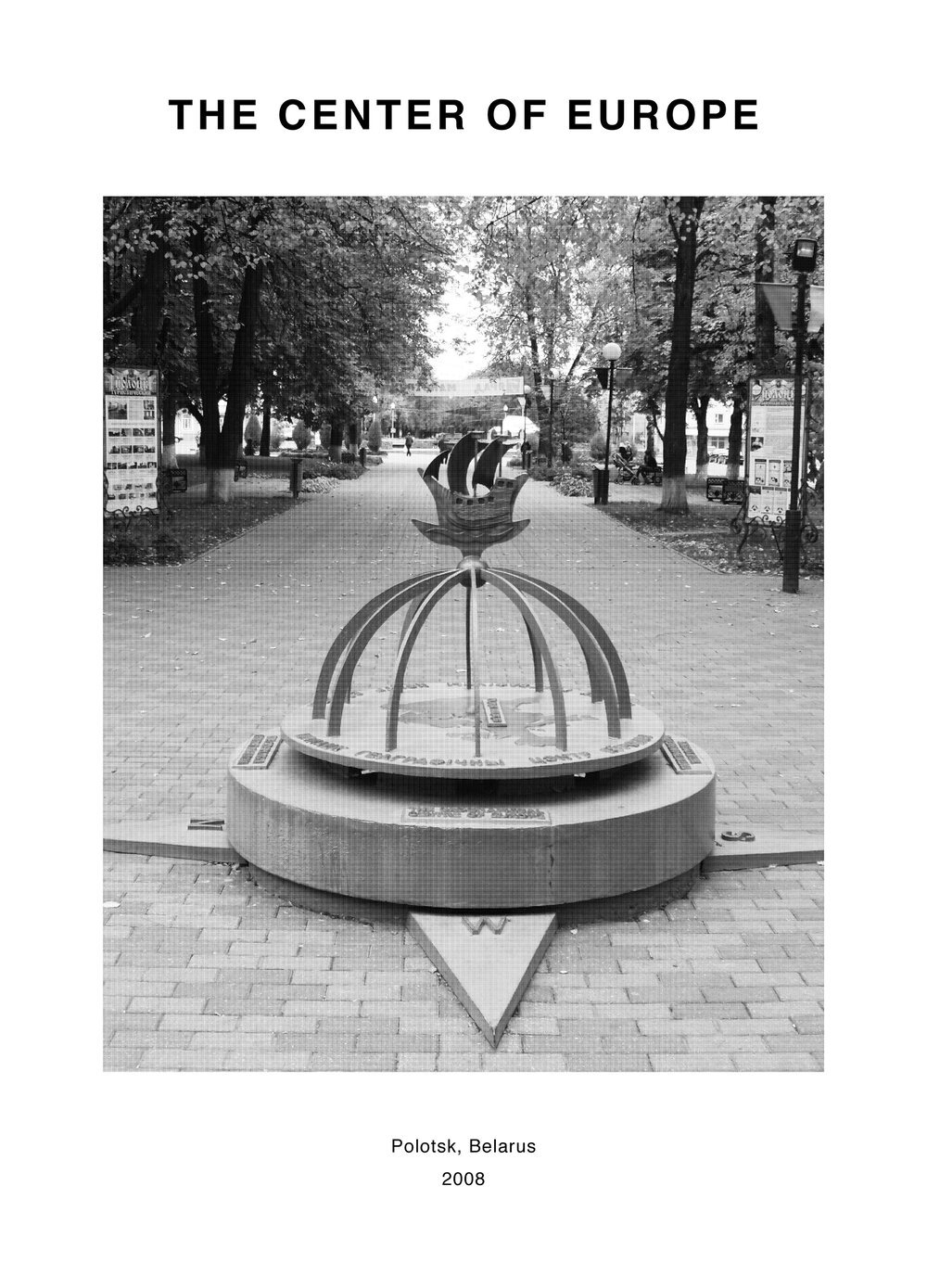

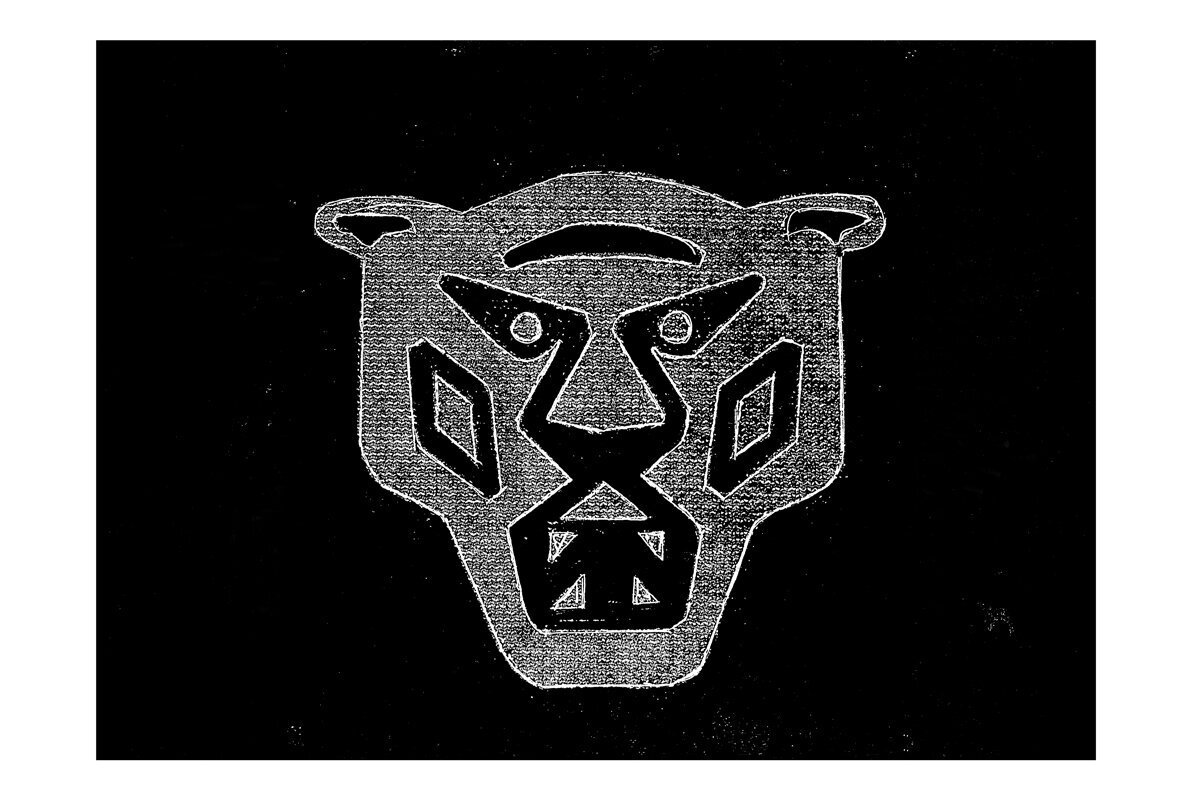

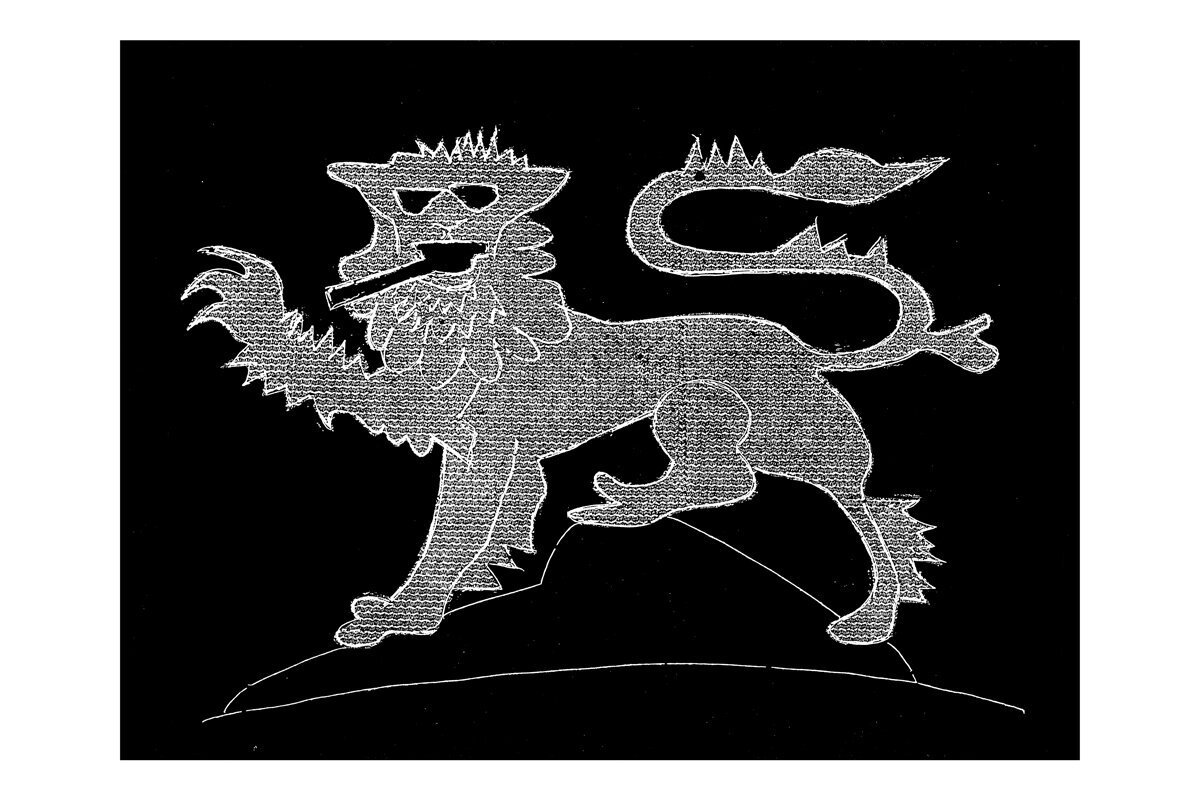

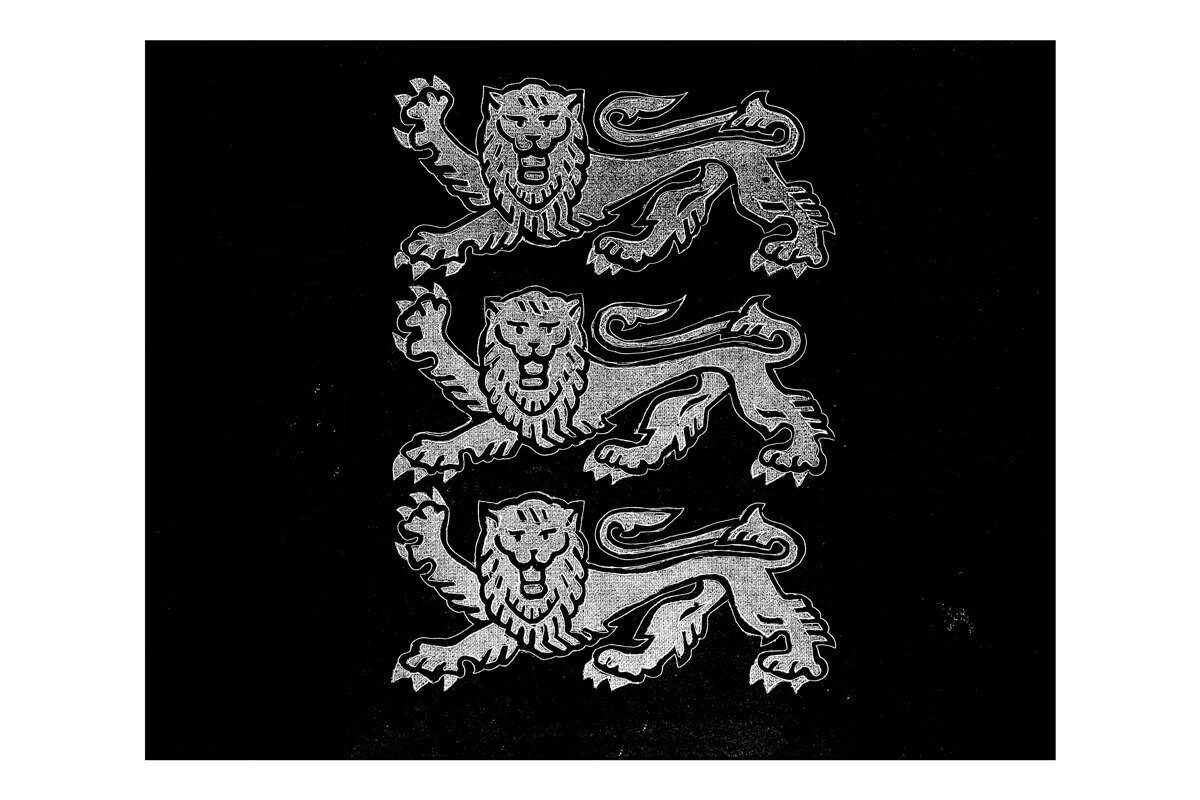

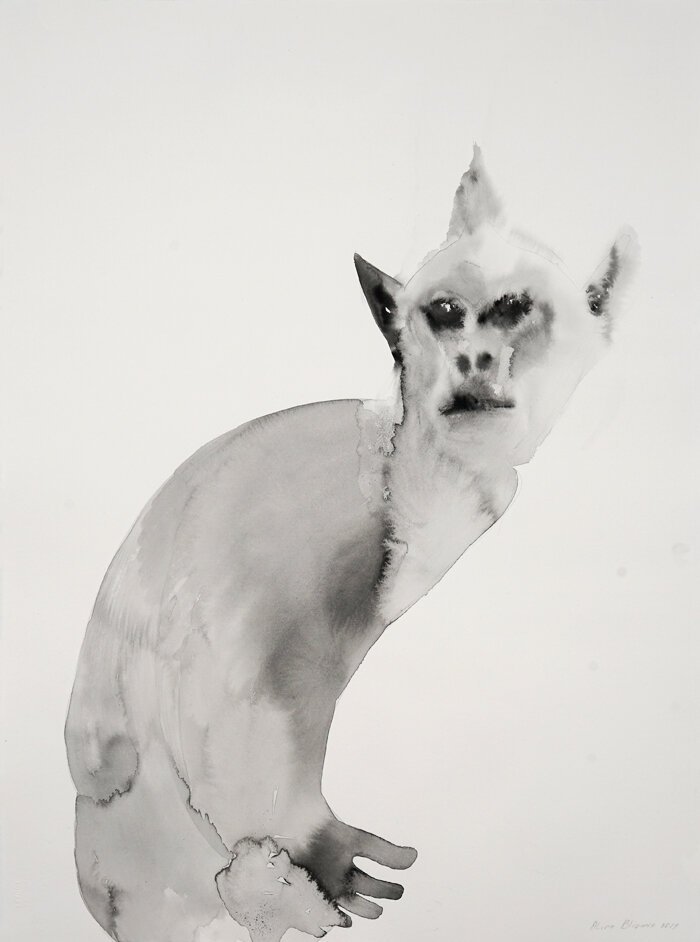

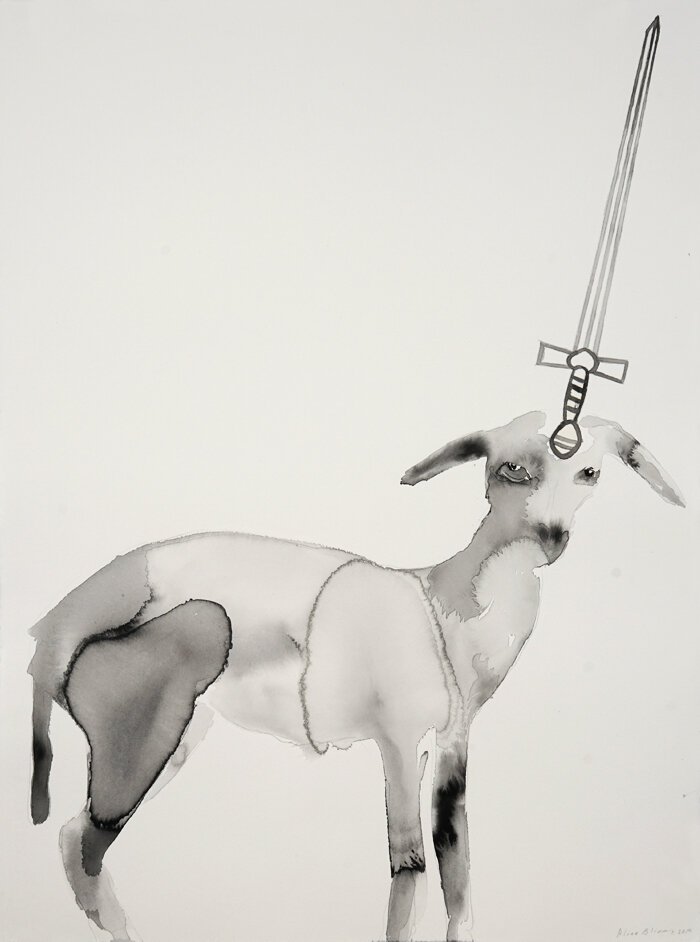

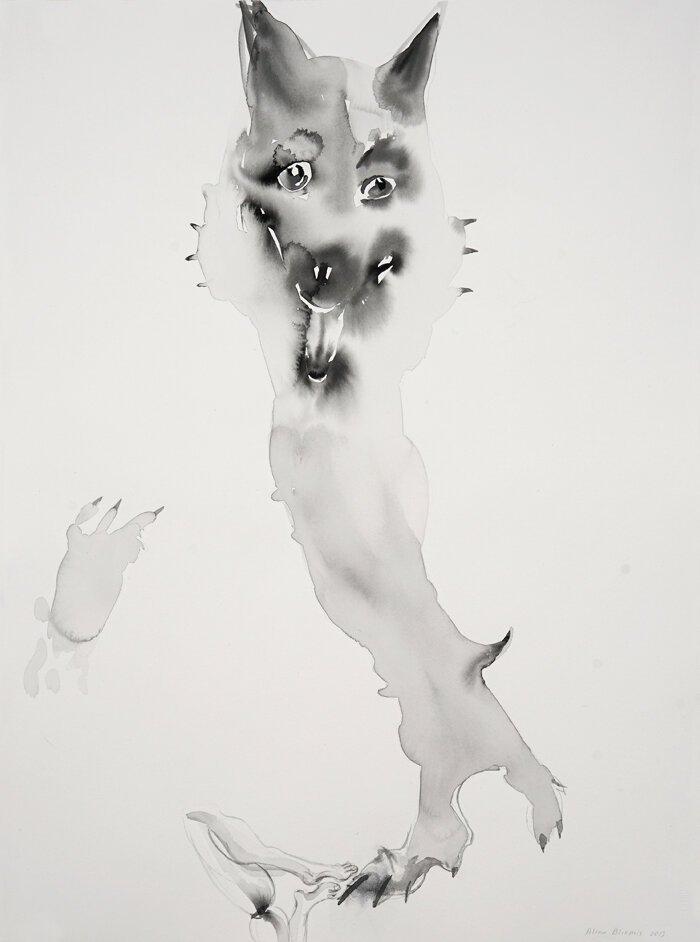

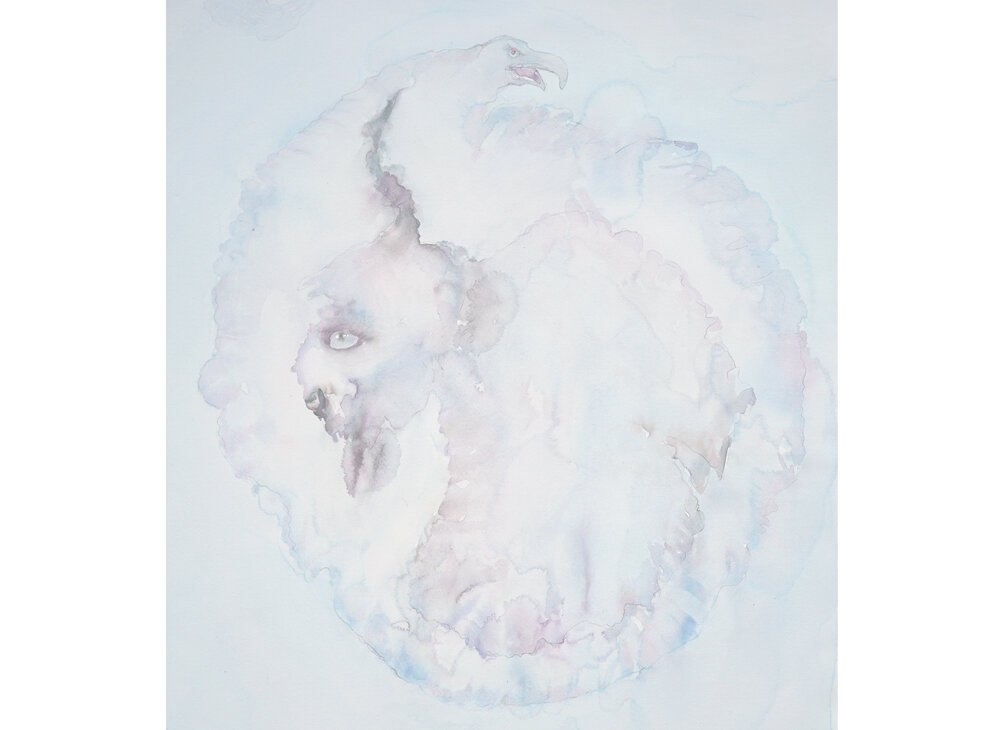

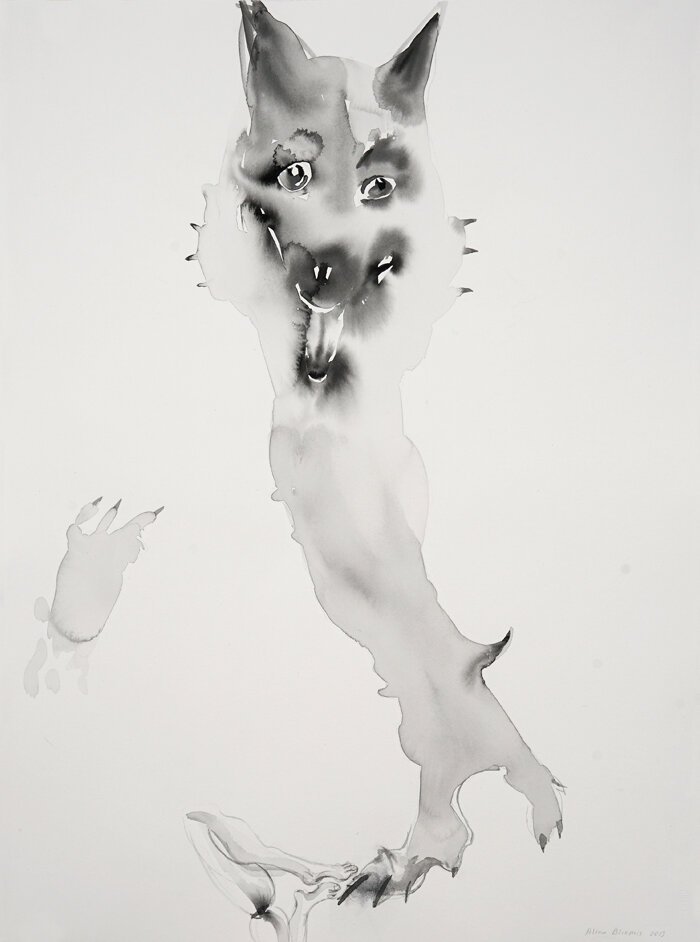

Bears, eagles and octopi have been active role-players in satirical maps since the 16th century. With her watercolor series, Nations Unleashed, Bliumis pays homage to cartographic curiosities by employing animal symbolism to convey biting political critique. In Bear vs. Nightingale, European countries become a battleground of zoomorphic shapes. Here the national animals are seen in mid-clash as the Ukrainian nightingale faces the Russian bear, an eagle representing the West stands alert. Bliumis explores this history of transferring human actions and motives onto primal beings to remove individual responsibility and agency from the political theater. This shift in perspective heightens awareness to this rampant strategy of displacement, compelling us to critically reflect on the Mine line that separates fact from fiction in global geopolitics.

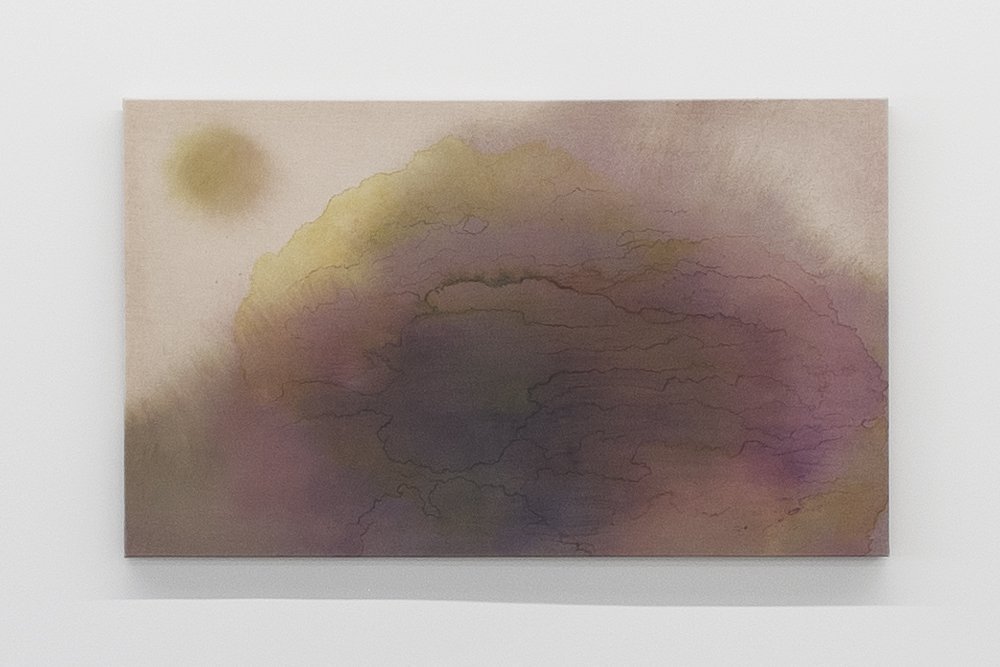

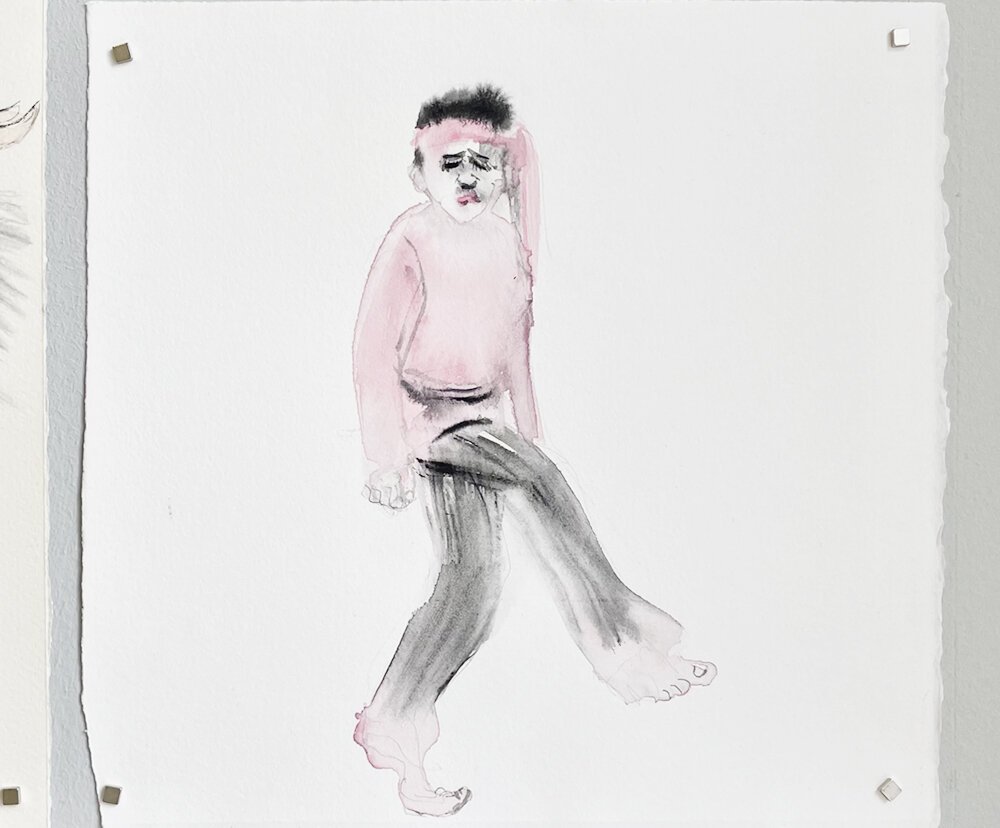

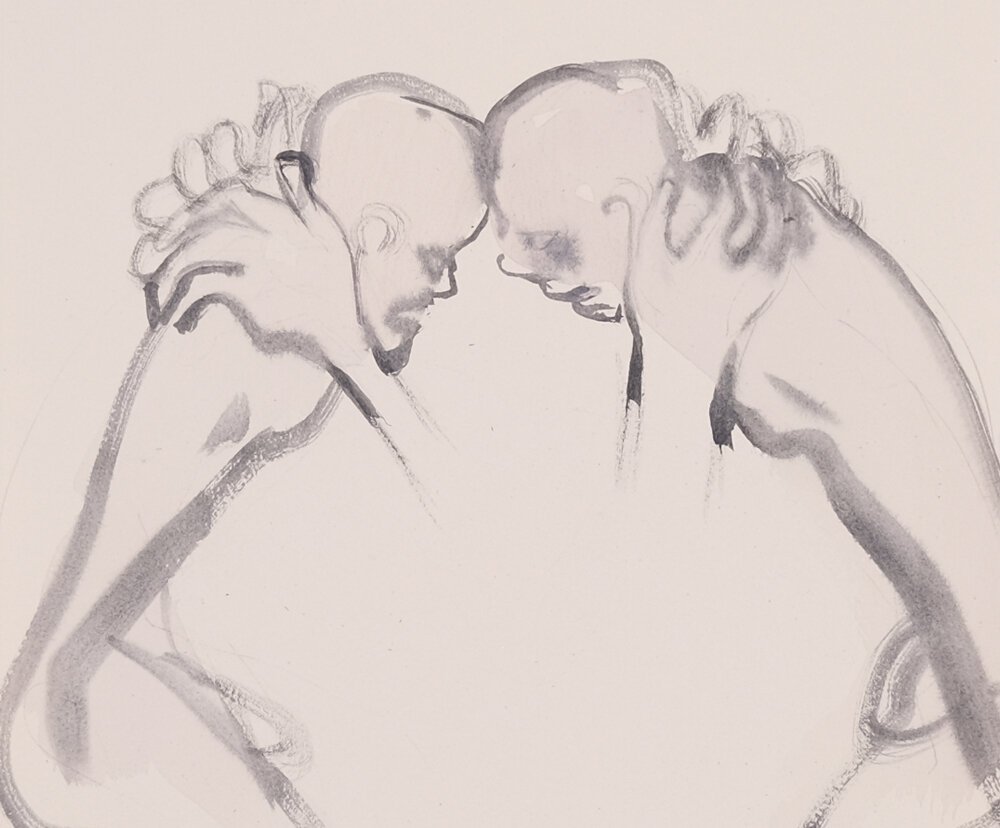

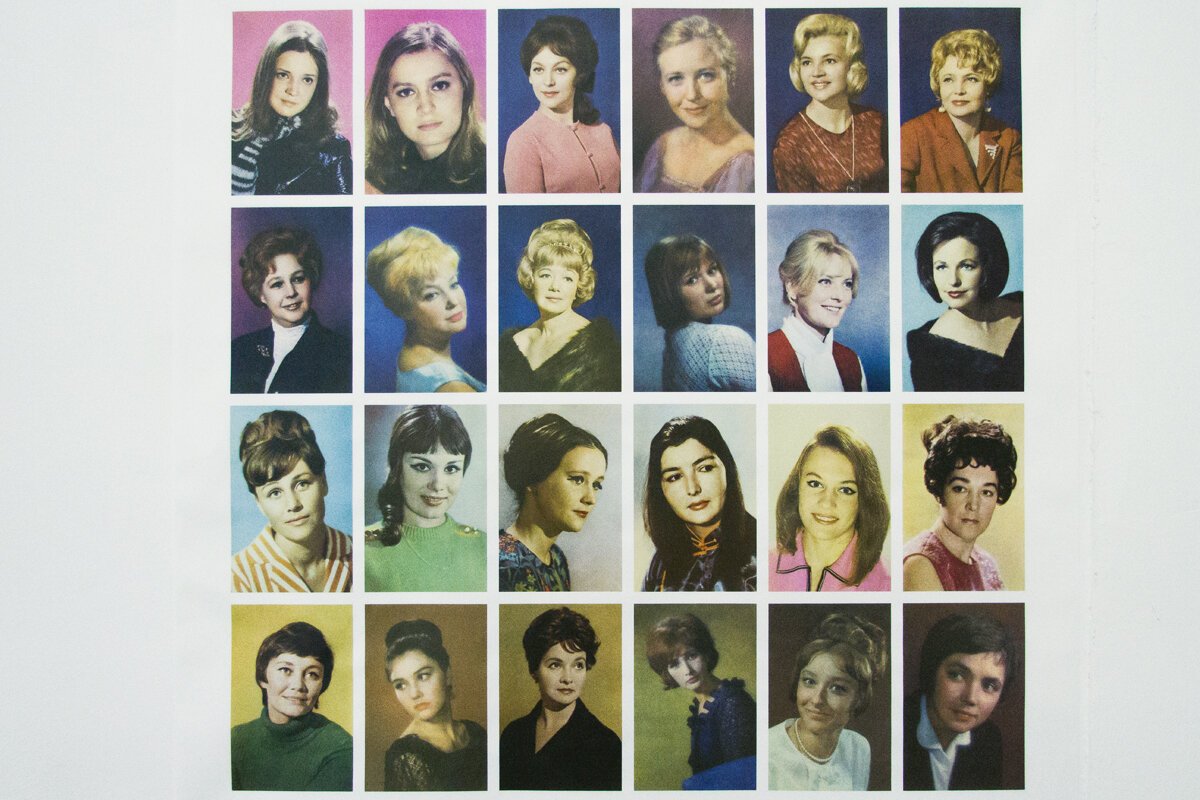

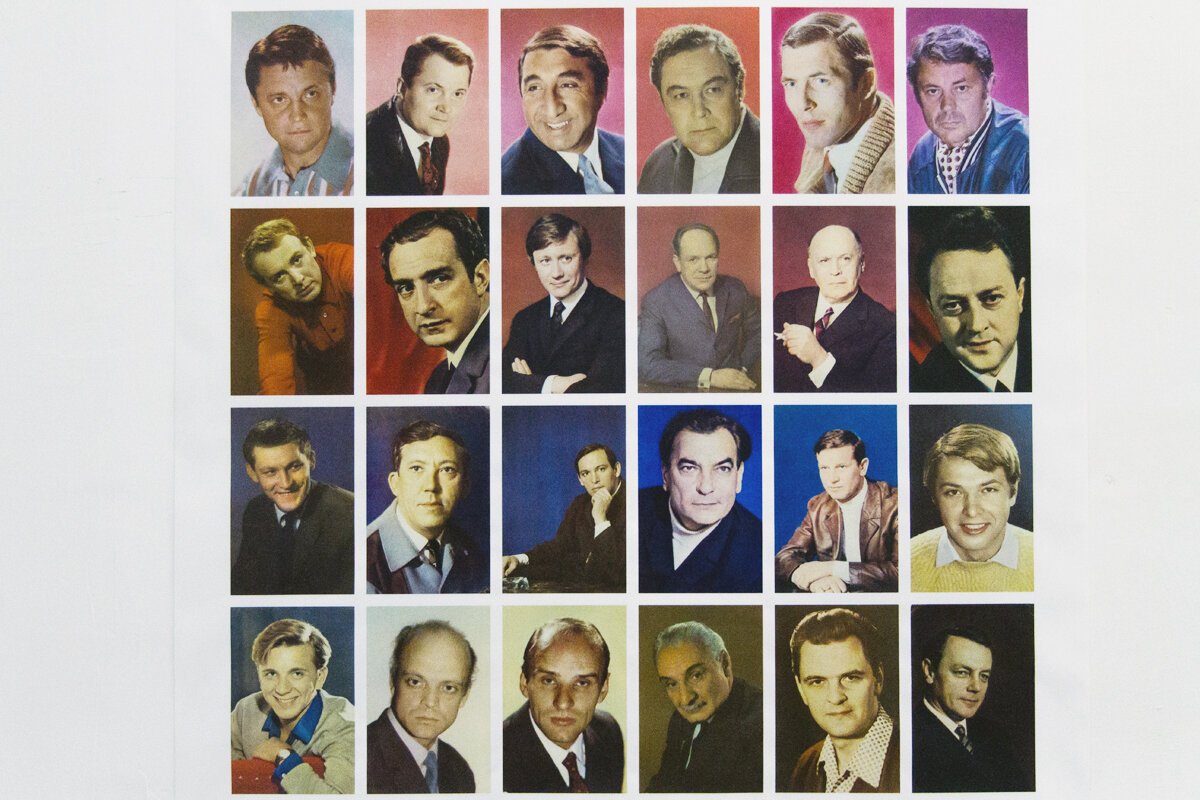

Before maps are drawn, history is first recorded on bodies through experience captured in the form of bruises, wounds, calluses. The body is a document of social struggles. For example, in the artist’s native country of Belarus, the nation united in response to the rigged election of 2020. These protestors shared the resulting scars of having faced aggressive measures of suppression and brutal detainment across various media platforms, bringing public awareness to the human rights abuse in hopes of achieving justice in the future. These events have triggered Bliumis’ watercolor on linen series, Bruises. Each bruise painting is numbered in reference to statistics of human suffering. The traumas range from serious to playful, from political prisoners and refugees to unrequited celebrity crushes. The artist represents the bruises as abstract patches of watercolor allowing the pigment to bleed into the weave of the linen in a style reminiscent of Color Field painting. Bliumis engages the expressionist style’s association with making an emotional impact through clarity of color and form with an emphasis on celebrating individual expression and freedom of subjectivity. Her paintings are spatial and alive to endow an immortality to the feelings and sensations that underlie these important moments throughout our own personal and collective history.

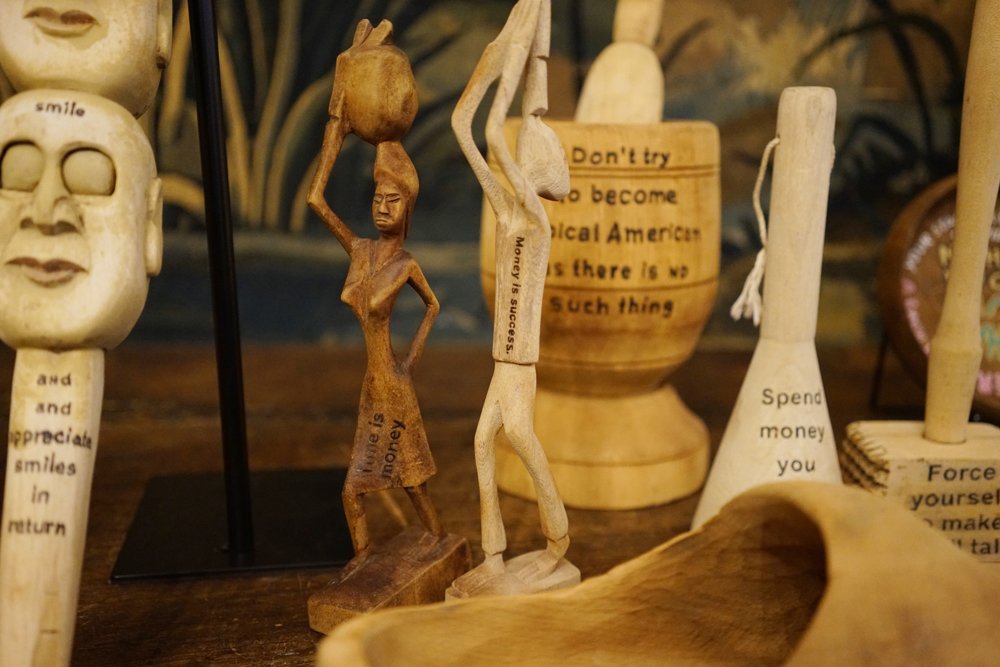

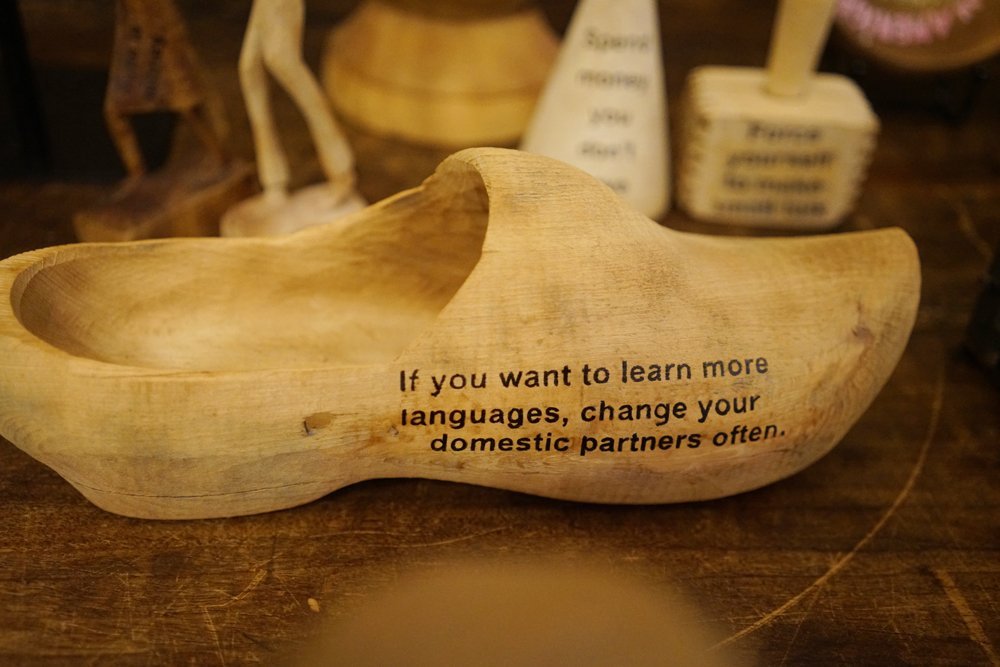

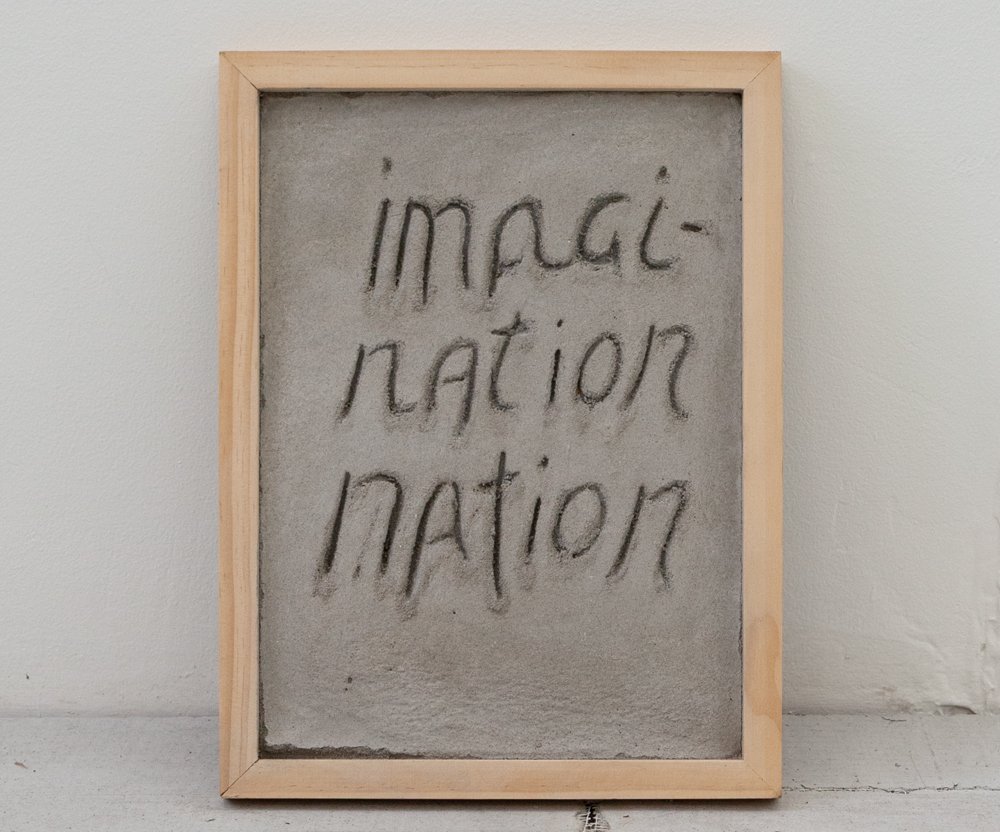

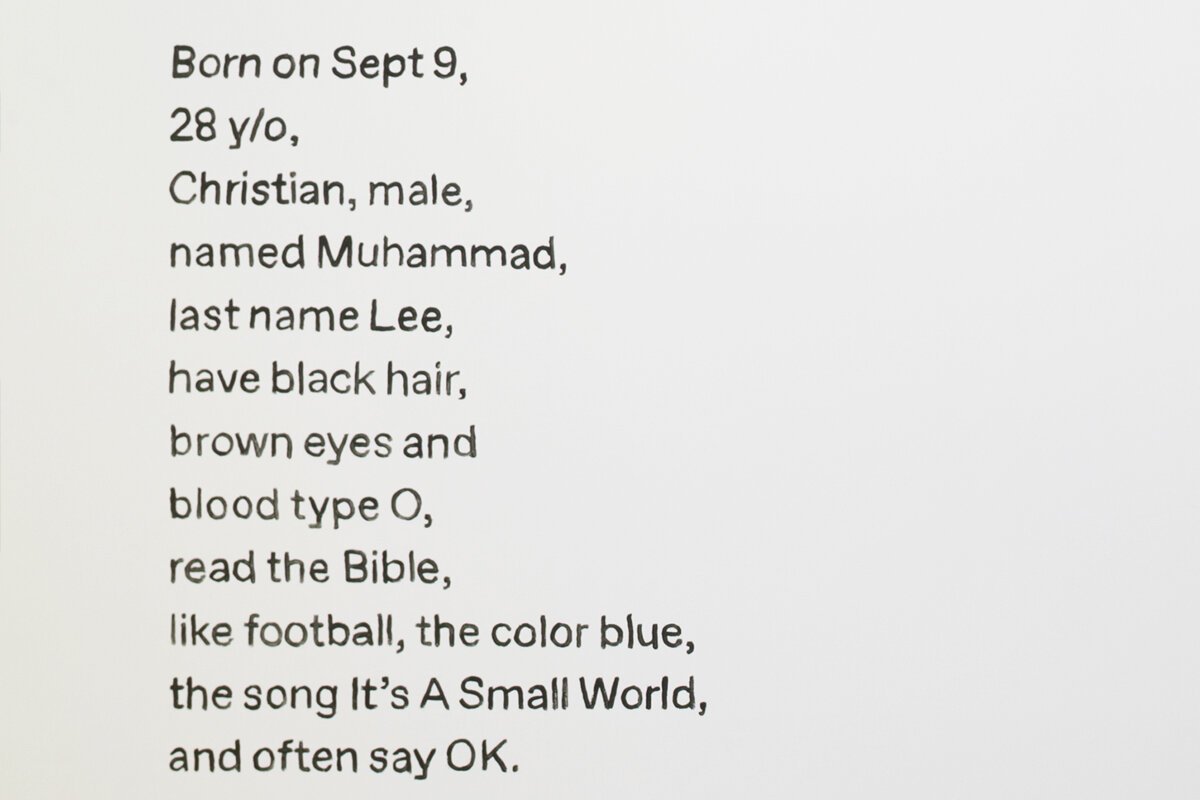

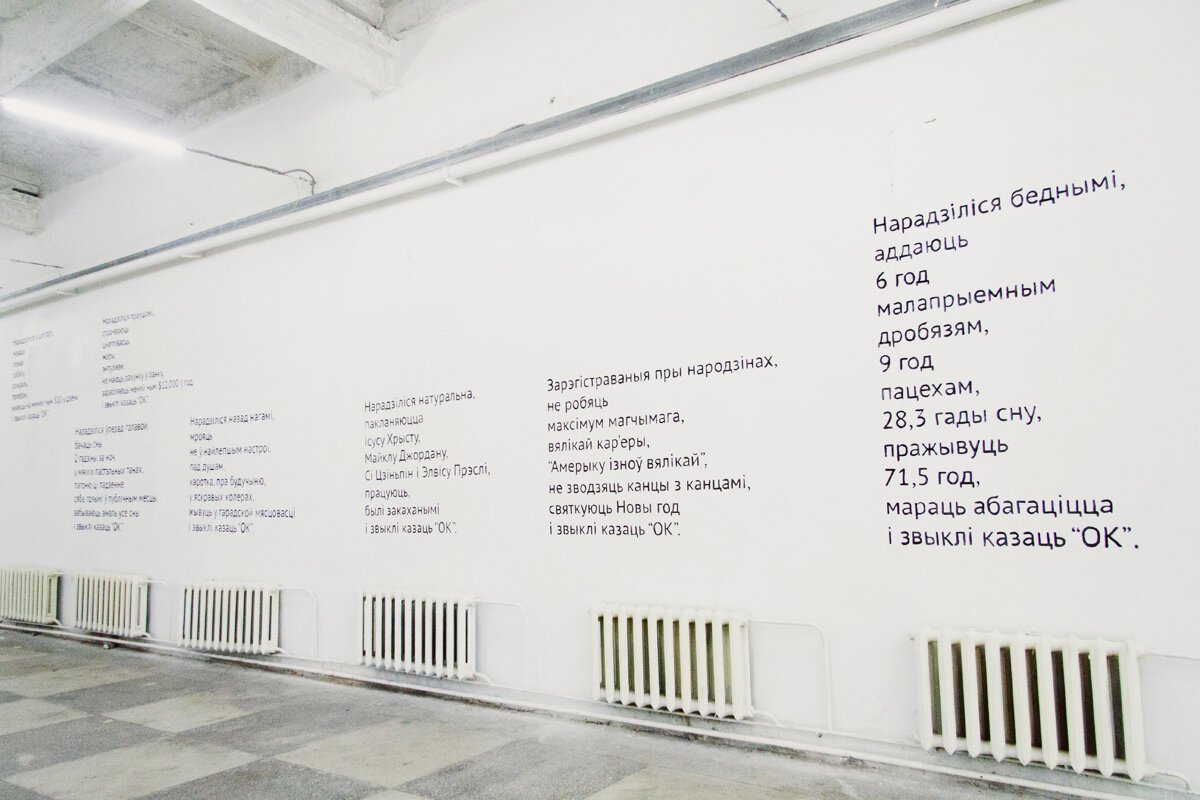

If the border is what you fight for and body what you fight with, then poetry in life is a tool for survival. The works within the Concrete Poems series depict a literal approach to a visual poetry tradition that takes on a specific typographic arrangement to convey meaning. Inspired by street wall scribbles, grafiti, and absurdist poetry, the artist makes her mark firmly in concrete. Breaking down words into a context that brings new meaning or finds irony in everyday language, Imagination Nation; Mother Other; Father Her; Slaughter Laughter. Bliumis exploration of her second language of English finds that even one letter can make all the difference.

The exhibition is accompanied by text written by art critic, media theorist, and philosopher, Boris Groys.

Boris Groys ART HISTORY OF VIOLENCE

We are accustomed to living in a disenchanted and designed world – the world of administration, technology, geographical maps, statistical data and abstract painting. In this world almost all wild forms of life are already domesticated and put under control: tigers and lions live in national parks or in zoos. However, there remains suspicion that some strange, alien forms of life are concealed under the familiar surfaces of our world and cannot be totally suppressed. In the polytheistic myths of ancient cultures the flows, woods and mountains became animated. And through this act of animation they became also dangerous and violent. In her art Alina Bliumis applies the same act of animation on the familiar images of our lifeless, soulless, administered world. As a result, the hidden energy of violence and aggression becomes revealed upon which those images owe their aura of tranquility and peaceful stability.

Indeed, when we look at the political map of the world, on which every country is presented by a certain geometrical form, we tend to forget that this form is always a result of bloody wars and oppression. In her series “Nation Unleashed” Alina reveals the “animal” energy of hate and aggression to which contemporary countries owe the shapes of their borders. She shows the peaceful surface of our world as camouflage concealing the violent fight for dominance. Of course, as an artist of Belorussian origin Alina cannot turn her eyes away from the eruptions of violence that currently take place in her region. However, long before these actual events took place, she was attentive to, what one can call, the political zoology of our contemporary world –the descent of national political symbols from mythical animals of the polytheistic past.

Alina’s disbelief in the surface characterizes her series “Bruises.” Images on their surface that look to be late examples of abstract expressionism become revealed as images that remain on human skin after a punch. Here again peaceful art for art’s sake suddenly turns into a document of physical violence and the fate of the body in the contemporary world. And in the series “Concrete Poems” familiar words that seem to be merely vehicles of ordinary communication begin to dissolve, revealing an abyss of the absurd hidden behind their grammatically correct surface.

Theodor Adorno famously said that to write poetry after Auschwitz is impossible. The appearance of the beautiful would only serve as cover making us forget the cruel reality of our world. Many artists reacted to this challenge by making their artworks look as ugly as reality itself. However, in this way they missed the cruelty of the second degree – the cruelty of the aestheticizing cover-up. It is this cruelty of the second degree – the cruelty inherent to the artistic practice itself – that Alina makes her topic in a subtle and at the same time surprisingly direct and convincing way.

*The exhibition Borders and Bruises at Anna Zorina Gallery, LA is accompanied by text written by art critic, media theorist, and philosopher, Boris Groys.

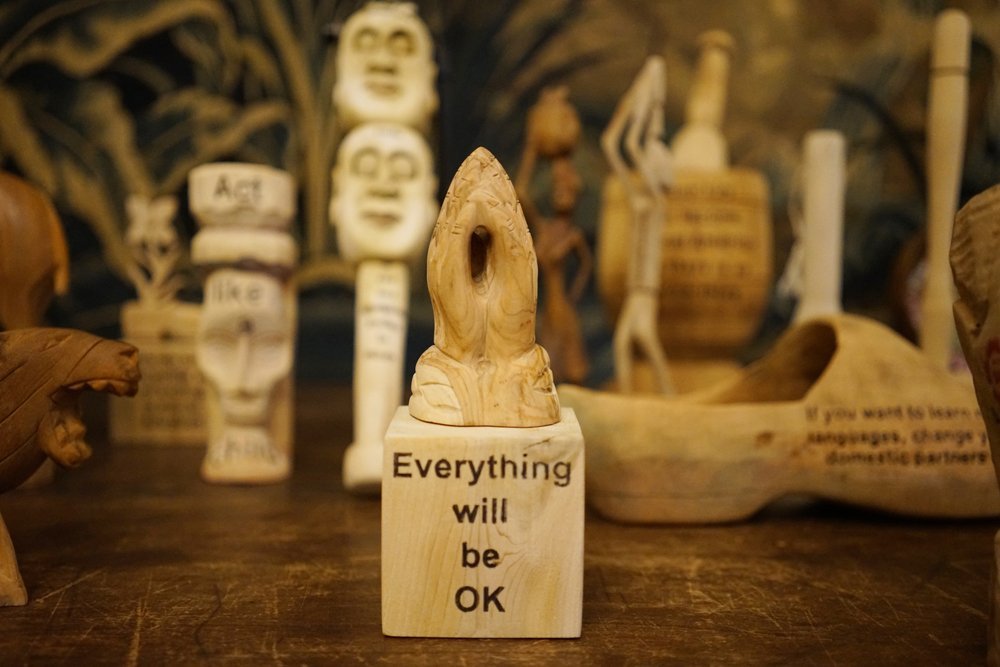

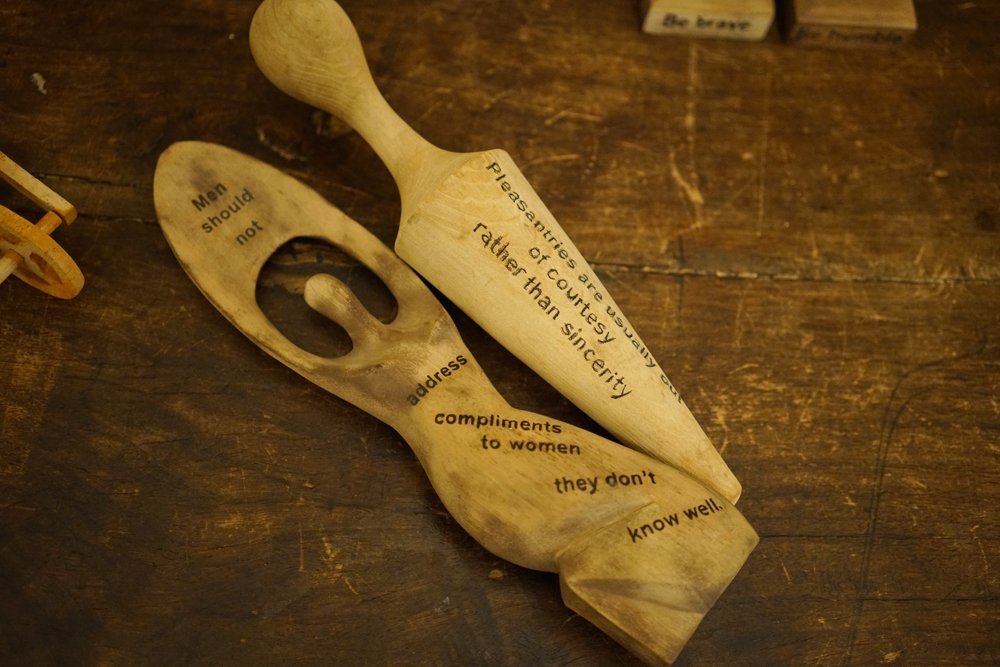

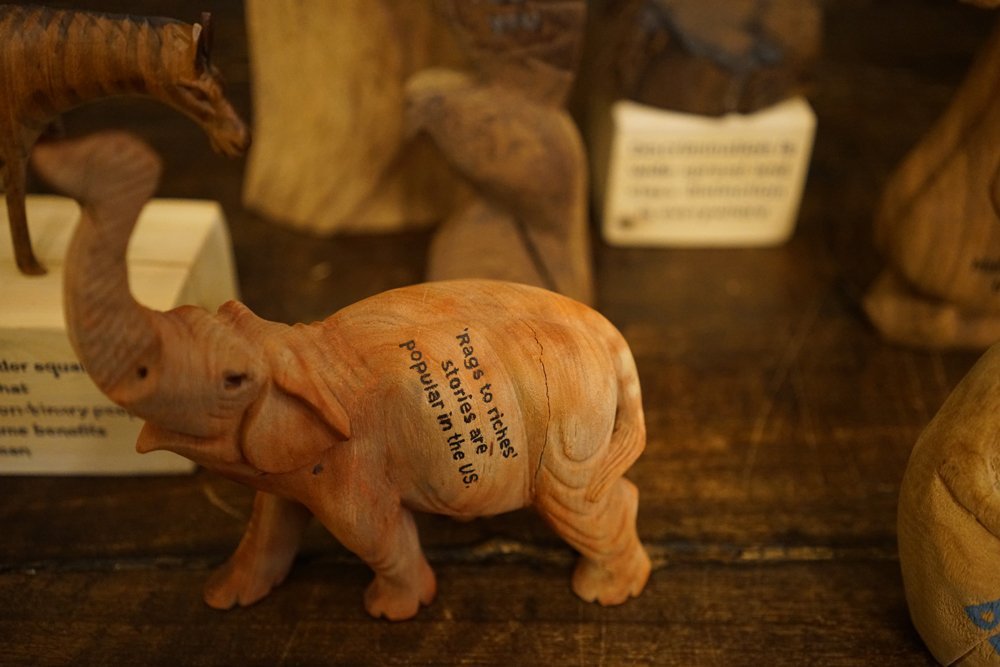

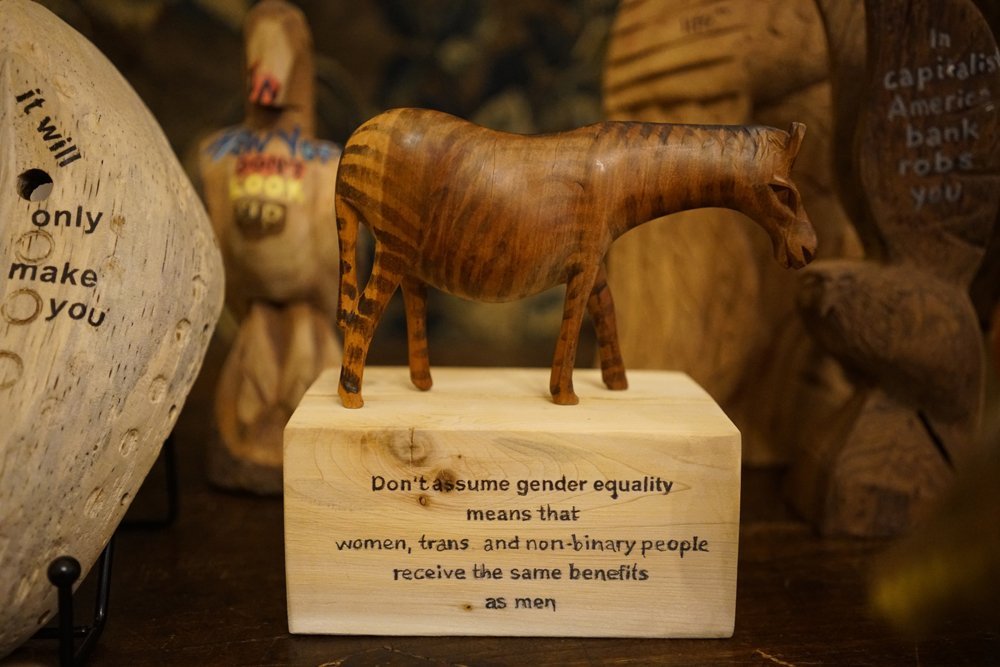

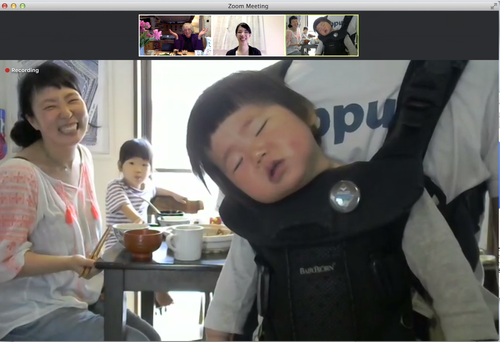

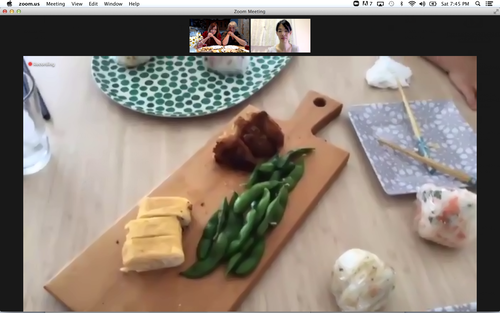

Alina and Jeff Bliumis CULTURAL TIPS FOR NEW AMERICANS Curated by Sozita Goudouna, Occupy Art Project, The French Consulate, NYC February 17 - March 9, 2022

Alina Bliumis, Jeff Bliumis

CULTURAL TIPS FOR NEW AMERICANS

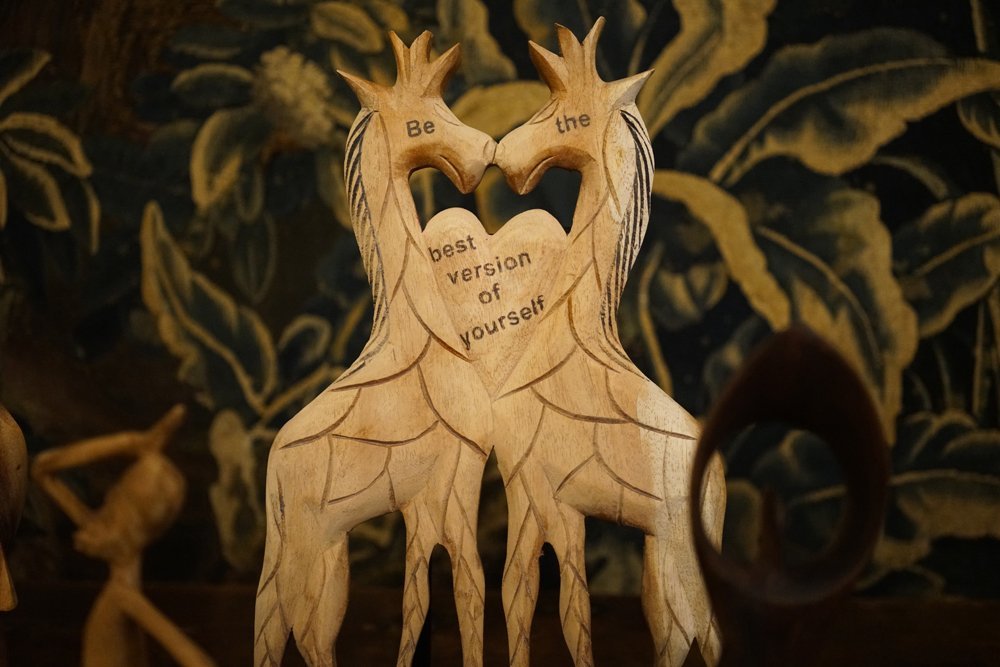

2022, 110 objects, wood and ink

For the last years, we have been gathering tips on “how can immigrants blend in the American society“ using street questionnaires, handbooks, social media and public forums. Concurrently, we collected ethnic wooden souvenirs, which radiate a certain fetishization of otherness, from all around New York City and sandblasted these objects to remove their original decorations and uncover the wood underneath. The cultural tips are then written onto the wooden souvenirs in ink, causing them to become decontextualized objects, much like the immigrants to whom the cultural tips are addressed.

Alina Bliumis, IMAGINATION NATION Elma, NY October 23 - November 30, 2021

“First, there is the old truth that ‘In the beginning is the body,’ with its desires, its powers, its manifold form of resistance to exploitation. As is often recognized, there is no social change, no cultural or political innovation that is not expressed through the body, no economic practice that is not applied to it.’”

— Silvia Federici “Beyond the Periphery of the Skin” 2020.